On Celan – Michael Wood in LRB:

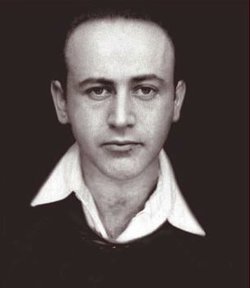

“Paul Celan was born in 1920 and died in 1970. The symmetry of these dates, arranged around the end of the Second World War, seems cruelly freighted, as does the fact that Celan chose to end his life on Hitler’s birthday. Celan – he gave himself the name by inverting the order of the syllables of his original surname, Antschel – grew up in Czernowitz, then part of Romania, now part of Ukraine. During the war he worked in forced labour camps in Czernowitz, and was released in 1944 when the Soviet army advanced into Romania. Both his parents had also been sent to labour camps in 1942, along with all the other Jews in Bukovina. His father died of typhus, his mother was killed because she was no longer healthy enough to work. The German language, Celan often said, was his mother’s tongue and the tongue of her murderers (‘Muttersprache und Mördersprache’). Writing poetry in German was for him both an act of remembrance and a rescue mission, as if a language could and could not be saved from its historical contamination.”

(…)

“Daive was 25 when he met Celan, who was then 45, and both of them can be quite sententious in their search for aphoristic wisdom (‘a poet is a pirate’; ‘the world is a theorem that nobody wants to prove any more’). But there is a moment when both men appreciate the comic mischief of chance. They are walking down the boulevard Saint-Michel, and Celan has bought an issue of Die Zeit – he likes to keep up with German culture. He doesn’t need all the sections of the fat paper, though, and ‘feverishly’, Daive says, disposes of many of them as he walks, keeping only the literary pages. These he puts in his pocket. The two flâneurs take a bus to the place de l’Opéra, and as they step off the bus and onto the pavement, Celan finds a complete copy of Die Zeit at his feet. ‘You see’, he says, ‘this happens to me with everything, every day.’ There are all kinds of ways of reading this little allegory. The powers that be don’t like minimalism. Celan’s dream of getting rid of clutter, in life as in poetry, is a lost cause. Or more optimistically, concision in poetry is fine but you can’t expect the world to play along. Celan himself makes this point elsewhere by adapting (in the wrong direction) Hamlet’s ironic remark about his father’s funeral and his mother’s speedy wedding, the fact that ‘the funeral baked meats/Did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables’. ‘Thrift, thrift, Horatio,’ he says. In Celan, this becomes ‘Counter-economy, Horatio.’”

(…)

“Microliths gathers together Celan’s hitherto uncollected prose: aphorisms, drafts for stories and plays, fragments of poetic theory, unsent letters, interviews. There are wonderful allusive jokes here (‘There’s something rotten in the state of D-Mark’), but there is also a sense of doom: ‘My Judaism: what I still recognise among the ruins of my existence.’ Celan writes this phrase in French. And there are subtle remarks that connect his poetry to what he imagines poetry more generally to be.

[Poetry is] that which, striving for truth, wants to come into language.

I don’t, in fact, write for the dead, but for the living – though of course for those who know that the dead too exist.

In the poem ... the said remains unsaid as long as the one who reads it will not let it be said to him.

And most intriguing, perhaps: ‘There is no word that, once said, does not carry with it a figurative meaning; in the poem the words believe themselves not to carry that meaning.’

There are some interesting glosses too on Adorno’s famous claim that to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. One of the meanings of this much misunderstood proposition is that it is barbaric to pretend to be civilised when everything you do shows you are not. This is close to Celan’s suggestion that ‘he who mythifies after Auschwitz is a murderer.’ Another meaning is that poetry is answerable to history, and that to write poetry as if nothing had happened is to cover up all kinds of horrors. Celan brings a curious wit and precision to this argument, noting ‘the arrogance of the one who dares ... to poetically describe Auschwitz from the nightingale – or lark – perspective’. He also writes of what happens ‘where the lyrical I goes to the objects to caress them with language’. There may be charm in such work, he says, but it will necessarily ‘lack ... the greatness of true downfalls’. He is not thinking specifically about Auschwitz, but the connection is easily made. A great deal of lyric poetry, especially of the civilised-barbaric kind, doesn’t know how to do anything but caress. Pierre Joris quotes Celan as saying something similar in relation to ‘euphony’ in poetry, ‘which more or less blithely continued to sound alongside the greatest horrors’.”

(…)

“The books brought together in the new volume are Mohn und Gedächtnis/Poppy and Memory (1952), Von Schwelle zu Schwelle/Threshold to Threshold (1955), Sprachgitter/Speechgrille (1959), Die Niemandsrose/NoOnesRose (1963). The first of these includes most of the poems Celan published in 1948, in a volume he later withdrew from circulation because of its many misprints. It contained his most famous poem, ‘Deathfugue’, first published in a journal in 1947. Much later, Celan said he was ‘far away’ from that poem, and insisted, whenever it was reprinted, on its being separated from other works by a blank page before and after. In the same interview, in 1969, he also said that he ‘rarely’ read it in public any more. It’s worth pausing over these comments, because we can respect his sense of things without letting the extraordinary qualities of the poem escape us. No poet wants to be known for only one poem when he has written so many others.

The rhythm of the poem has the mood and movement of a ballad or a nursery rhyme, an ironic lightness that contrasts powerfully with its horrific content.

