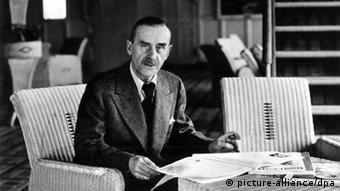

On Mann – Michael Lipkin in TLS:

‘Among his many accomplishments, Thomas Mann can count one of the most famous about-faces in literature. In 1914, at the age of thirty-nine, Mann published “Thoughts in Wartime” (“Gedanken im Kriege”) in Die neue Rundschau, voicing his enthusiasm not just for the German cause in the First World War, but for the war itself. The essay’s vehement rejection of democracy shocked his admirers, who knew him as a writer who chronicled – all but luxuriated in – the decadence and decline of his culture, and endeared him to the nationalist right. Four demoralizing years of trench warfare later, Mann doubled down with Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen), a 500-page tract asserting Germany’s rights to defend itself against the aggressions of English and French “civilization”.

In 1922, however, amid the unemployment, inflation, assassinations, and violent political street fights of the Weimar Republic, Mann re-established himself as a defender of the fledgling democracy with “On the German Republic” (“Von deutscher Republik”). This successful reputational whitewashing, followed by the rapturous reception of The Magic Mountain (1927; Der Zauberberg, 1924), helped him to win the Nobel prize for literature in 1929. Mann was abroad on the lecture circuit when Hitler rose to power in 1933. He wisely elected to stay there; at home, his books were kindling for the burnings on Unter den Linden. He famously spent his last active years in California, of all places, testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee as a suspected Communist.’

(…)

‘It would be a mistake, however, to attribute this highly selective rewriting of German cultural history to sibling rivalry entirely. Reflections also addressed a problem that would come to define European modernism in the decades to come. By the time of the First World War, German high culture had become increasingly democratized by new forms of mass media, and the then-distinctive values of the upper classes – those of diligence, morality, and renunciation – had eroded (as Mann depicts so vividly in Buddenbrooks, his novel of multi-generational bourgeois decline). The young Mann identified with the figure of the genius, but that figure only made sense in the light of the bourgeois culture from which he had emerged. Art, for Mann, was meant to offer something that stands in dialectic opposition to the social world, and so little space was left for the artist who wanted to resist being swallowed by homogeneity. Mann felt that, as a German, he was lucky – he needed only to look back to the literature and culture of the nineteenth century, to the works of Theodor Storm, Adalbert Stifter and Theodor Fontane.’

Read the article here.

The bourgeois has been always in decline, the middle class came into being somewhere in the 19th century and started its decline right away. Read Peter Gay’s excellent book ‘Schnitzler's Century: The Making of Middle Class Culture’.

But the idea of the ‘genius’ and the belief in this idea did slightly better than the bourgeoisie itself, even though it was produced in the womb of the middle class.

So did the idea that art would save us, although this idea made a come-back in the appearance of activism that names itself art.

The best excuse for being and almost everything related to being: we are here to make the world a better place.

We are here to help you.