On Ghani’s last days in Kabul – Steve Coll and Adam Entous In The New Yorker:

‘On June 23rd, Ghani and his advisers boarded a chartered Kam Air jet that would take them from Kabul to Washington, D.C., to meet with Biden. As the plane flew above the Atlantic, they sat on the cabin floor reviewing talking points for the meeting. The Afghan officials knew that Biden regarded their government as hopelessly fractious and ineffective. Still, Ghani recommended that they present “one message to the Americans” of resilient unity, which might persuade the U.S. to give them more support in their ongoing war with the Taliban. Amrullah Saleh, the First Vice-President, who said that he felt “backstabbed” by Biden’s decision to withdraw, reluctantly agreed to “stick to a rosy narrative.” Biden welcomed Ghani and his top aides to the Oval Office on the afternoon of June 25th. “We’re not walking away,” Biden told Ghani. He pulled from his shirt pocket a schedule card on which he’d written the number of American lives lost in Afghanistan and Iraq since 9/11, and showed it to Ghani. “I appreciate the American sacrifices,” Ghani said. Then he explained, “Our goal for the next six months is to stabilize the situation,” and described the circumstances in Afghanistan as a “Lincoln moment.”’

(…)

‘While Ghani and his aides met with Biden, Shaharzad Akbar, the chair of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, conferred in Washington with Americans working in human rights, democracy, and development. She recalled being stunned to hear that many of the Americans had already “concluded that Afghanistan was a lost cause, and had sort of made peace with themselves.” They asked her what contingency plans she was making to flee Kabul and go into exile. After the official visit, she stayed in the U.S. through July 4th, and listened to Biden’s speech marking the holiday, in which he said, “We’re about to see our brightest future.”’

(…)

‘In February, 2020, the U.S. and the Taliban signed an accord called the Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan: the U.S. pledged to pull out all its combat troops by May of 2021 if the Taliban repudiated Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups, entered into good-faith talks with the Islamic Republic, and sought to reduce violence in the country. The Taliban also promised not to attack U.S. and nato troops who were preparing to leave. They could continue to attack Afghan forces, however. Many of the provisions were not made public, and the Islamic Republic was not a party to the agreement.’

(…)

‘The first serious attempt to negotiate with the Taliban began in November, 2010. Nine years earlier, the U.S. had overthrown the Taliban’s government, which had harbored the Al Qaeda terrorists who were responsible for the 9/11 attacks. The Taliban had mounted an insurgency to try to return to power, and Richard Holbrooke, Obama’s envoy to the region, hoped to persuade them to stop fighting and to enter Afghan politics. American diplomats and Taliban negotiators engaged in talks about a possible peace settlement. But the Taliban refused to work with the Afghan President, Hamid Karzai—the country’s first-ever democratically elected head of state—seeing him as an illegitimate puppet. Karzai, in turn, objected to America’s conferring legitimacy on extremist rebels bent on overthrowing his government.

“You betrayed me!” Karzai shouted at Ryan Crocker, the U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan, during a meeting in late 2011. Obama ultimately deferred to Karzai, and by mid-2013 serious discussions with the Taliban about power sharing had ended. Before Obama left office, he drastically reduced the U.S. troop presence in Afghanistan from its peak of about a hundred thousand. But he left eighty-four hundred American soldiers on a mission of indefinite duration, to strike Al Qaeda and a branch of the Islamic State, and to aid Afghan forces fighting the Taliban.

In 2017, President Trump appointed General H. R. McMaster as national-security adviser. McMaster recommended more U.S. airpower and intelligence aid to support Afghan forces, and a tougher approach to Pakistan, the Taliban’s historical protectors. Trump agreed to the strategy, and seemed to accept that peace between the Taliban and the Islamic Republic might not be achievable. “Nobody knows if or when that will ever happen,” he said that August. He promised that U.S. troops would remain in Afghanistan until they had defeated Al Qaeda and the Islamic State. “The consequences of a rapid exit are both predictable and unacceptable,” he said.’

