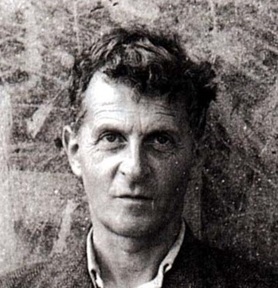

On Wittgenstein - Ian Ground in TLS:

‘On July 4, 1916, the twenty-seven-year-old Ludwig Wittgenstein, having survived direct fire from Russian artillery, picked up his notebook to write down an idea: that the meaning of the world does not lie within it but outside of it. For Wittgenstein, this strange thought was both a personal epiphany and the result of five years of consuming, torturous reflections on the nature of logic. It was a thought that eventually made its way into the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. More than 100 years after its publication, this work continues to fascinate, provoking both intense scholarly debate and the enthusiastic, if sometimes inchoate, engagement of painters, sculptors, film-makers, novelists and poets. The interest it commands lies in part in its peculiar and austerely beautiful fusion of the formal and the gnomic, the technical and the spiritual, the logical and the mystical.’

(…)

‘For the first time in English translation, we now have a bilingual text of the three extant private notebooks Wittgenstein kept between 1914 and 1916. (It is likely that he wrote three others, which are now lost). He wrote his private reflections and diary entries on the left (verso) pages of each notebook, in a simple code, and his philosophical notes, uncoded, on the right (recto) pages.’

(…)

‘For the first time in English translation, we now have a bilingual text of the three extant private notebooks Wittgenstein kept between 1914 and 1916. (It is likely that he wrote three others, which are now lost). He wrote his private reflections and diary entries on the left (verso) pages of each notebook, in a simple code, and his philosophical notes, uncoded, on the right (recto) pages.’

(…)

‘In his definitive biography of 1990, Ray Monk remarks that Wittgenstein valued love almost as a divine gift, but was uneasy, less about being homosexual and more about being a sexual being at all. Monk ventures that Wittgenstein’s sexual life took place more in his imagination than in reality, and often Wittgenstein curses himself even for that. Perloff points out that across his life, he loved three men: David Pinsent, Ben Richards and, especially, Francis Skinner. What’s worth noting here is that for all of us, not just someone as decidedly strange as Wittgenstein, our sexuality is an arena where questions, both political and personal, about responsibility and recognition, choice and chance, swirl around our sense of identity, what kind of person we are or need to be. Seen one way – the wrong way, probably, but nevertheless how Wittgenstein saw it – sexuality is a threat to a greater project, that of achieving integrity. It is possible to regard sexuality, whatever forms it takes, and indeed whether real or imagined, as an invasion of the self by brute contingency, by desires that are somehow not wholly our own. There is something about our sense of ourselves that balks at such adventitious intrusions in the soul. And seeing this connection between logic, the meaning of things and what it is to be a person is perhaps the key insight that this new translation offers into the strange confluence of the abstract and the mystical that makes the Tractatus unique.’

(…)

‘Wittgenstein had little interest in politics and hardly ever commented on the rights and wrongs or likely outcomes of the war, except to predict that Britain would win because it was, for reasons undisclosed, “better”. He talked too about “a great common cause”, but only to lament his disappointment that great causes turn out not to be ennobling. Moreover, his education and immensely wealthy background would have allowed him to enlist as an officer. Instead he joined as an infantryman. But it would be a mistake to think that Wittgenstein marched off from any sense of what might be called “duty”, as conventionally understood. His aim was clear: the war would allow him to work on himself.’

(…)

‘Knowing full well that it meant maximum exposure to enemy fire, he requested to be assigned to the observation post. “Only then”, he wrote, “will the war really begin for me … And – maybe – even life. Perhaps the nearness of death will bring me the light of life. May God enlighten me.” By some miracle he survived direct shelling, was honoured for his bravery, then endured the Austrian retreat from the Russians through the Carpathian Mountains. The last verso entry published here is from August 1916. He later survived the Russian Kerensky offensive, then, as a Leutnant (lieutenant), fought on the Italian front. He ended his war in an Italian prison camp, having been captured just one day before the armistice between Austria-Hungary and Italy came into effect.’

(…)

‘For meaningful thought and language to be possible, anything one says must be capable of being either true or false. The only necessity lies in logic, which is nothing but tautology. Logic says nothing itself, and only shows itself in the structure of what we say. If I am not thinking or saying what could be false, I am not thinking or saying anything at all. For Wittgenstein, it followed that the world itself – that about which we think and speak – is contingent, “a totality of facts”. And this includes our own identity as particular, psychological beings. We are, ourselves, “facts, not things”

But whether and how things matter – the foundationally serious in life – is not contingent. The ethical is not a matter of facts being as they are and happening as they do, but of how they ought to be and happen: in particular, how I ought to be and how I ought to live my life. But if, in taking up an ethical view of my life, I am not thinking or saying what could be false, am I thinking or saying anything meaningful at all?

Wittgenstein would come to claim that the realities of value and the ethical life – that we are ethical beings – are what the Tractatus is written to show (and not tell). Indeed, as these notebooks demonstrate, for Wittgenstein the ethical question of the kind of person one should be is the most pressing question there is. But just as the necessity of logic cannot be said, but shows itself in how we think, so the necessity of value cannot be meaningfully articulated, but can only show itself in how we live, both outwardly and within.’ Seen that way, the Tractatus is not in itself a revolution in European thought, but a last gasp. An exhalation into silence that would be seen again in the work of Pinter and Beckett.

In the verso pages Wittgenstein complains bitterly about his fellow non-officer soldiers. They are “a bunch of swine”, stupid and malicious.

9.11.14.

Just overheard a conversation between our commander and another officer. What vulgar voices! All the nastiness of the world screeches and croaks out of their mouths. Insolence wherever I look. Not a feeling heart as far as my eye can reach!!!——

Of course, we know nothing of them. They were probably conscripted from Serbia and beyond, taken from their families and farms to kill and do their best to avoid being killed. For all our fascination with Wittgenstein, it is not surprising that they resented and even bullied this high-class, aloof figure, always scribbling in his notebook, pausing only to look up and scowl at them. What did they say to each other when Wittgenstein took an extra shift at the Goplana searchlight or, in Galicia, volunteered for the observation post? Did they admire his bravery or, more likely, resent and fear the precedent being set? Perhaps for these unnamed men Wittgenstein’s unwanted company was the perfect representation of the lunatic contingency that had engulfed their lives.’

(…)

‘Philosophical Investigations is, above all, a work that bustles with humanity, sometimes wryly smiling, sometimes raging at the philosophical contempt for the ordinary. In his acceptance of the myriad practices, games and ways of speaking, and in his devotion to the details of buying apples, dancing, waiting for someone to arrive, learning to read, pointing to a colour then a shape, Wittgenstein suggests that the way to lead an ethical life is not to fight to be a particular person, but to be open to diverse forms of life. Not to seek to penetrate or explain away the illusory philosophical depths, but to embrace living deeply on the surface of things.’

Read the article here.

Twenty years ago or so I was writing a book on Otto Weininger and I immersed myself in reading Wittgenstein, a maddening adventure, I also immensely enjoyed Monk’s biography.

The mysticism of the young Wittgenstein is still seductive, and I would say it’s fairly German.

The realization that ethics is about how we live, not about talking how we should live, is a variation on something I was told in Jewish school, I must have been 8 or so.

A really wise man keeps his good deeds secret.