Jacqueline Rose in LRB on counting, innocent murders, Camus, and the state:

“Counting is at once a scientific endeavour and a form of magical thinking. It can be a way of bracing ourselves for and confronting an onslaught, and at the same time a doomed attempt at omnipotence, a system for classifying the horror and bundling it away. What exactly are we being told each time the latest figures are announced, rising consistently, dropping slightly, increasing again? Other than that we cannot get a grip on what is happening. We take all the measures there are to be taken, adequate and inadequate according to where and who we are. And we wait.

In Camus’s novel, it is only when men start dying, as opposed to hundreds of rats, that the public begins to understand. And even then, only slowly. The announcement of 302 dead citizens in the third week of the epidemic does not speak to the public imagination: ‘The plague was unimaginable, or rather it was being imagined in the wrong way.’ As Camus had put it in his composition notebook of 1938, the people are ‘lacking in imagination ... They don’t think on the right scale for plagues. And the remedies they think up are barely suitable for a cold in the nose. They will die (develop).’ Perhaps, some people in the novel suggest, not all these deaths are attributable to the plague. What would be the average number of deaths in a week, they ask, for a city of this size in the normal run of things? These are the formulae, almost exactly, that were reached for by Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro in their earliest denial mode (from which Bolsonaro remains unbudged). To Camus, such thinking shouldn’t be dismissed as the ranting of dangerous fools, even when it is that. He is interested in how human subjects deal with disaster. Denial, or defence, is integral to how the mind behaves under pressure. Wars and plagues are met with disbelief. It is inconceivable that they are happening at all, or that, given their affront to human dignity – their ‘stupidity’, to use Camus’s word – they will endure: ‘There have been as many plagues as wars in history, yet always wars and plagues take people equally by surprise’; ‘It was only as time passed, and the steady rise in the death rate could not be ignored, that public opinion came alive to the truth.’

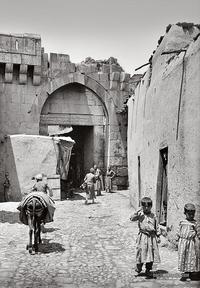

And yet, for Camus, refusing to submit to indiscriminate numerical calculations also represents a form of creativity, a decision to imagine the world beyond the agonies of the hour. Doing otherwise risks replicating the merciless logic of the plague itself. The first real sign in the novel that the disease might be nearing its end comes when the numbers no longer add up or make sense: rising deaths on Mondays, while on Wednesdays, for some reason, hardly any at all; hundreds still dying in one district, other places where the plague seems to have quietly slipped away. The plague, Camus’s narrator remarks, was losing ‘its self-command, the ruthless almost mathematical efficiency that had been its trump card hitherto’. Mathematics flattens. It is a killing art. Counting humans, alive or dead, means you have entered a world of abstraction, the first sign that things have taken a desperate turn. Of course counting can also mean the exact opposite. If someone counts, they matter, with the further implication that they can be held answerable for their own deeds. Not to count, on the other hand, is to be overlooked or invisible, like the Arabs of Oran, whose virtual absence from Camus’s portrayal of the French Algerian town where the novel is set seems now to be its most significant failing; more than a hundred thousand were living in Oran at the time.

‘Counting’ might, then, be an example of what Freud called the ‘antithetical meaning of primal words’ characteristic of the most ancient Egyptian languages: words which simultaneously denote one thing and its opposite, and which also possess a kind of magic, since they release you into a world of contradiction and mystery. To use such words is always to take a risk. The meaning you least intend lies just below the surface, like the plague which, even after it has abated, Camus insists, has never gone away.”

(…)

“Today, the insistence is that ‘we’ are all in this together, even as social disparity – the frailty of that ‘we’ – has never been so obvious: in the gulf that exists between families with gardens and those housed in airless, cladded tower blocks, a distinction disregarded by police rounding on people in parks; between the jogging culture of North London and the slums of Bangladesh, where the idea of social distancing, let alone of soap and hand sanitisers in abundance, is a sick joke; between the medical care given to the prime minister, assigned an ICU bed at a time of acute shortage while still fit enough – or so we were initially told – to govern, and the negligence suffered by Thomas Harvey, a nurse from East London who had worked in the NHS for twenty years, whose family were advised he didn’t need to go to a hospital (they called four times) before he died gasping for air in his bathroom.

Oddly, the panic-buying provoked by Covid-19 has served to detract attention from the more basic problem of maintaining the food supply in times of pestilence and war. Focusing on individual greed, which has been the response in the UK (‘Buy less!’ or ‘Only take your fair share!’), implies that, if only people restrained themselves, everyone would still be living in a world of plenty. Stories of robberies and attacks on supermarkets in the poorest areas of Southern Italy – where people face a real risk of starvation – barely make it into the news in the UK, suggesting that the only deaths worth reporting are those that are a direct result of the pandemic. As if nobody was dying before. This isn’t unusual. Writing in the middle of the First World War, Freud noted the tendency to treat all deaths as woeful exceptions rather than something we all get round to in time. When the issue of supply is raised, it tends to be part of a discussion – a necessary one – about the possibly irreparable damage done to the food chain by globalisation. No one yet knows whether the world after Covid-19 will be more attuned to climate change, and will take the appropriate measures to respond to it, or if the exploitation of natural resources will accelerate to make up for lost time.”

