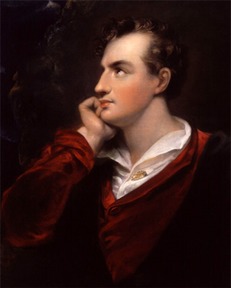

On Byron - Miranda Seymour in NYRB:

‘Byron might have found it faintly funny that his funeral rites at Missolonghi, the small Greek coastal town where he died in the spring of 1824, included the ceremonious placing of his own showy headgear upon the coffin, beside a sword. The tribute was, however, in keeping with the melancholy wish Byron expressed in the poem that ended his final journal, “On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year,” for “a soldier’s grave.” Nobody understood better than John Murray, the canny Scottish publisher who made a fortune from selling Byron’s works to an adoring public, the commercial value of the poet’s knowing identification of himself with his subjects. Hard though the going sometimes proved to be, it was worth the shrewd bookseller’s time and patience to stay on excellent terms both with his most successful author—even after he refused to publish the final, buoyantly scurrilous cantos of Don Juan—and with Annabella Milbanke, Byron’s devoted but incurably self-righteous wife and widow. From the gloomily aloof hero of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage(whose far-flung travels were accompanied from edition to edition by engraved plates showing his handsome creator visiting those same exotic locations) to the mocking, chattily transgressive narrator of Don Juan, Byron maintained an extraordinary ability to convince his readers that each one of them had a secret hotline to his attentive ear, if not to his generously shared bed.’

(…)

‘Byron today is more famous than read. Despite his literary influence—Pushkin and Stendhal, for example, are unimaginable without him—his reputation is up for assessment and strategic repositioning in the bicentennial year of his death.’

(…)

‘The change of attitude toward sexual ethics since the last major celebration of Byron (the 150th anniversary of his death in 1974) has been great. Introducing the first volume of his letters in 1973, Leslie Marchand evidently felt no qualms about describing his uninhibitedly promiscuous subject as the “ravished” victim (“Poor dear me,” Byron sighed to a male friend) of a pack of obsessed women “who forced their attention on him.” After the public exposures of Harvey Weinstein, Jeffrey Epstein, and sundry other tarnished figures, that argument feels as awkward as Marchand’s chilling denunciation of Claire Clairmont, the mother of Byron’s lively, short-lived daughter Allegra, as the sole instigator of “an unfortunate and unwanted affair.” How would Byron fare today with the defense that he sheepishly submitted to his loyal friend Douglas Kinnaird: “A man is a man—& if a girl of eighteen comes prancing to you at all hours—there is but one way”? Really, m’lud?’

(…)

‘Less fixated than Byron’s most recent biographer, Antony Peattie,

on the impact of his physical disability (a deformed foot and consequently withered calf led this intensely self-conscious man to adopt loose-fitting pantaloons and shun the dance floor) and an enduring, obsessive battle to keep his weight down, Stauffer has more to say about what he calls the “dark side” of Byron: the “gothic episodes of depression” and “continual acts of sabotage” that caused his increasingly apprehensive wife to wonder if he was mad.

Was he? All Byron himself was willing to admit, while living in Venice, was that his temper, when provoked, was said to be “rather a savage sight.” At Cephalonia, his capacity for rage was memorably demonstrated during a visit to a monastery. After screaming at the alarmed abbot, the recently arrived guest darted into a side room and, tearing off his clothes and hurling a chair at the door, began to rave: “Back! Out of my sight! Fiends, can I have no peace, no relief from this hell?” Stauffer’s verdict on Byron’s “strange behaviour” as “likely triggered by exhaustion, alcohol, and overexertion in the heat” feels inadequate. It is, however, in keeping with this gentle biographer’s observation of Augusta Leigh, the intrusive, tactless half-sister who saw no harm in linking her initials with Byron’s on a Newstead tree the day after his engagement to Annabella Milbanke, that she “was not good at drawing boundaries.” Quite.’

Read the article here.

Quite.

Nowadays Lord Byron would have been more careful, and perhaps the boasting about his sexual adventures has always been a bit rude.

My most vivid memory of Lord Byron is the supporting role that Coetzee assigned him in ‘Disgrace.’ His Davis Lurie most probably wanted to be a Lord Byron in his time, but one is enough.

A generously shared bed is an act of generosity but for tad of reasons people prefer other types of generosity these days.

Not good at drawing boundaries indeed. The artist used to be a scoundrel, nowadays the artist is supposed to be a saint. Apparently, saintliness and success go well together.