On Céline once more - Damian Catani in TLS:

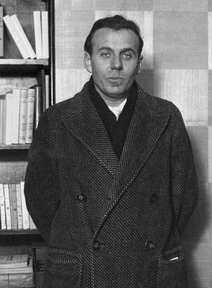

‘Louis-Ferdinand Céline is regarded by many as the most important twentieth-century French novelist. He is celebrated for the innovative “oral” style of his written prose and his unflinchingly honest first-person narrative voice, marked by a coruscating black humour. His powerful, visceral depictions of war and social oppression are unlike anything else in modern or contemporary writing. Céline’s debut novel, Voyage au bout de la nuit (1932; Journey to the End of the Night, 1934), catapulted him to international fame. Only a few years later, between 1937 and 1941, he irrevocably damaged his reputation by publishing three antisemitic pamphlets. As a Nazi sympathizer he was forced to flee to Denmark via Germany in 1944, but was pardoned by the French government in 1951, achieving partial rehabilitation through his publication of the so-called German trilogy of novels, D’un château l’autre (Castle to Castle), Nord (North) and Rigodon (Rigadoon), between 1957 and 1961. Yet Céline has never fully shaken off the stigma of his antisemitism and fascist associations. In 2017 this “dark side” came under renewed scrutiny when Gallimard controversially announced plans to reissue his pamphlets, before eventually backtracking. While entirely understandable, the outrage risked completely overshadowing Céline’s colossal achievements as a writer of fiction.’

(…)

‘In this wayLondres quietly nods to the nineteenth-century French realist novel of prostitution, notably Balzac’s Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes (1847; A Harlot High and Low) and Zola’s Nana (1880). But Céline makes the genre his own. Nana, for example, rises from streetwalker to high-class courtesan by exploiting her male clients in the corridors of power. By contrast, Ferdinand and his motley crew live hand to mouth in an economically deprived wartime London. The brothel profits from a stream of sex-starved soldiers on leave, but also must reckon with an attentive police force, rendering the trafficking of women from abroad to work as prostitutes incredibly precarious. War breeds paranoia, even in London, far from the front line. Not only do zeppelin attacks incinerate buildings, but demobbed soldiers and their loved ones are terrified that they will be sent back to the front. The capital is flooded with draft-dodgers, deserters and illegal immigrants, not to mention the police informants and spies whose job it is to catch them. Ferdinand and his gang have to carefully plot their way around the city, often taking enormous detours to avoid being followed by undercover police or reported by snitches, invariably disgruntled former prostitutes, rival pimps or opportunistic citizens looking to make a quick couple of quid. Nobody can be trusted; loyalty is scarce and betrayal rife.’

(…)

‘Although Céline spent just over a year in the British capital recuperating from the war injuries he suffered in 1914, details of his stay there, especially the last five months, remain hazy. We know he first worked in the passport office of the French consul on Bedford Square, that he lived at 71 Gower Street and 4 Leicester Street in Soho, that he married a young French dancer and nightclub employee named Suzanne Nebout, and that this was probably a marriage of convenience to secure residency at a time when foreigners in the UK were viewed with suspicion. Indeed, Céline wasn’t above all suspicion: he would later cryptically recall that “J’avais tout pour être proxénète” (“I had everything to be a pimp”). More likely, he gleaned much of his knowledge of London’s French prostitution rings in the 1920s and early 1930s from his friends Joseph Garcin and Jean Cive, both of whom had close links with the milieu.

It is also probable that Céline’s reading of Freud at this time fuelled his imagination as much as his real-life experiences. He was familiar with Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) and the psychoanalyst’s notions of the sex drive and the death drive. Accordingly, violence and the libido are unleashed in Londres as uncontrollable forces that cannot be restricted to the spaces that are meant to contain them: the military zone of the trenches or behind the closed doors of the brothel. Following Freud, Céline depicts Eros as the life-affirming force that seeks to assert itself over Thanatos, the death instinct.’

(…)

‘

Louis-Ferdinand Céline is regarded by many as the most important twentieth-century French novelist. He is celebrated for the innovative “oral” style of his written prose and his unflinchingly honest first-person narrative voice, marked by a coruscating black humour. His powerful, visceral depictions of war and social oppression are unlike anything else in modern or contemporary writing. Céline’s debut novel, Voyage au bout de la nuit (1932; Journey to the End of the Night, 1934), catapulted him to international fame. Only a few years later, between 1937 and 1941, he irrevocably damaged his reputation by publishing three antisemitic pamphlets. As a Nazi sympathizer he was forced to flee to Denmark via Germany in 1944, but was pardoned by the French government in 1951, achieving partial rehabilitation through his publication of the so-called German trilogy of novels, D’un château l’autre (Castle to Castle), Nord (North) and Rigodon (Rigadoon), between 1957 and 1961. Yet Céline has never fully shaken off the stigma of his antisemitism and fascist associations. In 2017 this “dark side” came under renewed scrutiny when Gallimard controversially announced plans to reissue his pamphlets, before eventually backtracking. While entirely understandable, the outrage risked completely overshadowing Céline’s colossal achievements as a writer of fiction.

