On essentialism and Jewishness – Leora Batnitzky in The Marginal Review:

‘Anti-Semitism gave birth to Herzl, Herzl gave birth to the Jewish state, the Jewish state gave birth to ‘Zionism,’ and Zionism—the Congress.” With these words, the cultural Zionist Ahad Ha’am criticized the impetus for Theodor Herzl’s Zionism—anti-Semitism—and the political movement it created. But as his scare quotes suggest, Ahad Ha’am was not rejecting Zionism as such but rather Herzl’s “Zionism.” For Herzl, Zionism was a response to a decay in the external world—anti-Semitism—and he worked for a solution coming from that world—a Jewish state. In contrast, for Ahad Ha’am, Zionism was a response to an inner decay of Jews and Judaism: it was first and foremost the work of Jews transforming and resurrecting Judaism and Jewishness by way of a renaissance of Hebrew culture.

Elad Lapidot’s important and provocative new book, Jews out of the Question: A Critique of Anti-Anti-Semitism, is not implicitly concerned with debates about Zionism. But the problem that he outlines resonates with the spirit of Ahad Ha’am’s strong repudiation of a modern temptation to define Jews and Judaism in terms of anti-Semitism. If Herzl’s Zionism was the child of anti-Semitism, Lapidot’s anti-anti-Semitism, which includes positions that Lapidot identifies with a large variety of European philosophers, including Hannah Arendt, Jean-Paul Sartre, Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Alain Badiou, and Jean-Luc Nancy, among others, is its sibling. And just as Ahad Ha’am thought that Herzl’s anti-anti-Semitism, i.e. his Zionism, had grave implications for Jews, Judaism, and Jewishness, so too Lapidot laments that twentieth and twenty-first century anti-anti-Semitism is similarly consequential.’

(…)

‘Lapidot does not utilize the category of essentialism; however, anti-anti-Semitism, the object of his book’s critique, can be understood as a kind of anti-essentialism, from both metaphysical as well as socio-political points of view. As a metaphysical doctrine, essentialism is a claim that some features of an object of knowledge are necessary conditions for an object to be what it is (for instance, lead may be essential to a pencil while wood or plastic may not). As a psychological or sociological concept, social essentialism is the view that certain social categories necessarily define different kinds of people. Prejudice and stereotypes are of course the most obvious forms of social essentialism.’

(…)

‘Lapidot’s basic point is that anti-anti-Semitism is not just the denial of any particular essence that could be said to belong to Jews but is opposition to the very possibility of even considering the question of what could define Jews. This is the meaning of Lapidot’s title: anti-anti-Semitism places knowledge of Jews out of the question.’

(…)

‘Social construction moves away from falsely defining identity as fixed towards an acknowledgment of the power relations that produce identity. From this point of view, neither lead nor wood nor plastic is essential to a pencil. Rather, as the creation of smart pencils show, when thinking about what a pencil “is,” we should focus as much on the powers of the tech industry as on new technologies. So too there are no essential races or genders that lie beneath the structural powers that construct them.’

(…)

‘If one accepts this argument, one might think that an obvious solution might be simply to let groups and individuals speak as knowers of themselves and the traditions they believe define them. For instance, J.K. Rowling and Judith Butler each propound epistemic claims regarding gender, just as Anthony Appiah and Ibram X. Kendi each offer accounts of race, and just as Benjamin Netanyahu and Peter Beinart each advance narratives of the Jewish community. Sexism, racism, and anti-Semitism still exist of course. But alternative accounts of gender, race and Jewishness engage with these pernicious ideologies on the battleground of knowledge of knowledge.’

(…)

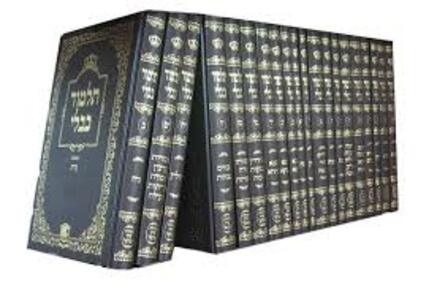

‘Lapidot does not want to be emancipated. Rather, he wants to return, or at the very least, to turn towards what he regards as genuine Jewish episteme: Talmud. His argument against anti-anti-Semitism is “an introduction to Jewish thought, to thinking as it has historically been deployed in and as Jewish being, to thinking as machloykes [Yiddish for disagreement]. Anti-anti-Semitism is introduction to Talmud.”Despite his indictment of Arendt, Lapidot agrees with her claim that in modernity, what had been collective Jewish identity tied to Judaism has degenerated into a psychology of Jewishness. It is for this reason that he claims that anti-anti-Semitism rejects not only the possibility of Jewishness but also of Judaism (what Lapidot often calls “the Jewish”).’

(…)

‘Second, he maintains that Heidegger’s presentation of Dichtung is best understood as a discourse of holiness grounded in distance from, rather than closeness to, God and in homelessness and wandering, rather than homeland. This, it turns out, is pretty close to what Lapidot means by “Talmud,” which he calls the “nonbiblical” Jewish, which might offer a mode of thought other than the philosophical and a mode of politics other than the state. Lapidot’s anti-anti-anti-Semitism saves not only Heidegger but also the “nonbiblical” Jewish.’

(…)

‘At the same time, on Lapidot’s own terms, I should be suspicious of my inclination to think that Jewish thought ought to emerge primarily, though not exclusively, not just from explicitly Jewish texts but also from people who understood themselves to be Jewish. As he states, the “horizon for the emergence” of Jewish thought that “opens access to the non-biblical Jewish” is “perhaps even non-Jewish Jewish, namely the Talmud.” The irony here, however, is that a study which insists on acknowledging what it calls the deficiency in the modern relation between politics and knowledge offers an account of politics that cannot but seem fundamentally apolitical. But perhaps this is not ironic but exactly Lapidot’s point.’

(…)

‘Lapidot concludes his important study with the following promissory sentence: “In the horizon of political epistemology…any attempt to think Talmud beyond Greco-Judeo-Christian thought, would have to contemplate just as fundamentally the performative mode of language that we call law.”’

Read the review here.

The main problem is this: a Jew who is not religious, for whom the Talmud is as important as the Koran let’s say, can still be Jewish of course but his Jewishness is defined by antisemites or by anti-antisemites. And as we could have guessed and Batnitzky explains this (with the help of Lapidot), anti-antisemitism follows the logics of antisemitism.

Is there anything we can know about Jews beyond the social construct that largely consists of negative stereotypes that are thereafter softened by well-meant apologies, in my experience. (‘But Jews were not allowed to do this, to do that, so what else could they do than become a banker?’)

Essentialism is a bit grizzly, less so while talking about objects like pencils, but when it comes to humans, yes. My essence is very private.

That anti-antisemitism like antiracism is not so clear, more complex and sometimes nasty, as is often thought might be well-known by now.

We can study the history of the Jews and this will result in knowledge but probably by doing this we don’t know much yet about all Jews living today.

And also this, Lapidot might not want to be emancipated. Fair enough, emancipation has a bad reputation in almost all circles, but the desire to become an invisible part of the majority deserves more scrutiny.

Especially in times where victimhood became cultural (and sometimes economical) capital, the performance of victimhood is an entry ticket to many desirable parlors.