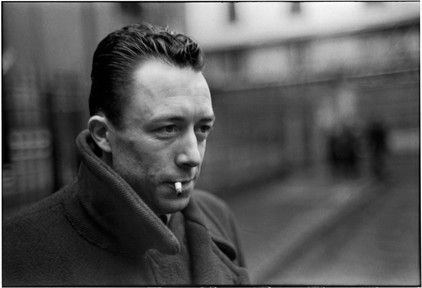

Ryan Bloom in The New Yorker on what's lost in translation, or maybe not:

'For the modern American reader, few lines in French literature are as famous as the opening of Albert Camus’s “L’Étranger”: “Aujourd’hui, maman est morte.” Nitty-gritty tense issues aside, the first sentence of “The Stranger” is so elementary that even a schoolboy with a base knowledge of French could adequately translate it. So why do the pros keep getting it wrong?

Within the novel’s first sentence, two subtle and seemingly minor translation decisions have the power to change the way we read everything that follows. What makes these particular choices prickly is that they poke at a long-standing debate among the literary community: whether it is necessary for a translator to have some sort of special affinity with a work’s author in order to produce the best possible text.

Arthur Goldhammer, translator of a volume of Camus’s Combat editorials, calls it “nonsense” to believe that “good translation requires some sort of mystical sympathy between author and translator.” While “mystical” may indeed be a bit of a stretch, it’s hard to look at Camus’s famous first sentence—whether translated by Stuart Gilbert, Joseph Laredo, Kate Griffith, or even, to a lesser degree, Matthew Ward—without thinking that a little more understanding between author and translator may have prevented the text from being colored in ways that Camus never intended.

Stuart Gilbert, a British scholar and a friend of James Joyce, was the first person to attempt Camus’s “L’Étranger” in English. In 1946, Gilbert translated the book’s title as “The Outsider” and rendered the first line as “Mother died today.” Simple, succinct, and incorrect.'

(...)

'So how is the English-language translator to avoid unnecessarily influencing the reader? It seems that Matthew Ward, the novel’s most recent translator, did the only logical thing: nothing. He left Camus’s word untouched, rendering the famous first line, “Maman died today.” It could be said that Ward introduces a new problem: now, right from the start, the American reader is faced with a foreign term, with a confusion not previously present. Ward’s translation is clever, though, and three reasons demonstrate why his is the best solution.

First, the French word maman is familiar enough for an English-language reader to parse. Around the globe, as children learn to form words by babbling, they begin with the simplest sounds. In many languages, bilabials such as “m,” “p,” and “b,” as well as the low vowel “a,” are among the easiest to produce. As a result, in English, we find that children initially refer to the female parent as “mama.” Even in a language as seemingly different as Mandarin Chinese, we find māma; in the languages of Southern India we get amma, and in Norwegian, Italian, Swedish, and Icelandic, as well as many other languages, the word used is “mamma.” The French maman is so similar that the English-language reader will effortlessly understand it.'

Read the article here.

Bloom claims that the word 'mother' has a hint of coldness in it, distance. I'm not so sure. The distance is part of Meursault, it belongs to him, and distance and coldness are not the same.

'Maman' might be a better option, better than mom that reminds me, I'm not sure why, of American suburbia. But I've nothing against the word 'mother.'

It's important to accept that distance is not necessarily a sign of lack of affection. We seem to be so used to faux emotions that we cannot do without them.