On the emptiness of meaning-making – Dan Piepenbring in The New Yorker:

‘The Japanese lieutenant Hiroo Onoda emerged from hiding, in 1974, after fighting the Second World War for twenty-nine years. He’d been deployed to the Philippine island of Lubang in 1944, when he was twenty-two, and had received secret orders to hold his position even as the Imperial Army withdrew from its airfield there. His commander promised that someone would come back for him eventually. When the war ended, the following summer, Onoda had no way of knowing it, and his jungle vigil continued. He was joined, at first, by three fellow-soldiers who’d got lost in the jungle during the retreat, but then one man wandered off and surrendered, and the other two were killed in skirmishes with local police. Hoping to lure Onoda out, the Japanese dropped leaflets and sent search parties. His brother spoke to him through a loudspeaker; his father left him a haiku. But Onoda had sewn himself so seamlessly into his surroundings that he eluded detection. Trained in military intelligence, he dismissed all outside communication as propaganda. In the U.S., newspapers called him a “straggler” or “holdout,” words that failed to convey the sublime futility of his mission.

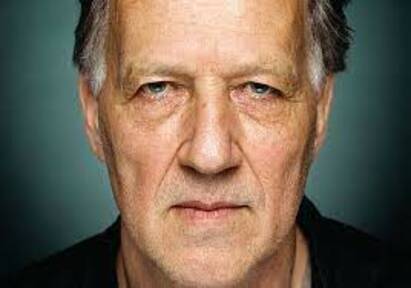

Fortunately, Werner Herzog, an accomplished student of sublime futility, has made Onoda the subject of his wondrous first novel, “The Twilight World.” The story in his telling seems not so much fictionalized as lightly mythologized. (Herzog, who has admitted to bending the facts even in his documentaries, notes curtly at the book’s outset, “Most details are factually correct; some are not.”)’

(…)

‘Few writers are better equipped to capture a place so overwhelmingly opaque that it lapses into absurdity, and a life that became an exercise in purposed purposelessness. In Herzog’s hands, Lubang exists outside of time, and Onoda’s war has the eerie gravity of a thought experiment come to life.’

(…)

‘He finds meaning everywhere, hearing signals that soon fade into the endless noise. A leaflet proclaiming the end of the war must be a forgery, because it contains minor typos. An errant page from a porno mag, found on the ground, is clearly bait from the enemy. Onoda’s devout belief in his mission becomes a form of schizophrenia, warping everything in its path. Confronted with a newspaper left behind by a search party, he decides that it’s too replete with ads to be real: “They’ve censored the actual news, and replaced it with advertising.”’

(…)

‘Having missed the detonation of the atom bomb, the moon landing, and the rise of mass consumerism, he returned to Japan a postwar Rip Van Winkle, disdainful of its soulless modernity. The nation afforded him a hero’s welcome, enshrining the “Onoda spirit” as an exemplar of lost Japanese duty and discipline. His homecoming “seemed to stir the deepest and most melancholic feelings,” the Times noted. Though “The Twilight World” is full of melancholy, it politely discards such rhetoric. The word “honor” appears only in dialogue—for Herzog, it belongs between quotation marks. If there’s glory in Onoda’s saga, it derives not from patriotism but from his unswerving ability to ignore his own insignificance. Herzog puts an ultrafine point on it: “Onoda’s war is of no meaning for the cosmos, for history, for the course of the war.”’

(…)

‘Herzog, who has made a career studying the emptiness of meaning-making, celebrates Onoda’s noble crusade even as he dismisses its abject triviality; it takes a kindred spirit to admire someone who held himself hostage to a lost cause. Fittingly, Herzog devotes almost none of the novel to Onoda’s life after his long war.’

Read the article here.

I’m going to read the novel in its original language (German), in honor of Werner Herzog of course, but also because there is nothing more delightful than the story of man who ignores his own insignificance.

The search for meaning is the most fragile part of the human condition, fragile and lethal.