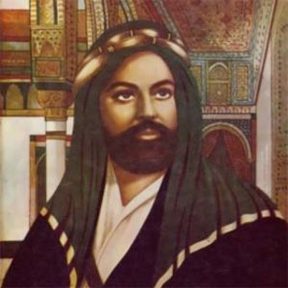

On Muhammed and his Jewish biographer – Tariq Ali in LRB:

“The most stimulating, balanced and sympathetic secular biography of the Prophet of Islam was written by a left-wing French Jewish intellectual in 1961. Maxime Rodinson’s Life of Muhammad was a formative influence on my generation. It seemed to be the first real attempt to come to terms with a culture that could not be understood through sacred texts or works of exegesis alone. Rodinson’s intellectual trajectory was indelibly linked to his personal and political biography. His parents, like many other Russian Jews, had fled the tsarist pogroms of the late 19thcentury, ending up in Marseille, where his father worked in the clothing trade. Maxime, who was born in 1915, left school at the age of twelve to work as an errand boy. His parents had backed the Russian Revolution, and in its wake joined the French Communist Party. But their refuge in France was short-lived. They were dispatched to Auschwitz by Hitler’s French auxiliaries. It’s worth recalling that the herding up and dispersal of French Jews was at least in part a Vichy initiative. It’s a sordid history that the Gaullists and their successors (of most political persuasions) effectively covered up for decades. The reintegrated fascists played a horrific role during the Algerian war in both colony and metropolis.’

(…)

“He died in 2004. Three years earlier, in an interview with Le Figaro published as an appendix to this new edition of Muhammad, he argued that violence wasn’t any more intrinsic to Islam than it was to other religions.”

(…)

“Rodinson begins by describing the world into which Muhammad was born. Rome besieged by barbarians; Constantinople giving an impression of serenity and solidity, its confident and complacent rulers gazing on the Golden Horn, unaware of the rumblings in their lands; further east, the rulers of Persia failing to recognise that their kingdom was in terminal decline. Islam was, Rodinson explains, the last of the three monotheistic religions, after Judaism and Christianity, that met the social and economic needs of semi-nomadic trading communities in the Arab East. Early Christianity worked away patiently at the Roman Empire, with martyrdom helping to diffuse its ideas. The Trinitarians laid the foundations for a serious challenge to paganism and Constantine’s conversion did the rest. Christianity was the main political, economic and religious rival that confronted the fledgling faith being created in Yathrib (Medina). The concurrent implosion of two huge empires, Byzantine and Persian, made the task of the new religion easier. Islamic armies swept into these collapsing worlds at astonishing speed and within a hundred years of the Prophet’s death in 632, Islam had extended itself through force of arms to the Atlantic coast – the al-gharb or Algarve – in the west, while its traders had reached Khanfu (Canton) in the east.

In the absence of much worthwhile Western scholarship, Rodinson’s analytical and rationalist biography had to rely on previous works in Arabic, including the Quran and the often unreliable hadith, compilations of the sayings and actions of the Prophet. Some of these texts are still disputed: each faction or sect picks and chooses what it needs.”

(…)

“Muhammad never claimed to be anything other than a human being: he was a Messenger of God, not the son of Allah, and not in direct communication with him. The visions were mainly aural: the Prophet heard the voice of Gabriel, who dictated the Quran on behalf of Allah. In a largely illiterate world, in which storytelling was rife and memories strong, history was transmitted orally. Muhammad was not the only travelling preacher at the time; his message caught on because the nomadic communities found it plausible. Sometimes he stated that on a particular matter (usually related to sexuality) he had asked Gabriel for advice and obtained his approval. Khadija became his first follower. Breaking with his tribe, which then subjected him to the most vicious slanders, pushed Muhammad to create a new movement. He came to realise that tribal divisions were exacerbated by the plethora of local gods and goddesses, with each tribe worshipping its own favourites. Monotheism was the solution. He chose Allah, one of the Arab gods, to be the sole divinity at the expense of other deities, including the extremely popular women goddesses, who are honoured in an earlier version of the Quran, but were dispensed with later when the tribes that worshipped them converted to Islam. A rigorous monotheism prevailed thereafter.”

