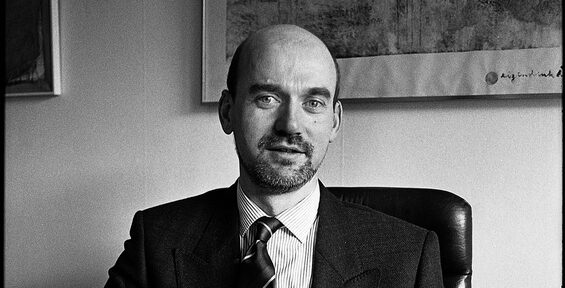

On culture wars and neoliberalism – Merijn Oudenampsen in The New Left Review:

“Twenty years ago, the lifeless body of right-wing politician Pim Fortuyn was found lying on the tarmac outside a radio studio in the Netherlands. He had been fatally shot by an animal rights activist while on the campaign trail for the 2002 elections. Nine days after his death, his eponymous party, List Pim Fortuyn (LPF), won 26 seats and the second largest share of the vote – a historic breakthrough known as ‘the Fortuyn Revolt’. Over the following years, the LPF succumbed to internal strife, but new right-wing populist leaders such as Geert Wilders and Thierry Baudet would follow in Fortuyn’s footsteps.

This year, on the anniversary of Fortuyn’s death in May, Dutch newspapers were filled with retrospectives, looking back on how the populist revolt had changed Dutch politics. A mini-series on his rise to prominence aired on public television, while publishers printed special editions of his bestselling books. Commentators from across the ideological spectrum remarked on his enduring legacy. ‘Fortuyn’s message is in many respects more urgent than before’, proclaimed the centre-left daily de Volkskrant. Yet many of them seemed curiously unaware of what that message was.”

(…)

“Yet ‘Professor Pim’, as his supporters affectionately called him, was never mealy-mouthed about what he stood for. When asked whether he was a ‘populist’ in the radio interview just before his assassination, Fortuyn replied that he didn’t like to ‘suck up to people’. At the beginning of his election campaign, he claimed that ‘not only our politics, but also many of our citizens are useless. They look too much at what the government can and must do, and far too little at what they themselves can do’. Far from rallying against the neoliberal elite, Fortuyn believed that Dutch elites were not nearly neoliberal enough. His hard-right politics were born out of the neoliberal tide that swept the country in the 1980s and 1990s; yet, in the Dutch collective memory, his strident opposition to immigration and Islam would eventually become so all-defining that it would eclipse his economic agenda.

During Fortuyn’s campaign, though, that economic agenda was front and centre. In his bestselling election manifesto, The Disasters of Eight Years Purple (2002), Fortuyn asserted that the Dutch welfare system ‘had given birth to a monster’. The unemployed were ‘a dead weight in society’ with ‘a big mouth’ which the state could not be expected to feed. Unemployment was a dispositional and psychological problem, which could only be solved by slashing welfare, abolishing rent subsidies and cutting disability benefits. Fortuyn proposed doing away with open-ended contracts and introducing a more flexible labour market inspired by the American model, turning the Dutch worker into an ‘entrepreneur of the self’ and making the Netherlands more competitive on the world market.”

(…)

“In this Fortuyn was far from exceptional. During the same period, political scientists such as Herbert Kitschelt and Hans-Georg Betz observed that a series of right-wing populist parties with broadly similar positions had emerged across Europe: Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, Jörg Haider’s FPÖ, the Swiss People’s Party, the Norwegian Progress Party and the Danish Fremskrittspartiet. Many of them started out as ‘neoliberal-populist’ parties before shifting focus and developing into anti-immigration policies. In The Radical Right in Western Europe (1997), Kitschelt described the combination of free-market and anti-immigration policies as a ‘winning formula’ which had become increasingly capable of mobilizing large electoral constituencies. Right-wing populism, he argued, first emerged as an offshoot of neoliberalism. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Fortuyn’s work.

