Tom McCarthy in LRB on the real and literature:

“There’s been a lot of talk in recent years about reality in fiction, or reality versus fiction. Take the many articles about the ‘true’ writings of Karl Ove Knausgaard, or the huge amount of attention paid to David Shields’s polemic Reality Hunger. Time and again we hear about a new desire for the real, about a realism which is realistic set against an avant-garde which isn’t, and so on. It’s disheartening that such simplistic oppositions are still being put forward half a century after Foucault examined the constructedness of all social contexts and knowledge categories; or, indeed, a century and a half after Nietzsche unmasked truth itself as no more than ‘a mobile army of metaphors, metonymies, anthropomorphisms … a sum of human relations … poetically and rhetorically intensified … illusions of which one has forgotten that they are illusions’ (and that’s not to mention Marx, Lyotard, Deleuze-Guattari, Derrida etc). It seems to me meaningless, or at least unproductive, to discuss such things unless, to borrow a formulation from the ‘realist’ writer Raymond Carver, we first ask what we talk about when we talk about the real. Perhaps we should have another look at the terms ‘the real’, ‘reality’ and ‘realism’.

Let’s start with ‘realism’, since it’s the easiest target of the lot. Realism is a literary convention – no more, no less.”

Realism is a literary convention, absolutely and McCarthy is also right when he remarks: “It turns out that the 20th-century avant-garde often paints a far more realistic picture of experience than 19th-century realists ever did.” Absolutely, but this raises immediately the question whether we need literature to get a ‘realistic’ picture of experience.

We can agree on this: there is a connection between the text and the world outside the text, often described as “reality”.

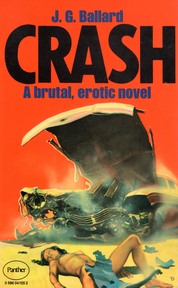

Now let’s go to the Ballard quote with which McCarthy begins his article: “We live inside an enormous novel. It is now less and less necessary for the writer to invent the fictional content of his novel. The fiction is already there. The writer’s task is to invent the reality.”

This is a paradox, and a dangerous paradox for that matter, because if the novelist takes his task of inventing reality a tad too seriously he may end up as a rather bloodthirsty politician. (Most novelists don’t have the perseverance, the lust for risk, the bloodthirstiness and the skill to manipulate masses for this endeavor.) I stick to the probably old-fashioned notion that the novelist should disclose reality or perhaps I should say the real, but I’m perfectly aware that this reality is a construct. The real is not reality.

What’s the real? It’s a moral category, or at least it comes very close to being a moral judgment.

McCarthy again: “In one sense, then, the real is connected to trauma, and in another sense to matter. But these aren’t really two separate categories. For Freud, psychic trauma is a material phenomenon, since all mental existence is material: in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, he defines the organism – human or otherwise – as being, at root, ‘an undifferentiated vesicle of a substance that is susceptible to stimulation’.”

Yes, the real is the trauma, the pain to a certain degree, death of course. Reality may be nothing but layers of constructedness, but this is of less concern to you if you are in a war zone, or if you are in a room being tortured by reliable civil servants.

The real is the horror, the absolute powerlessness; it’s the moment when all human defense mechanisms appear to collapse. We don’t need a war zone to enter the real, but the real is definitely more tangible there.

We may live inside an enormous novel, probably we do, but the trauma is not fictional, the trauma is real.

Read Tom McCarthy’s piece here.