On definitions - Eyal Press in The New Yorker:

‘In November, 2017, Kenneth Stern appeared before the House Judiciary Committee to testify about a bill under consideration, the Anti-Semitism Awareness Act. Approved by the Senate a year earlier, the bill would require the Department of Education to apply a specific definition of antisemitism when investigating alleged cases of discrimination against Jews on college campuses. Stern, a lawyer and scholar who served for twenty-five years as the American Jewish Committee’s in-house expert on antisemitism, had devoted much of his career to highlighting the hatred and intolerance that threatens Jews. He was also the lead drafter of the definition cited by the bill, a definition that he had once urged both State Department officials and foreign policymakers to embrace.

Yet, at the congressional hearing, Stern struck a different note. The definition, which had been written in 2004 and adopted, in 2016, by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (I.H.R.A.), an intergovernmental organization based in Stockholm, was created to help governments collect data on antisemitism, he said. It “was not drafted, and was never intended, as a tool to target or chill speech on a college campus.” Stern was particularly concerned about a section of the definition that listed eleven contemporary examples of antisemitism, among them “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination” and holding Israel to “double standards” that were not expected of other nations.’

(…)

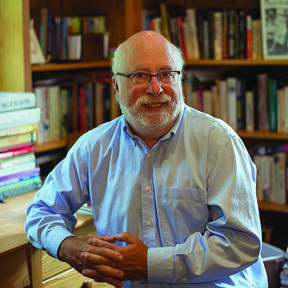

‘Within the Palestine-solidarity movement, there is a widespread belief that defenders of Israel have used the I.H.R.A. definition to censor speech and silence legitimate criticism. What’s unusual about Stern is that he shares this concern despite being a defender of Israel himself. “I’m a Zionist,” he told me when we met recently at his home in Brooklyn, where he lives with his wife, Margie, a rabbi. Stern is seventy-one, with a scruffy white beard and a taste for casual attire. On the day I visited, he was wearing house slippers and nursing a slight cold. Since 2018, he has commuted frequently from Brooklyn to Annandale-on-Hudson, where he directs the Center for the Study of Hate, at Bard College. He’d had an unusually busy fall, in part because of the national debate about how universities should address the tensions fuelled by the Israel-Palestine war. Stern’s most recent book, “The Conflict Over the Conflict,” is about this very subject. Published in 2020, it received almost no attention when it came out, he told me. But, at a recent Jewish-studies conference, it was “selling like hotcakes,” and Stern suddenly found himself in high demand, fielding a slew of speaking invitations, media inquiries, and calls from university presidents asking him to address their boards. “It’s been crazy,” he said.’

(…)

‘But Stern’s aversion to speech codes was also shaped by another, more practical consideration. While working for the A.J.C., he wrote a report about the white supremacist David Duke, who, in 1969, while attending Louisiana State University, gave a speech calling for Black people to be sent to Africa and for Jews to be exterminated—and then, the following year, paraded around Tulane University in a Nazi uniform, in protest of an attorney who defended the Chicago Seven. These acts were vile, but no one tried to silence or prosecute Duke. Had this been done, Stern concluded, the debate might have shifted from his hateful message to whether such expression should be allowed, enabling Duke to portray himself as the victim of an assault on the First Amendment.’

(…)

‘In 2021, an alternative definition called the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism sought to draw finer distinctions. In the preamble, it stated, “Hostility to Israel could be an expression of antisemitic animus, or it could be a reaction to a human rights violation, or . . . the emotion that a Palestinian person feels on account of their experience at the hands of the State.” The Declaration went on to list some examples that were antisemitic, such as “holding Jews collectively responsible for Israel’s conduct,” and others that were not. “Criticism that some may see as excessive or contentious, or as reflecting a ‘double standard,’ is not, in and of itself, antisemitic,” it affirmed. “Opposing Zionism as a form of nationalism” was also not, on its face, antisemitic.’

(…)

‘Stern tells this story in “The Conflict Over the Conflict,” a work that is unlikely to please partisans. The book makes the case for bridging differences and recognizing nuance. It also describes Israeli-Palestinian history as an “ideal subject” to teach at universities, precisely because it is so divisive. At the West End Temple, Stern reiterated this belief. “On college campuses, students have an absolute right to expect they’re not going to be harassed, they’re not going to be bullied,” he said. “But to be disturbed by ideas is O.K.: we want students to be disturbed by ideas and to figure out how to think about them.”’

(…)

‘A month earlier, he told me, he’d spoken to a journalist who wanted guidance: “ ‘Is this antisemitic, is that antisemitic?’ ” Stern replied that this was the wrong question. “The question is, Why is this so binary that we want to label it this way or that way?”’

Read the article here.

Stern’s position is reasonable and prudent.

It’s hard to define exactly where anti-Semitism begins, the same can be said about racism, and a too broad definition can easily be used tto silence those with whin you disagree.

A frivolous use of the word anti-Semitic also hurts the fight against it.

Where anti-Zionism ends and anti-Semitism begins s hard to say.

But too often, both in the US and Europe (let's forget Israel for moment) the fight against antisemitism is used as a fight in another war. A fight against newcomers who sometimes seem to be slightly more antisemitic than the so-called original population.

Speaking of myopia.