Fortuyn began his storied career as a leftist sociology professor at the University of Groningen. He wrote his PhD on postwar socio-economic policy and developed a close relationship with the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA). But at the end of the 1980s he was swept up in the enthusiasm for neoliberal reform. The government had begun privatizing public assets and liberalizing the economy with the help of a small but growing army of private consultants. Fortuyn wanted to get in on the action. His university seconded him to Rotterdam, where he led a committee that authored a report on the market-led renewal of the troubled port city, which had been hit by mass unemployment.

Fortuyn spent this period at the Rotterdam Hilton, with his bill picked up by city hall. In his autobiography, he recalled consorting with his fellow committee members from the private sector, who taught him how to ‘drink the better wines and appreciate the pleasures of salmon and caviar’.”

(…)

“Tired of austerity and concerned about eroding support, the Christian Democrats tacked left in 1989 and formed a government with the social democrats. Many on the right feared that the momentum for market reform was dissipating. In a much-discussed campaign speech, the Labour Party leader Wim Kok proclaimed that after ten years of neoliberal reform, ‘the pendulum had swung too far’. He criticized the ‘authoritarian governing style’ of the previous decade and promised a restoration of corporatist, consensus politics, with trade unions brought back to the table.

Lubbers was denounced by the right for his betrayal. ‘If only we had a Margaret Thatcher in Dutch politics’, lamented the economist Eduard Bomhoff. Thatcher had fought and defeated the trade unions, while Lubbers mistook consensus for a policy goal. ‘Thatcher’s lessons had been ignored in the Netherlands,’ the journalist Marc Chavannes explained, ‘because we conveniently imagine that she is a mal-coiffed lady in a country full of strange figures who seem to have walked out of a television series.’ ‘How do we get rid of late-corporatist structures’, he went on to ask, ‘which are expressions of a fattened harmony model that threatens the prosperity and well-being of the Dutch people?’

Fortuyn joined the chorus of disappointed free marketeers. In the first half of the 1990s, he published a series of bestselling pamphlets in which he proposed a frontal assault on Dutch consensus politics. Fortuyn complained that Lubbers had squandered a golden opportunity: although he had defied the public sector unions, he had failed to deal them a fatal blow.”

(…)

“This economic agenda was interwoven with a nostalgic longing for what Fortuyn called ‘the human scale’: smaller schools, regional hospitals, workplaces close to home. As he saw it, this scaling down would go hand-in-hand with modernization. Local hospitals would be overseen by specialists from a central location through the use of digital technology. Working close to home was possible thanks to newly established neighbourhood internet pavilions. Fortuyn’s utopian horizon was a curious amalgam of fifties nostalgia and Zoom prophecies. But this striving for ‘the human scale’ was also a thinly veiled plea for more inequality. Fortuyn complained in The Disasters of Eight Years Purple that, under the present system, he received the same care as his cleaning lady while paying much more taxes. This was equivalent to ‘the insurance company that replaces your crashed and expensively insured Jaguar with a Fiat Uno and says: here you are’. On one occasion, when Fortuyn was admitted to hospital, he used this reasoning to demand his own private room, only to be laughed at by the hospital director.”

(…)

“The unrest that unfettered capitalism produced in the socio-economic sphere would be addressed in the cultural sphere. Thomas Frank described a similar process in the United States as ‘The Great Backlash’: politicians mobilized the electorate with ‘controversial cultural themes’ which were intertwined with ‘right-wing economic policies’. For Frank, the resultant culture wars had ‘made possible the international consensus on the free market, with all its privatization, deregulation, and anti-union policies’. Fortuyn’s legacy is to have introduced backlash politics to the Netherlands.”

Read the article here.

Merijn Oudenampsen wrote together with Bram Mellink a thoroughly researched book on the history of neoliberalism in the Netherlands. This article consists, as far as I could lee, largely of excerpts from the book.

Precisely because the article is rather confined the main reason for most if not all of the culture wars cannot be missed: mobilization of the electorate in order to create consensus on economic matters. (I’m saying this as an anti-revolutionary.)

The Dutch journalist Marc Chavannes has a telling role as an extra. In the eighties he wanted to have more Thatcher in Dutch politics, nowadays he is writing for a platform that is not exactly trying to start a revolution, but is largely center-left. Society does exist, also for him.

And the culture wars are bread and games for the people.