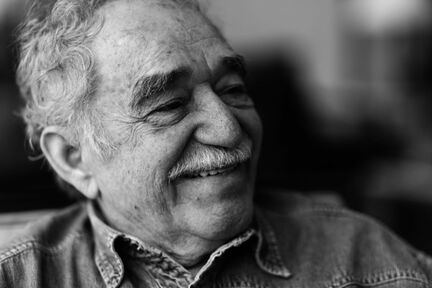

On a posthumous Márquez – Miranda France in TLS:

‘One of Gabriel García Márquez’s shortest books has a title so long that it occupies the entire front cover: The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor: Who drifted on a liferaft for ten days without food or water, was proclaimed a national hero, kissed by beauty queens, made rich through publicity, and then spurned by the government and forgotten for all time. (I’ll spare you the Spanish title.) The book, first published in 1970, is a work of reportage that originally appeared in 1955 as a series in El Espectador de Bogotá; yet the trajectory of that long sentence contains all the elements that García Márquez prized in fiction: drama, pathos and excess.’

(…)

‘García Márquez is one of those rare authors who catch and ride a global wave. He belonged to a group of writers, also including Mario Vargas Llosa, Julio Cortázar and Carlos Fuentes (the “Boom generation”), who made it glamorous, and not simply wholesome, to read translated fiction. For a time in the 1980s it felt as though every bedside table was propping up a hefty García Márquez novel. Through his translators – first Gregory Rabassa, then Edith Grossman – anglophone readers became aware of a part of Latin America they hadn’t thought of before: the sultry, tropical Caribbean coast of Colombia, so different from the world of Jorge Luis Borges, another literary giant, but brought up with an English nanny at the other end of the continent, in cosmopolitan Buenos Aires.’

(…)

‘He would later describe his first three novels as an apprenticeship for One Hundred Years of Solitude, the book in which he finally discovered the tone – a mixture of nostalgia and invention, infused with the melancholy of his Galician-descended grandparents and an Afro-Caribbean sensibility – that he had been looking for to create the world of Macondo and the travails of the Buendía family. Written in eighteen months, the novel was described by Pablo Neruda as “perhaps the greatest revelation in the Spanish language since the Don Quixote of Cervantes”. But García Márquez was uneasy about the “magical realism” tag it soon acquired, claiming he had invented nothing. “Our reality is in itself out of all proportion”, he told Mendoza.

“How can the reader imagine the Amazon which at certain points is so wide you can’t even see across it? The word “storm” conjures up one thing for the European reader and quite another for us. The same applies to the word “rain”, which cannot possibly convey the torrential downpours of the tropics.”

Exaggerations have always been an ingredient of folklore. We don’t have to take literally the ascension into heaven of Remedios the Beauty while hanging out the washing – it’s just another tall tale. For centuries, after all, family scandals have been covered up with unlikely stories.’

(…)

‘Count this reader among the undelighted. Until August is a recognizably Marquezian fable, stripped down to its basics. There are flashes of the author’s trademark charm: flowers, Caribbean gentlemen in linen suits, the scent of jasmine. Some of the old tricks and artifices are there, but all the subtlety is gone. The author’s once rich vocabulary is noticeably diminished.

The novel – which has been deftly translated by Anne McLean – opens with a boat trip through the jungle, recalling the heady opening to Living to Tell the Tale, in which García Márquez describes returning with his mother to Aracataca, where she plans to sell the family home, the engine room of all his writing. As the story progresses, Ana Magdalena Bach is to take four annual trips to an unnamed island, to lay gladioli on the grave of her mother. García Márquez loves habits as much as hyperbole, so Ana Magdalena, forty-six at the start of the novel, always has a cheese and ham sandwich at the end of her journey. In her hotel bedroom, on the first journey, she appraises her breasts in the mirror, then lies on the bed “wearing nothing but her lace panties” and reads Dracula (later in the novel she will read The Day of the Triffids, A Journal of the Plague Year and The Ministry of Fear; clearly she has a thing for British novelists). Then, after dinner, Ana Magdalena spontaneously invites a fellow guest up to her room for sex.’

(…)

‘Chronicle of a Death Foretold (Crónica de una muerte anunciada, 1981), the author’s own favourite, took thirty years to grow from an anecdote told him by a friend into the tale of a whole community complicit in murder. The General in His Labyrinth (El general en su laberinto, 1989) follows Simón Bolívar on his last journey, heartsick and devastated by the failure of his vision for a united continent. Few writers have bequeathed such riches to posterity. While there is an argument that it’s interesting to observe a celebrated author continuing to write “against the odds”, that could have remained an exercise for the archive. It is sad to see this great Boom writer going out with a whimper.’

Read the review here.

If Márquez is ‘drama, pathos and excess’ then Isaac babel is: drama, lyrical understatement and excess.

My favorite Márquez is ‘Chronicle of a Death Foretold’ but perhaps I was too young when I read ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude.’

‘My Melancholy Whores’ was already slightly sleezy indeed, but I’m willing to forgive great authors sleeziness.