Paul Russell on Bernard Williams in TLS:

'Williams ends his study on a related (dark) note, concerning the lack of “harmony” in the world. The question we encounter when we consider the works of the ancient Greeks, he suggests, “is whether or not a given writer or philosophy believes that, beyond some things that human beings have themselves shaped, there is anything at all that is intrinsically shaped to human interests, in particular to human beings’ ethical interests”. Greek tragedy has no room for a world that supposes that, if we understood it correctly, we could learn how to be in harmony with it. With the collapse of the illusions that “morality” fosters, we are now well positioned to recognize that our ethical situation is much closer to that which is portrayed in the works of the Greek tragedians.

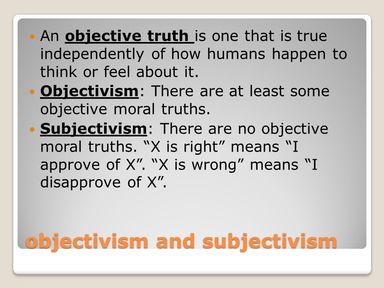

Do these conclusions leave us trapped in a world stripped of all optimism and without hope? Williams makes very clear in his closing remarks in Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy that this is not his view, and much of his later philosophical work is devoted to elaborating on this point. One vital source of hope still available to us is that of truth. In Truth and Truthfulness (2002) Williams employs a genealogical method to account for the value of truth by way of an account of the twin virtues of truthfulness: accuracy and sincerity. The immediate target of these reflections and observations are those “deniers”, like Richard Rorty, who question whether there can be such a thing as “objective truth” and what value it might have. Another source of hope available to us is to be found in politics. In his posthumous collection In the Beginning was the Deed (2008), which includes a number of his later papers, Williams seeks to show that, whatever the failures of the Enlightenment, there is no reason to abandon our respect or hopes for freedom and social justice. What these values and ideals do not need, however, are political philosophies that are simply extensions of moral theory applied to the realm of politics. In place of projects of this kind Williams suggests that we embrace a form of “political realism” as a way of thinking about and justifying our institutions and practices. An approach of this kind would place proper emphasis on the relevance of historical circumstances, the need for a credible understanding of human psychology, and, in particular, it would take “the first question” of politics to be about securing conditions of safety, trust and cooperation. Suffice it to say that Williams’s discussion of all these matters is even more pertinent in the present state of the world than it was when first written.

One particular danger when considering Williams’s thought is to approach his work on a piecemeal basis (practical reason/ moral luck/ utilitarianism/ etc). Viewed in that way, it comes across as haphazard and lacking direction. The truth, however, is the opposite: the individual contributions that Williams made all relate to his wider and more ambitious programme. Taken as a whole, Williams’s philosophical contribution is greater than the sum of its parts – a point that deserves some emphasis.

What, then, are we to say about Williams’s legacy? Perhaps the most powerful source of dissatisfaction with Williams’s philosophy is that he does not provide “good news” of any kind. Delivering good news, however, is not something that Williams is interested in, since it involves sacrificing philosophy’s commitment to the value of truth.'

Read the article here.

No good news. Whenever art or philosophy try to offer good news we have to be en garde. But hope can be found in truth and truthfulness: accuracy and sincerity. And the longing to be accurate and sincere doesn't need proof of objective truth.

That's enough for 2019: accuracy and sincerity, and playfulness in between.