On revolution and performance – Robert Darnton in TLS:

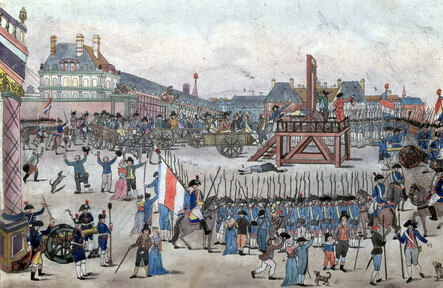

‘To be sure, the concept of theatricality can be stretched so far as to cover any interaction. The sociologist Erving Goffman uses it to study a performance element in all sorts of situations – anywhere, in fact, that an individual presents himself before others, who then become an audience. While experiencing theatricality in this fashion during their everyday lives, Parisians absorbed it from the theatres themselves. Ordinary folk – shopkeepers, artisans, clerks – attended performances along with the elite in the officially privileged theatres, the Comédie-Française and the Comédie-Italienne. For 20 sous, less than a day’s wage for a skilled worker, they crammed into the pit (parterre), which often contained more than 600 shoving, shouting and brawling spectators. While ladies and gentlemen looked down from the loges, the pit interrupted performances with catcalls, exchanged remarks with the actors, and sometimes erupted in violence. In 1751 a company of soldiers was stationed to maintain order inside each of the two official theatres. On several occasions the troops intervened to repress riots – notably on December 26, 1787, when fifty of them put down a brawl in the pit of the Comédie-Italienne. The pit exercised power. By applauding or hooting, it determined the success or failure of plays. Its antics were part of the performance, and they illustrate an argument that I would like to advance about the immediate origins of the Revolution: theatricality and violence went together.’

(…)

‘The Parlement passed a resolution protesting against the attempted arrest of its members and sent a delegation to Versailles. The king refused to see it; the session continued late into the night; and at 2 o’clock in the morning of May 6, a battalion of 200 Gardes françaises occupied the Palais while several hundred more troops surrounded it outside. The captain of the Gardes, Vincent d’Agoult, demanded entry to the Grand’Chambre and ordered the court to surrender the two magistrates. The parlementaires then rose as a body and declared “We are all d’Eprémesnil and Goislard”. After more dramatic scenes, d’Eprémesnil stepped forward, submitted to arrest, and took leave of his colleagues with a farewell speech that reduced all of them to tears. Goislard did the same.

The session finally ended after thirty hours. The public dispersed, having been locked up all night with the parlementaires and even forbidden, along with the peers of the realm, to go to the toilet unless accompanied by two guards. D’Eprémesnil and Goislard were sent to exile in remote prisons. On August 8, in a formal lit de justice (a session to force the registration of an edict) in Versailles, the king dissolved the Parlement, and his ministers announced that it would be replaced by a high court called a Cour plénière, while a new judicial system would be imposed on the entire kingdom. Although the provincial parlements would continue to exist, they and their inferior courts would be restructured and reformed, and they would lose the right to remonstrate against royal decrees.’

(…)

‘The Parlement passed a resolution protesting against the attempted arrest of its members and sent a delegation to Versailles. The king refused to see it; the session continued late into the night; and at 2 o’clock in the morning of May 6, a battalion of 200 Gardes françaises occupied the Palais while several hundred more troops surrounded it outside. The captain of the Gardes, Vincent d’Agoult, demanded entry to the Grand’Chambre and ordered the court to surrender the two magistrates. The parlementaires then rose as a body and declared “We are all d’Eprémesnil and Goislard”. After more dramatic scenes, d’Eprémesnil stepped forward, submitted to arrest, and took leave of his colleagues with a farewell speech that reduced all of them to tears. Goislard did the same.

The session finally ended after thirty hours. The public dispersed, having been locked up all night with the parlementaires and even forbidden, along with the peers of the realm, to go to the toilet unless accompanied by two guards. D’Eprémesnil and Goislard were sent to exile in remote prisons. On August 8, in a formal lit de justice (a session to force the registration of an edict) in Versailles, the king dissolved the Parlement, and his ministers announced that it would be replaced by a high court called a Cour plénière, while a new judicial system would be imposed on the entire kingdom. Although the provincial parlements would continue to exist, they and their inferior courts would be restructured and reformed, and they would lose the right to remonstrate against royal decrees.’

(…)

‘Dramas tend to touch people more intensely than books. While playing their part as the audience, spectators suspend the roles they assume outside the theatre and accept the action on the stage as immediate reality. When La Cour plénière was performed, the audience reacted in just this fashion, according to its preface: The action on the stage was so true, the illusion so complete that on repeated occasions, the spectators, forgetting they were at a play … hooted the actors playing Brienne and Lamoignon, thinking that they were jeering at the originals. Then they woke up as from a dream, stared at each other, laughed at their mistake, and made the room ring with applause.’

(…)

‘His proposals, which featured a land tax that would fall evenly on all proprietors, seemed so progressive, at least in retrospect, that one historian, in a supremely anachronistic essay, described them as “Calonne’s New Deal”. Although the Notables precipitated Calonne’s fall by opposing his reforms, Brienne and Lamoignon took over his programme and tried to force the land tax through the Parlement of Paris. When it resisted, they attempted to destroy the political power of all the parlements just as Maupeou had done. The opposition to their reforms, by the nobility and clergy as well as the parlements, was the crucial element, according to this interpretation, that set the revolutionary process in motion.

For my part, I do not think an aristocratic revolt took place in 1788, but the point that I want to stress is the disparity between contemporary experience and the historical versions of it. The vilification of Brienne and Lamoignon can be taken as a measure of that disparity. Nothing suggests that they were any more wicked than other ministers under the Ancien Régime, or wicked at all, yet the public focused on them – and some minor players such as d’Agoult – with such intensity that it lost sight of other factors in the crisis.

By casting Brienne and Lamoignon as villains, the dramaturgy of 1788 swept aside alternative ways of construing events. Yet competing views did not disappear. In fact, several of the most progressive Parisians supported the ministry and even collaborated with it. Condorcet, following a line set long ago by Voltaire, scorned the parlements as an impediment to reform, and so did other philosophes such as the abbé Morellet. The ideological landscape of France was scattered with causes and opinions. That is why the theatricality of 1788 was so decisive. By placing despotism at the centre of the stage, it obscured the view of other issues. It reduced a complex situation to the opposition between despotism and liberty.’

(…)

‘The theatricality that permeated Paris suggests that the perception of events is as important as events themselves – and, in fact, that they are inseparable. Parisians did not fail to understand reality when they took to the streets in 1788. They reconstructed it.’

Read the complete article here.

Theatricality and violence go together, yes.

Violence is a performative act.

And even when perpetrators try to hide the crime the act of violence is filled with theatrical elements. See the genocide in Rwanda. Or even the sadistic rituals in concentration camps.

January 6, 2021 in Washington DC was theater as well.

The gestures of revolution remain largely the same, just the theater is not center anymore of the reconstruction of reality. Technology made it possible to replace the theater by all sorts of screens.

The reconstruction of reality, the simplification of it is still needed to arouse the masses. Complexity is not helpful when you want to seduce the mob.