Black milk of morning we drink you evenings

we drink you at noon and mornings we drink you at night

we drink and we drink

we dig a grave in the air there one lies at ease

Schwarze Milch der Frühe wir trinken sie abends

wir trinken sie mittags und morgens wir trinken sie nachts

wir trinken und trinken

wir schaufeln ein Grab in den Lüften da liegt man nicht eng

It seems grotesquely comic to address the milk here. Why tell the milk it is being drunk? Does it need to know? If it knows anything it probably knows about that grave. There are interesting points of translation here. In Joris’s version, above, the camp inmates call the milk ‘you’ throughout. In other translations (by John Felstiner and Michael Hamburger, for example) and in the German text, they start by calling the milk ‘it’ and then move to ‘you’. I like the (incorrect) intimacy from the start, and confess that I had to look at several editions to find out what is happening. I initially read the ‘it’ (sie) as a polite ‘you’ (Sie) – all it takes is a capital letter (which isn’t there). And of course if you heard the poem without seeing a text, there would be no difference.

The poem continues:

A man lives in the house he plays with the snakes he writes

he writes when it darkens to Deutschland your golden hair Margarete

he writes and steps in front of his house and the stars glisten and he whistles his dogs to come

he whistles his jews to appear let a grave be dug in the earth

he commands us play up for the dance

Ein Mann wohnt im Haus der spielt mit den Schlangen der schreibt

der schreibt wenn es dunkelt nach Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete

er schreibt es und tritt vor das Haus und es blitzen die Sterne er pfeift seine Rüden herbei er pfeift seine Juden hervor läßt schaufeln ein Grab in der Erde

er befiehlt uns spielt auf nun zum Tanz

This is not so comic, and the equation of dogs and Jews is ugly, but the pace is still jaunty. We move very quickly through various assertions and juxtapositions. The placing of the fading light suggests we are somewhere to the east of Germany, where Margarete presumably resides. In the next stanza the poem invokes another woman, Shulamith, first heard of in The Song of Songs, and whose hair is ‘ashen’, not golden. She has no association with Goethe’s Faust or with German fantasies of blonde beauty. Her later avatar would be just the woman the man who writes is not thinking of – unless he remembers her as an inmate of the camp.

The German critic Hans Egon Holthusen saw what was ‘light’ about the style of the poem, since he used that word, but went on to associate the effect with ‘a dreamy surrealism already beyond language’, and an ability to ‘escape the bloody chambers of horror of history and rise up into the ether of pure poetry’. I would like to think that most readers feel exactly the opposite – that the remorseless levity of the verse makes the bloody chambers of history all too present – but who knows, and Celan himself certainly turned away from such ironies.”

(…)

“Celan told the poet Ingeborg Bachmann that the poem was ‘a tombstone epigraph and a tombstone ... My mother too has only this grave.’ In many modern cases, counter to older traditions, graves in the earth are anonymous and collective, while graves in the air are individual and named – that’s why it’s so ironic that the poem should call a grave in the air the snakeman’s ‘gift’. There is a moving continuation of this thought in the later poem ‘Cenotaph’, where Joris’s note tells us that the two Greek words that make up the word for the memorial mean ‘empty’ and ‘tomb’. The poem says: ‘He who was supposed to lie here, lies/nowhere.’ The German doesn’t have the interesting pun on ‘lies’.

It does remind us, though, that lying nowhere, in ‘Deathfugue’, is lying at ease. ‘Da liegt man nicht eng,’ literally, ‘one doesn’t lie in a narrow space.’ If one is buried in the air, one has all the room absence and imagination can confer. And eng, ‘narrow’, is the key word in what Joris calls a ‘rewriting’ of ‘Deathfugue’. This is a poem Daive translated into French; indeed he speaks of working on it ‘side by side’ with Celan in a café. It is also fairly long, one of the strange exceptions to what I said earlier about Celan’s poems getting shorter with time. It is called ‘Engführung’, literally ‘narrow-leading’ or ‘leading in to the narrow’, and was written between July 1957 and November 1958. Celan chose the musical term stretto for the French translation and Joris follows suit. The reference is to the subject of a fugue being repeated before the first statement of it has finished; the poem notably offers almost no space for irony or evasion.”

(…)

“This poem is the last piece in a volume called Sprachgitter, and that name helps us quite a bit, even if it does contain a metaphor. A Gitter is a grid or grating or lattice or mesh; a street gutter, railings, a cooking grill, the bars of a cage. It is what we see language through, or perhaps it simply is language. Celan himself says that at this point in his career (it was 1957) ‘the difficulty of all speaking (to one another) and at the same time the structure of that speaking is what counts’.

Slanted, in the iron socket

the smouldering splinter.

By its light-sense

You guess the soul.

‘We are strangers’, the short poem called ‘Sprachgitter’ asserts. We are ‘mouthfuls of silence’ even when we speak, especially when we speak. But there is that light between the bars, and there is that guess. If we start as modestly, as unfiguratively, as possible, we may after all get somewhere, find some snowy connection between ourselves and others.”

Read the essay here.

Let’s start with Adorno. Poor Adorno, reduced to poetry and Auschwitz once again. Not mentioned is also that he retracted his dictum.

I do believe that we should not reduce Celan to the all too uplifting sermon that we are all connected, that we can find a ‘snowy connection between ourselves and others.’ Even though I appreciate the idea of a snowy connection.

Bachmann is mentioned, but unfortunately the letters between her and Celan are left out. They are worth reading and shed some light on the complicated lives of the poets. (Hint: the war is a lot but not everything.)

And is it really ‘grotesquely comic’ to address the milk?

Has poetry not been known for the habit of giving life to lifeless objects? In poetry a cupboard can have a soul, milk can be addressed. Talking to milk is not by definition more absurd than talking to a young baby. Also outside the world of poetry.

We tend to animate things all the time.

Tomorrow more Celan.