On biology – The Economist:

‘Ms Huitson is not alone in having a dysfunction in the brain mistaken for one in the mind. Evidence is accumulating that an array of infections can, in some cases, trigger conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, tics, anxiety, depression and even psychosis. And infections are one small piece of the puzzle. It is increasingly clear that inflammatory disorders and metabolic conditions can also have sizeable effects on mental health, though psychiatrists rarely look for them. All this is symptomatic of large problems in psychiatry.’

(…)

‘There is so much overlap between the symptoms of depression and anxiety, for example, that some wonder if these are actually even separate categories of illness. At the same time, depression and anxiety come in many different subtypes—panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, for example, are distinct diagnoses—not all of which may be meaningfully distinct. This can lead to patient groups in drug trials being so diverse that drugs and therapies fail simply because the cohort being studied has too little in common.’

(…)

‘But it is also sometimes found in adults. One 64-year-old man reported spending an extraordinary amount of time obsessively trimming his lawn only to look back on this behaviour the next day with feelings of regret and guilt. Researchers found these symptoms were being caused by antibodies attacking the neurons in his brain.

More recently, Belinda Lennox, head of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, has conducted tests on thousands of patients with psychosis. She has found increased rates of antibodies in the blood samples of about 6% of patients, mostly targeting the nmda receptors. She says it remains unknown how a single set of antibodies is capable of producing clinical presentations ranging from seizures to psychosis and encephalitis. Nor is it known why these antibodies are made, or if they can cross the blood-brain barrier, a membrane that controls access to the brain. She assumes, though, that they do—preferentially sticking to the hippocampus, which would explain how they affect memory and lead to delusions and hallucinations.’

(…)

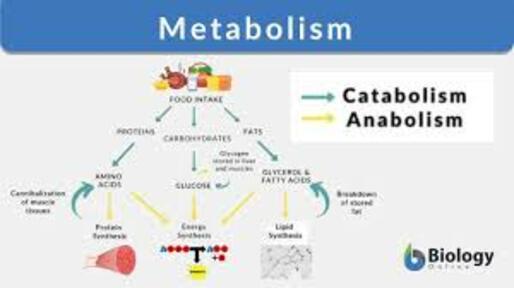

‘Another important discovery is that metabolic disturbances can also affect mental health. The brain is an energy-hungry organ, and metabolic alterations related to energy pathways have been implicated in a diverse range of conditions, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, psychosis, eating disorders and major depressive disorder. At Stanford University there is a metabolic psychiatry clinic where patients are treated with diet and lifestyle changes, along with medication. One active area of research at the clinic is the potential benefits of the ketogenic diet, in which carbohydrate intake is limited. This diet forces the body to burn fat for energy, thereby creating chemicals known as ketones which can act as a fuel source for the brain when glucose is in limited supply.

Kirk Nylen, head of neuroscience for Baszucki Group, an American charity that funds brain research, says 13 trials are under way worldwide looking at the effects of metabolic therapies on serious mental illness. Preliminary results have shown a “large group of people responding in an incredibly meaningful way.’

(…)

‘All such developments are promising. But many of the field’s problems could be resolved by relaxing the distinctions that exist today between neurology, which studies and treats physical, structural and functional disorders of the brain, and psychiatry, which deals with mental, emotional and behavioural disorders. Dr Lennox finds it extraordinary that the treatment options differ so completely if a patient ends up on a neurology ward or a psychiatric ward. She wants antibody testing to be more routine in Britain when someone presents with a sudden post-viral mental illness that does not get better with standard treatments. Thomas Pollak, a senior clinical lecturer and consultant neuropsychiatrist at King’s College London, says mri scans should probably be used on patients after their first episode of psychosis as, in 5% to 6% of patients, it would change the way they are treated.

This rift between neurology and psychiatry is greater in Anglo-Saxon countries, says Dr Tebartz van Elst. (These are countries including America, Britain, Canada, and New Zealand.) In Germany, psychiatry and neurology are more integrated, with neurologists training in psychiatry, and psychiatrists doing a year of neurology as part of their training. That makes it easier for investigational work to be done. He says he offers most patients with first-time psychosis or other severe psychiatric syndromes an mri of the brain, an electroencephalogram, lab tests for inflammation, and a lumbar puncture to find evidence to support different treatments in some patients. The price tag, around €1,000 ($1,070), is no more than the cost of hospitalising a patient for three or four days, says Dr Tebartz van Elst, so may be good value for money.’

(…)

‘Biology is coming, whether psychiatry is ready or not.’

Read the article here.

Once and for all, mind and body are inseparable.

The coming of biology doesn’t necessarily mean the end pf psychoanalysis and therapy. In New York, and probably not only in new York, therapy is a status symbol. If you want a date you most prove that you are in therapy.

Living without a therapist is almost the same as being homeless.

But if you want to cure or ameliorate mental problems change lifestyle and diet, it won’t be a miracle ointment but in quite a few cases it will help.

Also, this has been known for quite some time.

It’s not your youth, it’s an inflammatory disorder.