(…)

“For many contemporary critics, Camus’s cry for justice, and even insurrection, did not go far enough. By the time The Plague was published, he had moved a long way from the 1930s, when he was expelled from the French Communist Party over his support for the founder of the Algerian Popular Party, Messali Hadj. Hadj had struggled for national liberation – though not immediate independence – and was deported from Algeria as a dangerous agitator following nationwide labour strikes and demonstrations. At that point, the PCF saw Camus as privileging the anti-colonial struggle over the class war. It is ironic (Jeremy Harding discussed the irony in the LRB of 4 December 2014) that Camus should now be seen as letting down the Arab cause, having been such an astute critic of colonialism and in terms ahead of his time: he saw the ‘institutional’ injustice; the repeated ‘lie’ of assimilation; the manifest unfairness of land and income distribution; the ‘psychological suffering’ and damage caused by the ‘contempt’ of the coloniser towards the colonised. But, in the end, Camus would not be forgiven for failing to back full Algerian independence. From Sartre’s point of view, in their famous falling-out, Camus’s later turn against Soviet Communism was also a fatal error, a gift to the wrong side in the Cold War and a betrayal of the struggle against US imperialism in Vietnam.”

(…)

“In the course of a public conversation with me ten years ago, Juliet Mitchell stated, to my complete surprise and that of our discussant, Jean Radford, that modern-day feminism, despite its setbacks and failings, had been an unqualified success. Because, she explained, feminism will always be ‘the longest revolution’, the one you never give up on even in the knowledge that it is unlikely ever to come to an end. When I read about the women whose only option today is to be trapped in their homes with an abusive partner, I find it hard to share Juliet’s spirit. Except in so far as this virus, like Camus’s plague, is making us newly alert to and responsible for the worst of what we see.”

(…)

‘For Tarrou, murder is state murder. His most disturbing childhood memory is of watching in a courtroom as his father, a prosecuting attorney, condemned a man to death (‘His head must fall’). The convict was clearly guilty and horrified at what he had done. He looked like a ‘yellow owl blinded by too much light’, tie awry, head swivelling in despair. Up to that moment Tarrou had believed in his own innocence as a man, but he realised then that to be a citizen subject is to be involved in sanctioned murder every day. No one is exempt or indemnified (‘indemne’). Even those who are better than the rest, he explains, cannot prevent themselves from killing or letting others kill: ‘Such is the logic by which they live and we can’t stir a finger in this world without bringing the risk of death to somebody.’ Alienated from his father – without telling him why – he becomes an activist for the abolition of the death penalty, but this fails to assuage his guilt. The plague comes as no surprise: ‘I had plague already,’ he opens his monologue, ‘long before I knew this town and this epidemic.’ He is a carrier (‘un pestiféré’), liable to infect others at every turn: ‘Each of us has the plague within him; no one, no one on earth is free from it. And I know too that we must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection on him.’ Tarrou has taken the principle of social distancing and run it into the epicentre of state power.”

(…)

“The proposition that we are all killers collides with ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill,’ perhaps the fiercest of the commandments. Tarrou is therefore very far from intoning that ‘we are all miserable sinners,’ the soft, handwringing lament he has already dispatched in his exchange with Father Paneloux. Nor is he scrambling key distinctions, in the way the novel as a whole was accused of doing. He is not conflating resisters and collaborators – Cottard is ‘an accomplice’ who is also in flight from some hidden past crime; Grand is a hero – or the powerful and destitute: all his sympathies are with the ‘owl’ in the dock, whatever his crime may have been. Rather he is pointing the finger at the modern state, which forbids violence to its citizens, not because, as Freud puts it, ‘it desires to abolish it, but because it desires to monopolise it, like salt and tobacco’. For Tarrou, the responsibility of the citizen for his own violence is not diminished by such fraudulence but intensified, since it confronts him with what the state enacts in his name. The plague will continue to crawl out of the woodwork – out of bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs and old papers – as long as human subjects do not question the cruelty and injustice of their social arrangements. We are all accountable for the ills of the world. Tarrou aspires to be an ‘innocent murderer’ (even at one point to be a saint), by which he means one who recognises the plague as his problem and fights against it with every breath he takes. On the last page, the narrator tells his readers that he wrote the story so as to leave behind a memory of the injustice and violence undergone, and in order to state ‘quite simply what we learn in a time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise’. There is still everything to play for. A thought for the aftermath, when there will be so much to be done.”

Read the complete article here.

The raison d’être of the state (I’m not sure why the adjective “modern” is added in the paragraph above) is the monopoly of violence. How the state is using this monopoly is its litmus test. Most states fail.

If we all have the plague within us, the plague must a metaphor, and I’m not sure how far this metaphor is from the Christian idea of the original sin.

In that case the state would be both the original sin and the answer to this sin.

What does it mean to be an innocent murderer? If we can imagine the murderer being innocent then we can also imagine Sisyphus being happy.

Maybe just because of this: there are more things to admire in men than to despise.