On demands and grievances – Stephen Kotkin in TLS:

‘Vladimir Putin is no Hitler. True, he forcibly annexed his Sudetenland equivalent, the predominantly ethnic Russian Crimea, and depicted this action as an exercise in self-determination. And he continued to rail against Ukraine as an artificial state, asserting that Russians and Ukrainians were “one people”, even as he baselessly charged Ukraine with genocide against ethnic Russians in Ukraine’s Donbas, where he sponsored armed separatists. He backed cyberattacks and other subversion and, beginning in late 2021, surrounded Ukraine with an immense invasion force, stationing troops in Belarus, and consolidating his hold over that country, too. He had his foreign ministry publish two draft treaties – ultimatums, for Washington and for NATO – to codify his demands, beginning with his most important one – “no more NATO expansion eastwards and especially not for Ukraine” – and extending to a total rollback of NATO deployments to all members admitted after 1997. He also called for a ban on certain weapons in Europe that he deemed a threat to Russia’s heartland. Unlike Hitler, however, Putin does not aim for conquest of the continent, and he would have been over the moon if the West had granted his demands without him having to wage war.’

(…)

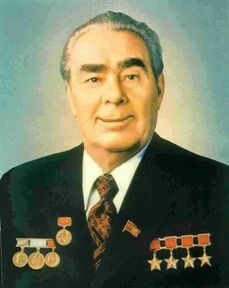

‘Renewed hostilities invite re-examination of the Cold War, and we now have the first Leonid Brezhnev biography, translated from the German, based on an impressive array of declassified Soviet sources. The initial point of entry of the author, Susanne Schattenberg, was her appointment as director of a Soviet dissident archive in Bremen. “I expected to be working on a Stalinist, a hardliner, an architect of domestic and foreign policies of repression”, she confesses. “To my surprise, I quickly realized that this was too simplistic a picture. Brezhnev left the dissidents to the KGB chiefs, [Alexander] Dubček was his protégé, not his enemy.” She adds: “Instead of a dogmatic ideologue, a heart-throb who loved fast cars and liked to crack jokes. I will not escape accusations of being something of a Brezhnev apologist”.’

(…)

‘All the wink-wink revisionism implodes as Schattenberg recounts what transpired under the Thespian’s eighteen-year rule. A notorious self-dealer, Brezhnev failed to tackle spiralling corruption seriously, and discontinued the rotation of cadres around the Union, allowing unaccountable political machines and proto-oligarchic industrial interests to entrench themselves. He accepted more than 200 awards for imaginary achievements, including the military rank of marshal. He pretended to level social hierarchies, hunting and playing dominoes with his bodyguards, cooks and drivers, when state affairs beckoned. His regime wasted a fortune trying to fix productivity in collectivized agriculture, and failed to establish a vital stabilization fund from the windfall of hard currency earnings delivered by the global oil shock. He coveted the company of Willy Brandt, Georges Pompidou and Richard Nixon, wept about preserving the peace, then approved the invasion of Afghanistan, undermining Ostpolitik and détente.’

(…)

‘Zubok dismisses nearly the entire corpus of writings on the Soviet collapse, yet almost all his arguments ring a bell – although he omits the one about how Gorbachev’s temporizing averted Armageddon. Hardliners, Zubok argues redolently, proved too hapless to remove Gorbachev in time to halt his unwitting liquidation of the system. But Zubok further avers, as those hardliners did at the time, that the Soviet leader should have overthrown his own reformist self. The author perceives a grand opportunity in February–March 1990, when Gorbachev could have imposed “presidential rule”, rolled back the rights of the Soviet republics, and forced through the “radical” market reforms of his adviser, Nikolai Petrakov. “It would have been a huge gamble, but it was still feasible and could have changed the climate in the whole country”, the author asserts. How a committed anti-capitalist with democratizing tendencies could have become the opposite of himself remains unclear. Gorbachev did gesture in the hardline direction, but hesitantly, and, Zubok writes, “the window of opportunity closed: 1990 continued and ended as the year of wasted opportunities”.’

