Mark Glanville in TLS on Avrom Sutzkever:

'Avrom (or Abraham) Sutzkever wrote poetry in a language whose speakers and readers were almost entirely wiped out during the Holocaust. While the novelist Isaac Bashevis Singer went on to acquire a large audience and a Nobel Prize, chiefly thanks to excellent English translations he himself had a hand in, the vast output of the greatest Yiddish poet has remained, on the whole, accessible only to a rapidly diminishing, secular, Yiddish-speaking population. Barbara and Benjamin Harshav’s volume of impressionistic, English-only versions published in 1991 did little to convey the power of the originals. It is impossible to appreciate Sutzkever’s verse without at least seeing it in Yiddish and gaining some sense of how the poet bent the language to his purpose, much as Paul Celan did with German. Sutzkever was unafraid to forge his high-poetic Yiddish out of a street “jargon” that had not previously been associated with serious literary culture, creating neologisms at will – but always within the context of strict poetic forms. Sutzkever’s employment of metre and rhyme themselves present considerable difficulty to his translators.

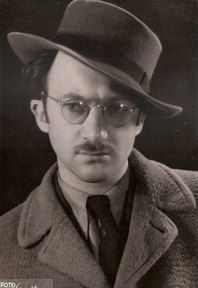

Sutzkever was born in 1913 in what is now Belarus, though his earliest years were spent in Omsk, in Siberia. His father died when he was eight, and his mother moved the family to Vilnius, where Abraham attended Polish Jewish high school. It is easy to regard him as a poet of the Holocaust: he was undoubtedly one of its greatest literary witnesses, but until the German invasion of Lithuania in 1941 he had not considered politics and current affairs to be the proper stuff of poetry. As Justin Cammy, in his excellent introduction to The Full Pomegranate, points out, “his poetry was marked from its earliest articulations by a fascination with nature . . . he fiercely privileged the aesthetic integrity of the poem itself over any prosaic cause it might serve”. In this Sutzkever was at odds with his fellow poets in the Yung-Vilne (Young Vilnius) movement. While they were enlisting Yiddish poetry in the service of the revolutionary struggle, Sutzkever’s verse, heavily influenced by the hermetic Polish poet Cyprian Norwid, focused more on the self, and was distinguished by pantheistic natural imagery. His writing appealed more to the New York-based “Inzikhistn” (Introspectivists), who included Yankev Glatshteyn. But under the brutal occupation, during which Sutzkever’s mother and newborn son were murdered by the Nazis, “he increasingly developed a sense of vocation as a witness to his own and future generations. He felt a compulsion to reconcile beauty and horror, to give form to chaos”, writes Heather Valencia. For Sutzkever, we learn in Black Honey, an excellent recent Israeli documentary on his life, poetry was “something miraculous, prophetic, divine”, that enabled him to survive – in one instance, literally.

In 1943 Sutzkever and his wife Freydke, escaping from the Vilna Ghetto, went into hiding in the forests where he fought with a Jewish unit of the partisan resistance. “Kol Nidre”, his long, harrowing Holocaust poem of that year, had brought him to the attention of the Jewish anti-Fascist Committee in Moscow, who sent a plane to rescue them. In order to reach the plane, the couple had to negotiate a minefield. Sutzkever solved the problem by crossing it in metre. “Sometimes I walked in anapaests, sometimes in amphibrachs.” “Each section of the minefield”, explains his friend, the poet Dory Manor, “had its own rhythm, an entire prosody of life-saving.”'

Read the review here.

It's hard to get a good sense of the quality of Sutzkever's poetry, but to cross a minefield in metre is enough to give us a sense of the reconciliation of beauty and horror.