(…)

‘Crocker said, adding that Khalilzad reminded him of “a Freya Stark version of an Arab proverb: ‘It is good to know the truth and speak it, but it is better to know the truth and speak of palm trees.’ ” According to Bolton, Trump once remarked of Khalilzad, “I hear he’s a con man, although you need a con man for this.” Khalilzad brushed off such insults, citing an adage often attributed to Harry S. Truman: “If you want a friend in Washington, get a dog.”’

(…)

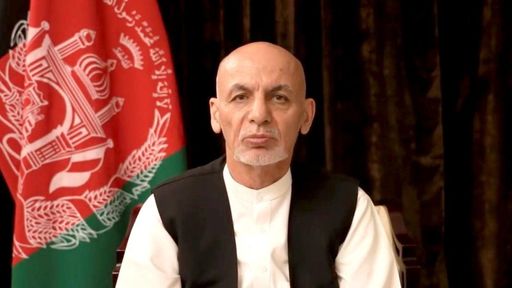

‘Ghani earned a doctorate in anthropology at Columbia, and he sometimes seemed to approach his Presidency as if it were graduate school. Between his two residences in Kabul, he cumulatively maintained a personal library of about seven thousand books, and during meetings he often referenced academic literature. He sought to empower those whom he referred to as Afghanistan’s “stakeholders”—human-rights activists, Islamic scholars, media companies, and businesses. He populated his wartime administration with other technocrats who had graduate degrees from universities abroad, and spurned traditional Afghan politicians and strongmen, who he thought had brought the country to ruin. American diplomats and military commanders continually pressed Ghani to align with Karzai, Abdullah, and figures such as Abdul Rashid Dostum, who had an armed following and a record of alleged human-rights abuses. Much of the strength of the military opposition to the Taliban resided with such individuals, and it was hard to see how Ghani could strike a deal without them.

“He’s just not a good politician,” James Cunningham, who served as the U.S. Ambassador in Kabul during Ghani’s first term, said. “There are lots of things I do admire about him, but he wasn’t able to find the political skills necessary to build coalitions and partnerships with people who disagreed with him.”’

(…)

‘Khalilzad and Pompeo saw Baradar’s role in Doha as a sign that the Taliban were serious about the talks. (As Pompeo once told Ghani, Baradar is “a very sophisticated player.”) The day after their lunch, Khalilzad joined Baradar in his hotel room, which overlooked a swimming pool where women were lounging in bikinis. “You must feel like you’re in Heaven,” Khalilzad joked, invoking the commonly held Islamic belief that the afterlife offers a paradise of water and virgins. Baradar walked to the window and pulled the curtain shut.’

(…)

‘The Taliban envoys insisted that they needed the concession to convince their most hard-line factions of the benefits of peace talks. Khalilzad said that the U.S. would try to persuade Ghani to agree to this, and when U.S. military officers in the room realized that the Taliban might get their prisoners without the Americans getting a ceasefire, they wanted to walk out, Andru Wall, a Navy commander at Resolute Support, recalled. Khalilzad “plainly wanted a deal and seemed willing to give the Taliban almost everything,” Wall said. “It was not clear if we had any true red lines.” On July 3rd, the draft agreement was updated to include the release of “up to” five thousand Taliban prisoners. (In return, the Taliban would release a thousand Afghan government detainees.)’

(…)

‘The proposal was a prescription for confusion and further conflict. Both sides accepted that the U.S. would no longer engage in “offensive” operations against the Taliban. But the U.S. and the Taliban disagreed about the circumstances in which the U.S. could come to the defense of its allies. The Taliban argued that Miller’s forces could strike only guerrillas who were directly involved in attacks on Afghan forces, whereas Miller considered this interpretation too narrow, and concluded that he was also allowed to act in other ways, including striking preëmptively against Taliban fighters who were planning an attack.

Either way, the U.S. concessions to the Taliban would clearly be a blow to Ghani’s military. For years, Afghan forces had relied on U.S. bombers and artillery to back up their ground attacks, and to strike Taliban encampments and supply lines. Now Afghan troops would be on their own during offensive campaigns, and, if they were attacked, they would face uncertainties about whether or when U.S. forces would go into action.’

(…)

‘Since 2015, fewer than a dozen American soldiers had died annually in combat in Afghanistan. The yearly death toll suffered by the Islamic Republic’s soldiers and police was estimated at more than eight thousand. According to the United Nations, the war also claimed the lives of several thousand civilians each year.

