On a different sort of death sentence – Katy Waldman in The New Yorker:

‘The Calvino of “Crossed Destinies” is a familiar one, the magical realist with a playful approach to the author-narrator-reader relationship. But the book also captures one of his spinier qualities: his aura of danger. He likes to pry things open, often in uncomfortable ways; “Crossed Destinies” throws together characters who can communicate only through tarot cards, and ends when the deck scatters, along with their identities. This is formal violence, the story flying apart like a tossed hand, but a bodily analogue is never far away: one man describes being dismembered, how “sharp blades . . . tore him to pieces.” And yet, because much of Calvino’s cruelty is abstracted, it seems free of malice, which makes it all the more magnetic. Even before they disintegrate, the characters in “Crossed Destinies” are subject to bizarre structural rigors: pulled from the forest, stripped of their voices, severed from their pasts. When brutality occurs at the level of form, flashing in every choice (or “renunciation”), it can surface how narrative is not just an act of creation but—for the unseen, unwritten alternative—a death sentence.’

(…)

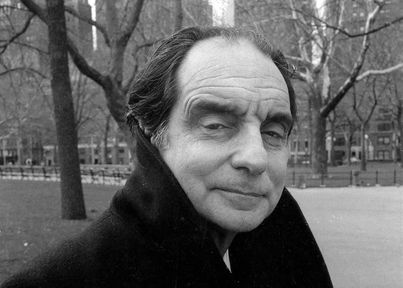

‘Calvino’s own raven came in 1985. Since then, he has acquired the veneer of cultish allure that I associate with authors—David Foster Wallace, John Kennedy Toole, J. D. Salinger—who are frequently name-checked on Reddit. He is clever and protean, and his metafiction has a galaxy-brain swagger. (The novel “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler” begins ten times; its fragments are bound by a frame featuring You, the Reader, as well as an enchanting Other Reader named Ludmilla.) But Calvino’s work, which concerns the romance and frustration of the inexpressible, rarely feels gimmicky; it affords too much respect to the void.’

(…)

‘Calvino’s early biography, which plays a role in his mythos, may be relevant here. He grew up affluent on a working farm in San Remo, surrounded by the area’s thick woods and by the avocados and grapefruits that his father, an experimental agronomist, improbably grew. Calvino’s parents were exacting, emotionally reserved, and politically committed. After Germany invaded, in 1943, he joined the Italian Resistance; he fought for more than a year with the Garibaldi Brigade while the Nazis held his parents hostage. (They were later released.) When the war ended, Calvino settled in Turin, where he threw himself into the workers’ movement and began publishing short fiction. Giulio Einaudi, the influential publisher, smoothed Calvino’s introduction to members of the intellectual left, including Natalia Ginzburg and Cesare Pavese, who would become a close friend and mentor. As a novelist, Calvino initially practiced neorealism. In 1954, though, Einaudi gave him an assignment: gather folktales and fairy tales from across Italy, translate them from their native dialects, and convene them in a single volume. The Grimm-like project was an education in the building blocks of stories, in their uncanny, recombinatory power.’

(…)

‘ Instead of awe, the reader of “Last Comes the Raven” registers a bloom of social feelings: sympathy, recognition, curiosity. When a character is cruel, she possesses a motivation. When she suffers, historical circumstances can help illuminate her pain. The book’s particular milieu—neighborhoods that have been scarred by the Italian civil war of the mid-twentieth century—may already be familiar to many American readers, thanks to the Neapolitan quartet, a series of blockbuster novels by the writer Elena Ferrante. (Ferrante’s translator, Ann Goldstein, is one of five to render these Calvino stories into English.) “My Brilliant Friend,” the first of the novels, was striking for how it mapped changes in its young characters’ thinking: Lenù, the narrator, initially understands her world as a child might, via ogres and enchanted shoes; only later does she connect the violence she senses with her city’s political past. Calvino’s work moves in the opposite direction, away from temporal or geographical coördinates and toward the elemental gloom of fairy tales. Was he flinching from trauma, one wonders, or sublimating it? Then again, why choose?’

Read the article here.

So why exactly should the narrative be a death sentence? It condemns to death every detail that the narrator didn’t deem worthy of mentioning.

What we don’t remember might be the most important thing to remember. If that’s the case, then we could say: what we don’t tell is the most important part of the narrative. What’s left out is the core of the story, what we readers don’t know, yet we are able to assume a thing or two, our suspicions, that’s what’s storytelling (the novel) is all about.