His place in French literary history again rose to the fore in August 2021, when Le Monde revealed that a chest containing 6,000 unpublished pages of Céline’s manuscripts had been discovered. The news was unexpected and the pages included an unedited version of the novel Casse-Pipe; a medieval legend (La Volonté du roi Krogold); an early draft of his 1936 novel Mort à crédit (Death on Credit); a short, untitled novel; and a three-part novel entitled Londres.

These manuscripts were handed to Céline’s executors by the former Libérationjournalist Jean-Pierre Thibaudat. In Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Le trésor retrouvé, Thibaudat gives his side of the story, one mired in the chaos of post-liberation Paris. His involvement stretches back to April 1982, when he met Caroline Lanciano-Morandat, daughter of Yvon Morandat, a prominent left-wing resistant and a key member of General de Gaulle’s Free French forces. Morandat had moved into Céline’s Montmartre flat at 4 Rue Girardon shortly after the author fled Paris for Germany. Thibaudat claims that Morandat took possession of the manuscripts, and not, as many Céline scholars have claimed, Oscar Rosembly, a Corsican collaborator turned resistant. Apparently, Morandat’s daughter accidentally stumbled upon the box of manuscripts years later, in her basement, and felt that Thibaudat, with his left-leaning literary credentials, could be entrusted with their safekeeping. They agreed that he would not hand them over to Céline’s widow, Lucette Destouches, for fear that she would withhold, edit or hide certain portions of the manuscripts as a way of managing her late husband’s legacy. Thibaudat promised to wait until Lucette’s death before making this discovery public. He had to wait until November 2019, when Lucette finally died at the age of 107, fifty-eight years after Céline’s death.

Céline’s executors, François Gibault and Véronique Chovin, argued that they had illegally and needlessly been deprived of this treasure trove for decades, and took legal action against Thibaudat. Thibaudat, having honoured the donor’s wishes and spent countless hours deciphering the manuscripts, felt equally miffed at being cut out of the picture and denied a say in how they would be disseminated. He wanted them to be donated to reputable public archives: either the Bibliothèque nationale or the Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine. Gibault and Chovin disagreed, and won out. With the fervent backing of Céline scholars including Pascal Fouché and Henri Godard, they authorized Gallimard to publish the untitled novel as Guerre along with Londres in 2022, with La Volonté de roi Krogold scheduled for publication this April. All of the newly discovered books are set to be consecrated this May by being published in a two-volume appendix to Gallimard’s Pléaide edition of Céline’s complete works.

As well as the thorny issue of intellectual property, the manuscripts of Guerre andLondres pose a fascinating challenge for scholars of Céline. How should we measure their literary value? Should we read an early draft of a Céline novel in the same way as the better-known books published during his lifetime? Did Gallimard unfairly rush to capitalize on the excitement of the manuscript discovery by publishing Guerre and Londres as standalone novels? Céline was a notoriously meticulous writer who endlessly pored over successive drafts before he was ready to publish. His original publisher and editor, Robert Denoël, was no less uncompromising when it came to excising passages that he considered too racy. This is precisely what he did with Mort à crédit, which led to a rare falling-out between the two men. How a version of Londres seen through to publication by its author would have looked is open to conjecture, nor can we even be certain that Céline would have wanted to finish the book.

Nevertheless, at more than 500 pages, even this unfinished version of Londres is a significant addition to Céline’s overall body of work in its gripping storytelling and compelling evocations of time and place. In a letter of July 14, 1934 to the author Eugène Dabit, he envisaged it as part of a triptych – Enfance, Guerre, Londres(Childhood, War, London). Régis Tettamanzi, who edited the Gallimard Londres, suggests that Enfance directly relates to Mort à crédit, published in 1936, but that Londres was written in 1934 and refers to Céline’s stay in London in 1915–16, after his demobilization. The story, which follows on from Guerre, centres on a group of pimps, led by Cantaloup, a charismatic and streetwise Frenchman who rules his Soho brothel – the “Leicester Pension” – with a rod of iron. The novel is narrated by Cantaloup’s friend and associate Ferdinand, the same first-person narrator as Ferdinand Bardamu, Céline’s memorable antihero and semi-autobiographical alter ego in Voyage au bout de la nuit. Guerre charts the traumatic aftermath of Bardamu’s war injuries, his sexually active convalescence with a hospital nurse and his infatuation with Angèle, a fickle prostitute and widow of the pimp Cascade, for whose death she is responsible. When she lands herself an English protector, the married, middle-aged Major Cecil B. Purcell, Angèle and Ferdinand immediately seize the opportunity to join him in London. In Londres, Angèle becomes a kept woman, enjoying the plush surroundings of Purcell’s luxurious Maida Vale bachelor pad.

