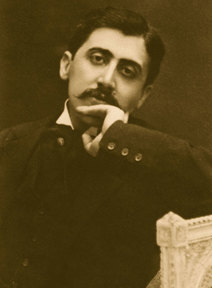

On sex rats – Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker:

‘The story of Proust and the sex rats comes in several distinct versions, in itself a marker either of multiple confirmation or of the processes of fable-making. It seems to have made its first public appearance, at least in the English-speaking world, in George Painter’s once “definitive” biography. It occurs in this form: “The wretched creatures were pierced with hatpins or beaten with sticks, while Proust looked on,” according to André Gide, because of his “desire to conjoin the most disparate sensations and emotions for the purposes of orgasm.” Painter sources the story to several different, though not necessarily independent, informants, including, in addition to Gide, the writer Maurice Sachs, who was said to have heard it from Albert Le Cuziat, the owner of a brothel Proust was known to frequent.

In the newer biography by William C. Carter, and then in greater detail in Carter’s 2006 book, “Proust in Love,” the story is repeated in more gruesome form, starting again with Proust in a brothel: “If Proust failed to achieve orgasm [from gazing at a male sex worker] ‘he would make a gesture for me to leave’ and Albert would bring in two cages,’ each of which contained a famished rat. Le Cuziat would set the cages together and open the door. The two starving beasts would attack each other, making piercing squeaks as they clawed and bit each other, a spectacle that allowed Proust to achieve orgasm.”’

(…)

‘The story then seems to have entered the cultural mainstream when it was significantly amplified in two improbable places—stranger bedfellows in the dissemination of literary gossip are hard to imagine. The first is Nabokov’s immense, bizarre 1969 novel, “Ada, or Ardor,” in which, among much other material, there is a reference to Proust decapitating rats: “crusty Proust who liked to decapitate rats when he did not feel like sleeping”—the decapitation being a neat, Nabokovian twist not previously encountered in the literature.

Meanwhile, in Albert Goldman’s best-selling, and once notorious, 1981 biography of Elvis Presley, the story occurs again, as a thing widely known, in the course of Goldman’s discussion of Elvis’s paraphilia—reported presumably by Elvis’s own André Gide, his assistant Lamar Fike, who seems to have been Goldman’s informant on Elvis’s erotic life—which allegedly tended toward movies showing “cat fights,” i.e., half-dressed women wrestling. Goldman—a former professor at Columbia, whose descent into gossipy pop bios should not detract from the intelligence or the excellence of his biography of Lenny Bruce—used the Proust story to make the point that “mama’s boys,” as they were then known (a class that included both Proust and Elvis), might work out their ambivalent feelings about their beloved mothers in sexual play-acting. Proust’s rats were an oddly recherché literary reference for a mass-market pop biography—but that, of course, was rather the point.’

(…)

‘It seems unlikely that the rat scene could quite have taken place as described. Who would keep starved rats on the premises in case a client so disposed came in? (Even a favored one, as Proust presumably would have been.) Who cared for the rats while waiting for Proust, or some other rat fetishist, to show up? Though finding rats in Paris then was no more difficult than it is now, the idea of caging fierce and starving rats for an indefinite period in anticipation of a client with this brutal taste seems improbable. The improbability of the enterprise does not make it impossible, of course—but it does remind one of how easily we suspend normal skepticism about events when they touch on venomous gossip about the well known. (And, as Benjamin Taylor suggests in his Proust book, one’s sympathies must extend first to the rats who would surely have wanted to be excluded from this narrative.)

One need hardly mention here—yet one will—the once famous and not entirely dissimilar rumor that had a movie star going to a Los Angeles hospital to have a gerbil removed from his anatomy, where it had been lodged for erotic pleasure. The inherent absurdity of this story did not keep it from becoming surprisingly widespread and, if not universally credited, then, at least, as the Web site Snopes tells us, leading “countless doctors and nurses [to] claim to have participated in, been on hand during, or heard from a reliable colleague about, the procedure.” Not only is the story false but the entire “practice” of gerbil stuffing seems wholly invented, a deliberate attempt to suggest the most improbable possible activity in order to shock and titillate readers.’

(…)

‘There is no anecdote more famous from Proust’s period than the one that has Alfred Dreyfus, on his release and rehabilitation after being falsely accused of treason, attending a dinner party and hearing a rumor about some couple’s love affair. “Well,” said Dreyfus sapiently, “What I say is: where there’s smoke, there’s fire.” That the man whose life had very nearly been destroyed—had been destroyed, had he not been resurrected—by pure salvos of smoke with no fire at all beneath would repeat this bourgeois truth is depressing. Even those who themselves have been victims of malicious gossip are prepared to credit instantly, not to say insensibly, nasty stories about their fellow-creatures. As another American writer, J. D. Salinger—himself the object and victim of a malicious rumor or two—once wrote, where there’s smoke there is often merely strawberry Jell-O. Skepticism about scandalous stories and a broadened empathy for human strangeness—not to mention, of course, compassion for the dumb beasts drawn into both—are essential to extending humanism. It was that kind of humanism that rescued Dreyfus from injustice—a cause, and of this we can be sure, that Proust championed at some risk and with great integrity.

And, of course, the story about Colonel Dreyfus and the dinner party is almost certainly a complete fabrication, composed to illustrate exactly the above irony. Which may be the occasion for another spiralling sidebar.’

Read the article here.

Perversity is our core business but we should not overdo it.

The dead are not immune to venomous gossip, for that reason I’m delighted that Gopnik came forward to defend Proust against malicious rumors.

And yes, death and eroticism are connected but not all our fantasies should become reality. I for one prefer to leave rats out my sex life, for the time being at least.