At the end of August, Trump came up with a plan to invite the Taliban to Camp David to sign the agreement. Then, on September 5th, a car bomb detonated in Kabul, killing about a dozen people, including Elis Angel Barreto Ortiz, a thirty-four-year-old U.S. Army sergeant. That weekend, Trump ended the peace talks with a tweet blaming the deaths on the Taliban: “If they cannot agree to a ceasefire during these very important peace talks, and would even kill 12 innocent people, then they probably don’t have the power to negotiate a meaningful agreement anyway.”

Pompeo told Khalilzad, “You should come home.”’

(…)

‘At the same time, the guerrillas mounted offensives in Kandahar and Helmand that were clearly “violations in spirit, if not the written word” of the Doha accord, Miller said. During the last three months of 2020, after the prisoner releases, violence spiked across Afghanistan, and civilian casualties rose by forty-five per cent, compared with 2019. The onslaught “exacerbated the environment of fear and paralyzed many parts of society,” the U.N. reported. The Taliban also protested many American strikes carried out in support of Afghan forces, calling them a violation of the Doha accord’s annex on managing combat. Like aggressive corporate litigators seeking to drown their opponents in paper, the guerrillas filed more than sixteen hundred complaints to Khalilzad’s team, and used them to justify their intensifying military campaign against Kabul.’

(…)

‘In early 2021, Khalilzad and Blinken came up with a work-around. They would jump-start an “accelerated” peace process that would set aside the negotiations in Doha in order to leap to a final power-sharing deal between the Islamic Republic and the Taliban. Khalilzad helped write an eight-page draft of a so-called Afghanistan Peace Agreement, which was breathtakingly ambitious: it imagined a new constitution; a transitional government with an expanded parliament, to accommodate many Taliban members; reconstituted courts; a new body, the High Council for Islamic Jurisprudence; and a national ceasefire. He hoped that the Taliban and the Islamic Republic would agree to attend a peace summit in Turkey.

On March 22nd, Blinken met with nato foreign ministers, who insisted that the U.S. should be doing more to try to forge a political settlement in Afghanistan. Blinken called Biden and said that he wanted to explore whether a troop withdrawal could be delayed until after the summit in Turkey, even though the Taliban had not yet agreed to participate. This would show nato allies that the U.S. was listening, Blinken argued, but it would also mean breaking the Doha agreement.

Khalilzad met with the Taliban and argued that, if they wanted Afghanistan to enjoy international aid and recognition, they should accept a delay in the U.S. withdrawal so that a power-sharing agreement could be negotiated in Turkey. When Taliban negotiators observed that the Americans were talking about breaking the Doha accord, they did not directly threaten to renew attacks against U.S. and nato forces. But they made clear that “bad things would happen,” a State Department official involved said.

On April 5th, Jon Finer, Biden’s deputy national-security adviser, called Mohib and said it was unlikely that the U.S. would withdraw from Afghanistan before May 1st. But any extension, he said, would be “for a limited time.” The White House continued to hope that talks with the Taliban might ease the transition. “It’s important that the Afghan government speak with one voice,” support the peace process “unambiguously,” and adopt a “constructive and mindful attitude” toward talks with the Taliban, Finer said. Mohib shared the news with Ghani: the American era in Afghanistan would end soon.’

(…)

‘A senior State Department official involved said that by June “you could see there wasn’t going to be anything there” to keep Afghan aircraft flying. Maintenance aside, the essential problem, according to a senior Defense Department official, was that “we were leaving.” The entire Afghan military was designed to operate around U.S. systems and expertise, and when that was gone the Afghan forces unravelled.’