(…)

‘Vladimir Putin has become his own historian. In his mind, Moscow initiated and partnered in the end of the Cold War standoff, which the West treated as its victory and Russia’s defeat. A chorus of Western officials, including former US Secretary of State James Baker, verbally promised in 1990–91 not to expand NATO into former Warsaw Pact or former Soviet republics, and then did just that. From 1999 Putin personally absorbed four rounds of NATO eastward expansion as well as a Western statement in 2008 that Ukraine and Georgia “will become members of NATO”. True, Ukraine is not (yet) in NATO – nor is Georgia – but NATO is in Ukraine: the US, the UK, Turkey and others have sent weapons and “advisers”, and the Americans opened a maritime operations facility in Ochakiv. In 2014, the US intervened to help overturn the elected government of Ukraine and install pro-Western Ukrainians, whom Putin deems Nazis (as some Second World War Ukrainian nationalists were). All of this confirms for him the view that lesser powers are not sovereign in reality, but playthings in the hands of great powers. He sprang his apocalyptic “special operation”, in his words, to “demilitarize” and “de-Nazify” Ukraine. Ukraine had become a platform for the US and NATO to project power along Russia’s southwestern flank, part of a pattern of ignoring Russia’s “security” concerns and reneging on commitments.

Enter M. E. Sarotte. Her engaging book, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the making of post-Cold War stalemate, draws its title from a conversation between Baker and Gorbachev on February 9, 1990, about German unification, and superficially appears to corroborate Putin’s case. “Baker uttered the words as a hypothetical bargain”, Sarotte recounts. “What if you let your part of Germany go, and we agree that NATO will ‘not shift one inch eastward from its present position?’” Gorbachev did not fix the verbal offer in a signed agreement, and, in his meeting the next day with West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, he bestowed an unconditional commitment to the Germans to decide their fate. Later, writes Sarotte, Gorbachev lied about these episodes because he had messed up, while Baker falsified his own memoir, drafted by his aide Andrew Carpendale, who objected to the rewriting of the record. Sarotte, along with the private National Security Archive in Washington, helped declassify many of the key documents that show a parade of Western officials suggesting, for a brief moment, limits on NATO enlargement. Despite its title, however, these vague vows are not the book’s subject. Sarotte reminds us that, in 1997, Presidents Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin signed the NATO-Russia Founding Act, fixing in writing the absence of restrictions on NATO expansion to former Warsaw Pact countries or former Soviet republics. Yeltsin had tried to secure a Russian veto over expansion but failed, although he announced at a press conference that he had succeeded.’

(…)

‘NATO expansion did not cause Putin’s regime to jail or murder journalists and opposition figures, seize and manipulate domestic media, loot state funds on an unfathomable scale, or conflate the country’s survival with that of his personal rule, any more than a defensive alliance of mostly pacifist nations, many of which spent little on their militaries until Putin galvanized them, threatened the security of Russia. But the fallacy of portraying the Kremlin’s familiar recourse to autocracy, repression, militarism and suspicion of foreigners as somehow a reaction to Western actions has a long history. Martin Sixsmith, a lifelong Russia hand and a BBC correspondent in Moscow, Brussels and Warsaw during the fateful years (1980–97), admits to having been convinced that 1991 meant “autocracy was dead in Russia, that centuries of repression would be thrown off and replaced with freedom and democracy. But I was wrong”. Like Sarotte, albeit without her sophistication, he partly blames the West, and, to underscore the point, offers a psychological take in The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War mind. Sixsmith observes, in his characteristic style of marshalling opinions rather than evidence, that “Vladimir Pechatnov, the head of the State Institute of International Relations of the Russian Foreign Ministry, says conflict might have been avoided if the West had paid more attention to Soviet sensitivities”. Stalin felt disrespected, so he went on a rampage.’

(…)

‘Failing to understand the history of how the West defended freedom goes hand in hand with all too many analysts being willing to give away other peoples’ freedom now. At Munich in 1938, the alternative to appeasement was war or genuine deterrence, meaning the credible threat of a military response and other strong measures to inhibit and, if necessary, punish and reverse Hitler’s aggression. Even as rogue leaders of powerful states are being dealt with resolutely, whether in the case of genocidal Nazi Germany or today’s gangster kleptocracy in Russia, their wider elites need to feel they have a stake in the international order, which means engaging in concerted, realistic diplomacy, too.’

Read the essay here.

Indeed, whether Bush père did or did not fulfill his promises to Gorbachev is an issue that should be interesting to historians mainly.

Grievances that are forty years old should not (always) be a valid reason to go to war now. Most grievances, except for let’s say genocide, should have an expiration date. You can compensate people, you cannot undo history,

Kotkin seems to be missing one point: diplomacy is very often giving away other people’s freedom to defend freedom.

Somebody else spoke about the ‘victims of history,’ in another era we would have called the the victims of fate.