On defenestration – Michael Hofmann in LRB:

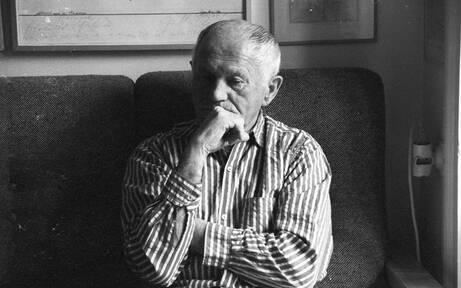

“Things have not gone quiet around the Czech novelist Bohumil Hrabal, even though he has been dead since February 1997, when he defenestrated himself from the fifth floor of a Prague hospital, à la mode tchèque. There were some no doubt well-meaning reports that he had fallen while trying to feed the pigeons, but these should be discounted. Not that he didn’t like pigeons, just as he adored cats and dogs and cows and horses, but his friend, agent and German translator, Susanna Roth, is certain that he meant to end his own life, and dismisses attempts to repurpose his death (often by the same people who had stifled his surly life and enchanting work). ‘Bohumil Hrabal did not die tragically,’ she writes in her 2001 memoir of him. ‘The tragedy here is that his work was over so many years censored in his homeland, and then ignored by critics and public alike, only for his biography to be censored ... Maybe he didn’t deserve such an old age. He certainly didn’t deserve such a death.’”

(…)

“Hrabal’s books – there are more than a dozen now translated into English and probably more to come – are full of this sort of real pain and real disturbance. He started out as a poet, abandoning conventionality for a kind of inspired spatchcock carelessness. He wrote automatically, reflexively, industrially. He pursued the ‘paranoiac-critical method’. He sought out, even arranged, adverse situations for himself: he drank, because he liked to write off his hangovers; he liked looking in mirrors, because it took him so long to get over the awfulness of what he saw there; he liked, and lived by, Joan Miró’s dictum: ‘Il faut être de plus en plus sauvage.’ A life measured out in radial thematic splotches of guilt and joy and shame; in repeated strings of adopted stray cats (which bred and bred and which Hrabal put violently to death: All My Cats is not for the soft of heart); in letters to ‘Dubenka’ and memories of his artist friend Vladimír Boudník, the subject of The Gentle Barbarian; in Prague tales and tales from the forest of Kersko outside Prague; in a shambling youth in provincial Nymburk and a shambling adulthood in industrial Libeň, in the old tumbledown smithy on the so-called Embankment of Eternity, measured out in ‘in-house weddings’ and slaughtering days. As the section ‘Journal Written at Night’ in The Gentle Barbarian has it, repeatedly, ‘back then ... back then ... back then’.”

(…)

“Everything recurs. Nothing gets lost in the desert, Paul Bowles writes. ‘Wichtiges kommt wieder,’ is the way German puts it: important things return. But perhaps one doesn’t know that. Hence Hrabal’s gushing sentences, his spiral or circular forms, his pages written for ‘the luxury of diagonal reading’: the writing compacted, ellipses squeezed out of it like air bubbles, as in Daudet or Céline, a fear of full stops, a contempt for the onward march of paragraphs. (In her 2014 book on Hrabal, Monika Zgustová tells us that each year on 1 May, the holy day of Communism, he made a point of publicly emptying his latrine, a personal ritual whose loud stink interfered with the parp of official power. So much for marching, displays, parades.) Each sentence, chapter, book, is a sack being held open – not for the stray cat, though that as well, but for the familiar, the slogan, the reiterated, the distinctive, the mantric. The books form gabby, unshowy, uncoercive trilogies: there is one about Hrabal’s youth in the provinces (Cutting It Short, The Little Town Where Time Stood Still and Harlequin’s Millions); another about his married life, put into the mouth of Pipsi (In-House Weddings, Vita Nuova and Gaps). They refer to one another, all drawing insistently and mythically on Hrabal’s life. They are forever in and out of each other’s houses, popping in to borrow a cup of sugar, rehashing old conversations, old memories. ‘As I was saying a moment ago.’ And then maybe saying something different. Or not – it barely matters.

I became so severely addicted to Hrabal that I started buying up old copies of the German editions, published by Suhrkamp in block colours with a single, contrasting stripe. Orange, lemon, lime, black. I own about a foot and a half of these now, and am somehow still being caught out by further, half-familiar titles. Do I own a copy of Ich dachte an die goldenen Zeiten (‘I Thought about the Golden Times’), and if not, how not? Does it exist? Hrabal in English presents a strangely uncharted, almost unnavigable oeuvre, the plethora of publishers (the punt, the suspension, the cessation, the resumption), the oddly alienated titles, the absence of chronology – except that one still can’t really go wrong in it. Broadly, Hrabal worked in the 1940s (as a train dispatcher, in a steel mill, in the paper plant); wrote in the 1950s; published in the 1960s; was banned in the 1970s; became popular and famous and unhappy and compromised in the 1980s. In Czechoslovakia, his books were variously burned or seized or given prizes; some were published in samizdat editions, some appeared in censored versions, others were smuggled out to émigré publishers abroad (notably, to Josef Škvorecký’s 68 Publishers in Toronto). Now they have come full-circle, and many of them are published by English-language publishers in Prague. It’s hard to think of another writer so unconventionally formed, so rebelliously syncopated, so shamefacedly detached from the conventions of writing and publishing.”

(…)

“The Hungarian novelist Péter Esterházy wrote that ‘in Hrabal’s books, the world doesn’t become any more beautiful or true, it just becomes real.’”

Read the love declaration here.

For some reasons, mainly circumstances, I have never indulged myself in Hrabal.

Hofmann is funnier when he is butchering a book, but the Esterházy quote is what I believe that a novel should do. (A poem is allowed to do other things as well.)

And Miró of course. Yes, and yes, and yes. But how?