(…)

‘ Last summer, Bismillah Khan reported that the Taliban were offering Islamic Republic soldiers money, and a letter of passage, to protect them from harassment after they surrendered and went home. By August, “money was changing hands at a rapid rate,” a senior British military officer said, with Afghan security forces getting “bought off by the Taliban.” For weeks, the U.S. and its European allies had tried to avoid evacuating their personnel or Afghans who worked for them, for fear that this would look like a rush to the exits, but by early August the British military had evacuated an Afghan intelligence outfit that intercepted communications by the Taliban. Provincial capitals now toppled one after another; on August 12th, Ghazni fell. That evening, Blinken and Lloyd Austin, Biden’s Secretary of Defense, called Ghani to inform him that three thousand U.S. troops would fly in to seize the Kabul airport. The troops were not being sent to defend Kabul against a Taliban assault; they were meant to protect evacuating American personnel. The next day, the Taliban took the major cities of Kandahar and Herat. Dostum, under siege, left the country for Uzbekistan, as did Ata Mohammad Noor, another powerful and independent leader in the north.’

(…)

‘He told Blinken that he was ready to accept whatever his envoys and the Biden Administration agreed on with the Taliban. Blinken asked him to “get the delegation to Doha” as quickly as possible, “to show the Taliban this is a serious process. We need a ceasefire to process this.” “Please lean as much as you can on a dignified process,” Ghani said. He remained adamant that any transfer of power should be endorsed by the Afghan assembly. “Please convey to the Taliban that this is not a surrender.” “Dignified is exactly what we want as well,” Blinken said.’

(…)

‘Mohib belonged to a Signal group chat that included some of the country’s top intelligence and security officials. On the night of the fourteenth, bad news poured across the channel. Nangarhar had fallen to the Taliban, as had several other provinces. On Sunday morning, the fifteenth, Mohib walked from his official residence to Ghani’s office, for their daily staff meeting, at nine o’clock. The channel now reported that members of the Taliban had reached Kabul. The gunmen might be local Taliban who had decided to show themselves, they might be criminals posing as Taliban, or they might be the vanguard of an invasion force. There were also many reports that Kabul policemen, soldiers, and guards were taking off their uniforms and going home.

In Doha that morning, Khalilzad recalled, he met Baradar at the Ritz-Carlton. During their discussion, Baradar “agreed that they will not enter Kabul” and would withdraw what Baradar described as “some hundreds” of Taliban who had already entered the capital. Based on Ghani’s concessions the previous day, Khalilzad hoped to arrange a two-week ceasefire and an orderly transfer of power in Kabul, to be sanctified by a “mini loya jirga.” Khalilzad was in WhatsApp contact with Abdul Salam Rahimi, an aide to Ghani, and informed Rahimi of this plan. Rahimi told Ghani that the Taliban had pledged not to enter Kabul. Yet this was based on assurances from Khalilzad and the Taliban, and Ghani regarded both as unreliable sources.’

(…)

‘Mohib doubted that all of Ghani’s bodyguards would remain loyal if the Taliban entered the palace grounds, and Kochai indicated that he did not have the means to protect the President. Mohib helped Rula onto the President’s helicopter and asked her to wait. With Kochai, he drove back to the residence.

He found Ghani standing inside and took his hand. “Mr. President, it’s time,” Mohib said. “We must go.”

Ghani wanted to go upstairs to collect some belongings, but Mohib worried that every minute they delayed they risked touching off a panic and a revolt by armed guards. Ghani climbed into a car, without so much as his passport.

At the helipad, staff and bodyguards scuffled and shouted over who would fly. The pilots said that each helicopter could carry only six passengers. Along with Ghani, Rula, and Mohib, nine other officials squeezed aboard, as did members of Ghani’s security detail. Dozens of other Arg palace staffers—including Rahimi, who was still talking with Khalilzad about a ceasefire, and had no idea where Ghani or Mohib had gone—were left behind.

At about two-thirty, the pilots started the engines. The three Mi-17s lifted slowly above the gardens of the palace, banked north, and flew over Kabul’s rooftops toward the Salang Pass and, beyond that, to the Amu Darya River and Uzbekistan.’

Read the article here.

I supported Biden’s decision to leave Afghanistan, I still do, but after reading more about the history of the negotiations between the Taliban and the US it’s tempting to think that at least some inside the Trump government wanted the Taliban back in Afghanistan.

But the conspiracy theory is just the explanation of sheer incompetence.

And Ghani’s haughtiness, his unwillingness to understand power games, his anger, all this made matters worse.

The incompetence of American diplomacy made the Taliban look like geniuses.