On appetite – Sam Leith in TLS:

‘The contours of Dahl’s strange and disaster-strewn life – in which his children’s writing career sometimes seems almost to have been an afterthought or an accident; he was well into his fifth decade before he published James and the Giant Peach (1961) – are zippily mapped. There’s the death when Dahl was an infant of his older sister Astri, then of his father, Harald – a situation that left him the adored only boy in a family of women. His relationship with his Norwegian-born mother, Sofie Magdalene, was perhaps the most important in his psychological make-up (“Apple”, he was nicknamed) and they corresponded until she died. Their visits to his grandparents in rural Norway nourished his interior mythology and supplied him with the robust Norwegian grandmother in The Witches (1983).’

(…)

‘In Boy he reported that the future Archbishop of Canterbury Geoffrey Fisher (who had been headmaster of Repton) had given a savage and unwarranted thrashing to Dahl’s best friend. Fisher had left the school by the time of the incident – and the boy in question had been sexually interfering with younger boys. What’s telling is not (quite) that Dahl got it wrong, but that when the mistake was pointed out, he refused to revise the text.’

(…)

‘Dahl’s sexual career, in his single days, was quite something. At eighteen, en route to an outdoorsy boys’ camp in Newfoundland, he had an on-ship romance with an actress two years his senior. His early twenties saw “a sequence of more or less furtive romantic and sexual entanglements, including with older married women” in that hotbed of extramarital shenanigans, Bexley. He really hit his stride during his years in Washington as an assistant air attaché to the embassy. “I think he slept with everybody on the East and West Coasts that had more than fifty thousand dollars a year”, reported one contemporary.’

(…)

‘That wasn’t the only respect in which his time in the US shaped and typified him. During his sojourn in the States he had his first literary success with a whimsical 7,000-word story (he called it “a sort of fairy-tale”) about supernatural “gremlins” that sabotaged RAF planes. The young Dahl was courted by Walt Disney to turn it into a movie – but he behaved towards the mogul with the same arrogance and implacability that would characterize his dealings with agents, editors and tax authorities through his career. The Gremlins never got made. No matter. Dahl made himself comfortable among the monied and well connected. He published stories in the New Yorker, cuckolded eminent citizens, dined with Roosevelt – and, as if living in a fantasy of his own life, even did some espionage work on the side. When he was shown in confidence a draft document by the vice president Henry Wallace, which suggested that the US should encourage Britain’s Pacific colonies to declare independence after the war, he sneaked it off, copied it and caused it to reach the eyes (at least in his account) of Churchill.’

(…)

‘Few writers, except perhaps Hemingway (whom Dahl admired, incidentally, until he saw him administering hair tonic), have been such men of action. Even his early fad for photography (shared, suggestively, with Lewis Carroll) and later manias for gardening and picture-framing showed a cast of mind that was above all practical.’

(…)

‘Whether you be a cane-wielding headteacher or a graceless, gum-chewing little girl, if you’re a baddie you are going to get what’s coming to you; and the audience will do nothing but rejoice in the cruelty of your punishment. As he put it himself towards the end of his life: “I’m afraid I like strong contrasts. I like villains to be terrible and good people to be very good”. That made for a strong natural connection with young audiences, who, rather than be preached to by “improving” literature or have their view of the world complicated by “literary” literature, enjoyed having their world-view affirmed with – I think it’s the right phrase – extreme prejudice. Children are vengeful little brutes.’

(…)

‘Dennison makes the traditional argument for separating the art from the artist. He quotes the critic Kathryn Hughes arraigning Dahl for “grandiosity, dishonesty and spite”, and says that they “play no part in the writing that constitutes his continuing claim to our attention”. There, I wonder. As Matthew Dennison amply shows, Dahl’s work was intensely personal. Like many children’s writers, he wrote for and from his child self. And the spite? Well, when it comes to Dahl that’s the good stuff.’

Read the article here.

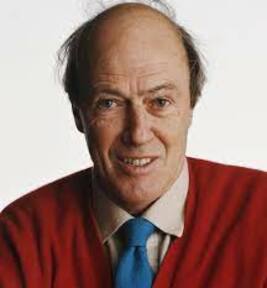

I was never a great admirer of Roald Dahl the author of children’s books. Yes of course, there was the chocolate factory, but I never admired with the same passion that I felt for other books.

But his tales for adults made later a huge impression on me. They tingled me with excitement for their nastiness and eroticism – and there the simple morality seems to be taken over by something much more complicated, a universe where con men and some others who happen to have just enough bravado get away with everything.

Action is better than words, as he himself stated.

And to bed only mortals who make more than fifty thousand dollar a year, adjusted for inflation approximately seven hundred thousand dollars a year nowadays, is a wise principle.