A novel entitled Londres immediately invites comparison with Guignol’s Band, Céline’s euphoric two-volume 1944 love letter to the British capital. Despite the broad similarities – a handful of recurring characters, both set in London during the First World War – there are key thematic and stylistic differences that reflect contrasting periods in Céline’s life. Guignol’s Band seeks to escape reality: it was written as an antidote to the extreme anxiety the author felt at having to flee France. Germany was facing defeat and he was a marked man because of his fascist sympathies. Poetic, fantastical, dreamlike, upbeat and deliberately vague on historical and geographical detail, this is the nearest Céline comes to writing a magical realist work. Its nostalgic and light-hearted tone is joined by slapstick comedy and frequent references to Shakespeare, his favourite author. By contrast, Londres, written at a more settled time in Céline’s life, when his literary stock was still high, confronts gritty reality head on.

In this wayLondres quietly nods to the nineteenth-century French realist novel of prostitution, notably Balzac’s Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes (1847; A Harlot High and Low) and Zola’s Nana (1880). But Céline makes the genre his own. Nana, for example, rises from streetwalker to high-class courtesan by exploiting her male clients in the corridors of power. By contrast, Ferdinand and his motley crew live hand to mouth in an economically deprived wartime London. The brothel profits from a stream of sex-starved soldiers on leave, but also must reckon with an attentive police force, rendering the trafficking of women from abroad to work as prostitutes incredibly precarious. War breeds paranoia, even in London, far from the front line. Not only do zeppelin attacks incinerate buildings, but demobbed soldiers and their loved ones are terrified that they will be sent back to the front. The capital is flooded with draft-dodgers, deserters and illegal immigrants, not to mention the police informants and spies whose job it is to catch them. Ferdinand and his gang have to carefully plot their way around the city, often taking enormous detours to avoid being followed by undercover police or reported by snitches, invariably disgruntled former prostitutes, rival pimps or opportunistic citizens looking to make a quick couple of quid. Nobody can be trusted; loyalty is scarce and betrayal rife.

With its gritty depiction of urban space, Londres is to London what Mort à crédit is to Paris. Céline’s narrator whisks his reader around every nook and cranny of the capital – from Chelsea to Mile End Road, Maida Vale to Greenwich – but he does so with an eye for illicit activity rather than the petit-bourgeois respectability of Ferdinand’s shopkeeper parents. Economic survival is no respecter of moral hierarchy: brothels need to break even, just as lace shops do. Both novels fan outwards in concentric circles from a central hub of commercial activity and popular culture: London’s Soho and the Opéra district in Paris. There is, however, a crucial difference: the autobiographical elements in Mort à credit are much more recognizable than those in Londres. Although Céline spent just over a year in the British capital recuperating from the war injuries he suffered in 1914, details of his stay there, especially the last five months, remain hazy. We know he first worked in the passport office of the French consul on Bedford Square, that he lived at 71 Gower Street and 4 Leicester Street in Soho, that he married a young French dancer and nightclub employee named Suzanne Nebout, and that this was probably a marriage of convenience to secure residency at a time when foreigners in the UK were viewed with suspicion. Indeed, Céline wasn’t above all suspicion: he would later cryptically recall that “J’avais tout pour être proxénète” (“I had everything to be a pimp”). More likely, he gleaned much of his knowledge of London’s French prostitution rings in the 1920s and early 1930s from his friends Joseph Garcin and Jean Cive, both of whom had close links with the milieu.

It is also probable that Céline’s reading of Freud at this time fuelled his imagination as much as his real-life experiences. He was familiar with Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) and the psychoanalyst’s notions of the sex drive and the death drive. Accordingly, violence and the libido are unleashed in Londres as uncontrollable forces that cannot be restricted to the spaces that are meant to contain them: the military zone of the trenches or behind the closed doors of the brothel. Following Freud, Céline depicts Eros as the life-affirming force that seeks to assert itself over Thanatos, the death instinct.

In Londres, however, Eros is constantly fighting a rearguard action. The violence keeps recurring: characters desperate to lose themselves in sex to forget the war are repeatedly reminded of it by their own traumas. Ferdinand tries to enjoy the performance of the voluptuous dancers on stage at the Empire theatre, only to be seized by the fear of being sent back to the Western Front. Extravagant champagne and drug-fuelled orgies – both gay and straight attempts to blot out the horrors of the battlefield – are regularly organized by Lawrence Gift, the dissolute aristocrat who keeps a permanent suite at the Savoy. These orgies are, alas, only a limited success: Gift’s debauched gatherings provide just one more opportunity for arms dealers and war profiteers to do business.