(…)

“Muhammad’s death in 632 led to a factional war. He had made clear that his followers should never present him as anything other than a human being blessed by Allah. He was a simple messenger, not a maker of miracles. He did not choose a successor, and disputes over who should become caliph were the origin of the split between the Sunni and Shia branches of Islam. War erupted within the faith when the Umayyads, the peninsula’s first Muslim dynasty, which had itself replaced the non-hereditary leaders who first followed Muhammad, were themselves defeated and supplanted in 750 by the Abbasids, who represented the enlarged fiefdom of Islam and the newly converted non-Arab Muslims. One Umayyad prince, Abd al Rahman, fled to a different peninsula on the edge of the Atlantic and took power in al-Andalus, the name given by the Arabs to the whole of Muslim Spain.

The homage paid by Cervantes in Don Quixote to the heritage of Spanish Islam is seldom remarked on. (There isn’t a single reference to it in Harold Bloom’s weak, lazy introduction to Edith Grossman’s translation of 2003.) When he was writing the novel in the early 17th century Spain was racked by an economic crisis whose chief causes included the depopulation of the countryside after the expulsion of Spanish Muslims, and inflation following the arrival of large quantities of silver and gold from the New World. For nearly five hundred years the dominant culture and language in Spain and Portugal had been Arabic. In the opening pages of Don Quixote the narrator explains that he found the manuscript he is editing in the Alcana bazaar in Toledo and that it is written in Arabic. It’s an old language, he says, but there is another that is even more antique. He is referring to Hebrew and signalling his own Jewish origins, still denied by the Royal Spanish Academy. At one point the two anti-heroes reach an uninhabited village and cautiously reflect on the ethnic cleansing of Jews and Muslims. Towards the end of the novel, Sancho questions his master about the meaning of a word he has just used:

‘What are albogues?’ asked Sancho. ‘I’ve never heard of them or seen them in my life.’

‘Albogues,’ responded Don Quixote, ‘are something like candlesticks, and when you hit one with the other along the empty or hollow side, it makes a sound that is not unpleasant, though it may not be very beautiful or harmonious, and it goes well with the rustic nature of pipes and timbrels; this word albogues is Moorish, as are all those in our Castilian tongue that begin with al, for example: almohaza, almorzar, alhombra, alhucema, almacen, alcancia and other similar words ... I have told you all this in passing because it came to mind when I happened to mention albogues.’

But nothing is ever told ‘in passing’ in this courageous novel. It is perhaps the most carefully crafted work in European literature, both parts written in the shadow of the Inquisition. In another passage, Cervantes gives Sancho some lines whose reference to the expulsion of the Muslims and Jews is unmistakeable: ‘I’d like your grace to tell me why is it that Spaniards, when they’re about to go into battle, invoke St James the Moor-Slayer and say: “St James, and close Spain!” By some chance is Spain open so that it’s necessary to close her, or what ceremony is that?’”

(…)

“With Macron and Marine Le Pen mud-wrestling for the presidency, French Muslims remain a key target. Macron is playing catch-up on a field where his opponent has all the advantages and no need to prove her credentials. For French Muslims, there is a stench of Vichy in the air, with pollution levels highest in cities and regions dominated by the far right. Few are searching for antidotes to this poison, but some exist. One of them is this biography.”

Read the essay here.

Reading a biography of Muhammed as a way of fighting Islamophobia, it’s a highly unusual tactic. It might work.

Nothing is ever told in passing. Or: whenever something is supposedly told in passing, pay attention.

As to Muhammed, “a simple messenger, not a maker of miracles.” That’s what an author strives for.