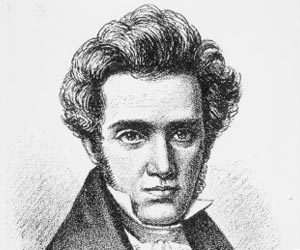

Peter E. Gordon on Kierkegaard in NYRB:

'Hampson is a dutiful expositor and her summaries can be a bit dry when she keeps her opinions in check. But once she has departed from the task of exposition her critical voice is thoughtful and unconstrained by orthodoxy. Surely the explanation for this is, in part, the fact that Hampson does not share Kierkegaard’s beliefs. Although she favors some kind of “spirituality,” she rejects traditional monotheism, especially its patriarchal themes, and she considers the notion of a God who resides “outside” the world the remnant of a defunct metaphysics. In the preface, after she has listed her debts to teachers and colleagues she permits herself the unusual gesture of thanking S.K. himself:

My life would have been subtly different had I not encountered Kierkegaard. He has been a source of delight and edification with his insights and perspicacity. I am moved by his love of God, his sensitivity to others, and his sparkling wit.

But, she adds, Kierkegaard has also helped her to grasp “with greater clarity why I should not wish to be Christian.”'

(...)

More worrisome, in my view, is not Kierkegaard’s lapse into anthropomorphism but rather the opposite: his readiness to amplify the doctrine of Protestant abstraction to a limit where the divine exceeds all understanding. Kierkegaard’s God lies at such a great remove from everyday categories as to contravene our most fundamental and enduring norms of morality. When a parent believes he hears voices that command him to take a knife to his own child our proper response should be not praise for his piety but horror at his self-evident lunacy. Kierkegaard is of course aware that this is our customary belief. But he sees in Abraham’s conduct a “teleological suspension of the ethical,” which is to say, he entertains the thought that religion imposes a higher purpose on us than what ethical reasoning demands.

(...)

'Ironically, the desire to stand as an authentic individual beyond all such traditions is the greatest conceit of the bourgeois era and Kierkegaard was in this respect far more conformist than he cared to admit. And yet none of us wishes wholly to surrender this desire for authenticity since it is also the very sign of possibility itself, the hope that life might be otherwise than it is. To abandon this hope is to give up on possibility altogether. Against all the forces that counsel resignation Kierkegaard remains not just the knight of faith but something more: the eternal child.'

Read the article here.

The eternal child is what attracts us to (some) artists. Much more than philosophers they manage to display their eternal child with impunity.

Till what age can we remain an eternal child? Till death? Till we have children?

And what does it mean to be an eternal child? Fearful, cheerful, desperate, curious, abandoned and always in search of an authority?

Is it a blessing to be an eternal child or a curse? Kierkegaard's life suggests the latter.