At times war destroys the libido altogether, or twists it in strange directions. Before departing for the front Major Purcell cannot take his hands off the sexually insatiable Angèle, and indulges his voyeuristic fantasy of watching her having sex with Ferdinand. On his return this impulse has vanished, only to be replaced by a fetishistic obsession with gas masks, which he is keen to manufacture in his Willesden Green factory. Any humour here is dark and twisted: Ferdinand and Angèle urge Purcell to make love to her younger sister, Sophie, while he wears his latest mask; later, Ferdinand gleefully describes the different shades of colour Purcell’s skin takes on when he accidentally poisons himself while testing his mask’s effectiveness. Even the novel’s most comical character, Boro, the barrel-chested, piano-playing Russian anarchist, generates most of his laughs through an explosive cocktail of sex and violence. He writhes in agony in the middle of an orgy in the Leicester Pension, to which a dentist is implausibly summoned to extract his abscessed tooth. Later he challenges a seasoned boxer to a fight in the basement of the Crokett [sic], a seedy riverside pub where the cynical female Belgian proprietor promotes clandestine bare knuckle fights. The bizarre episode culminates in Boro fighting a real-life bear, which falls on top of him and defecates on his face.

If this macho posturing treads a fine line between outlandish humour and bad taste, there is nothing funny about the scenes of violence inflicted on women. The pimps think nothing of beating up the prostitutes if they are deemed to have stepped out of line. One Corsican pimp, Tresore, cuts off the fingers of “his” girls if they are disloyal or bring in insufficient funds. Ruthless economic exploitation morphs into irrationally violent possessiveness, and woe betide any prostitute who tries to run away. After getting pregnant by a married policeman, with whom she had hoped to start a new life, “La Joconde” – named after the Mona Lisa – is forced to conceal her pregnancy bump and get back onto the streets. So eager is the policeman to get rid of her, he allows Tresore to beat him up, gives him a blowjob and pays him twenty pounds, all on the condition that the brothel agrees to take her back. Nonetheless, it is the women who almost always come off worse, and it is hard to make a case for misogynistic and degrading scenes on the grounds of Céline’s hard-hitting social realism. It is difficult to imagine Robert Denoël letting such graphic descriptions through to a final draft.’

(…)

‘More surprising still, is that he is introduced to this world by a Jewish character, Dr Athanase Yugenbitz. Of all the male charactersYugenbitz is by far the most decent and socially respectable. He nurses one badly beaten-up character back to health and generously hosts Ferdinand and an incorrigible Boro for several months, alongside his family in his dingy flat, while they lie low avoiding the police. If this character owes something to the racist stereotype of the “Wandering Jew”, this is oddly positive: his complicated, peripatetic past means that he does not pry into Ferdinand’s life, let alone judge him. Indeed, so non-judgemental is he that he actively encourages Ferdinand’s interest in medicine: he lends him medical books, introduces him to his clients as his assistant and even allows him to tend to patients on his behalf. Ferdinand is moved beyond words. He is one of society’s underdogs, and no one has ever shown such faith in him: “C’est la première fois que ça m’arrivait. J’y croyais à peine” (“This was the first time this happened to me. I could hardly believe it”).

Of course, one positive Jewish character in the midst of his oeuvre does not suddenly exonerate Céline from the terrible antisemitism of his pamphlets. What it does do, however, is strengthen the argument, long made by many Céline scholars, that the antisemitism is exclusively a feature of the pamphlets, rather than of his fiction.’

(…)

‘Moreover, this novel is a real treat for lovers of “argot”, thereby anticipating the smorgasbord of slang that is to be found in Mort à crédit. Perhaps revealingly, there are more than half a dozen words for prostitute alone: colis, gagneuse, lot, marle, ménesse, môme, morue, poule and tapin.’

Read the article here.

This is quite another take on Céline than Alice Kaplan’s in NYRB, about a year ago. See here.

Kaplan’s hesitations were absolutely reasonable. But it’s tempting to believe that Céline’s fiction can be separated from his pamphlets.

What to do with the misogyny is a different question. I would say, accept it. The reader is an intelligent human being, wise enough to withstand fatal and less fatal attractions, as so far as misogyny is an attraction.

What the reader in Dutch or English or German will make of the argot synonyms for sex worker is a different question. At least is this an open invitation for another congress about literary translation. We can invite A.I. as well.

And then Freud, Céline as a Freud reader. Now that’s new to me.