On Romanticism – Ben Hutchinson in TLS:

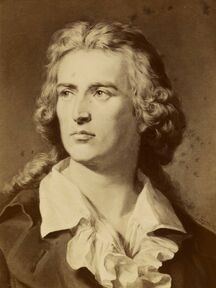

‘The terms of this era had been set, politically speaking, by the French Revolution. The terror that it unleashed pushed progressive German thinkers into conceiving of Europe as a cultural rather than a military space: Schiller’s journal Die Horen (1795-7), for instance – a key forum for the development of the Jena Set – included his ownLetters on the Aesthetic Education of Man (1795), which argued that art could help to bring about a kinder, more ethical revolution. Goethe and Schiller’s relationship exemplified that intention, but it isn’t what interests Wulf the most. Rather, the two older poets are the foil for a younger generation of thinkers and critics born in the 1760s and 1770s: Fichte, Novalis, Schelling, Tieck, August Wilhelm and Caroline Schlegel, Friedrich and Dorothea Schlegel, Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt. In Germany as in England, early Romanticism was nothing if not a group production.’

(…)

‘Fichte’s influence grew. Few of his students fully understood what he wrote, but for the young poet Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg) he was a “second Copernicus”, revolutionizing our view of internal consciousness. The dreamiest of thinkers, Novalis developed a death wish following the passing of his fifteen-year-old fiancée, Sophie von Kühn. By day a mild-mannered inspector of mines, by night a herald of Sichselbstfindung, or self-discovery, Novalis gave voice to subterranean experiences both literal and metaphorical in Hymns to the Night (1800). The most representative poems of early Romanticism, they exemplify the turn away from Enlightenment metaphors to an earthier, chthonic idiom.’

(…)

‘Collaboration, inevitably, also meant confrontation. It was in the nature of such an intense period to be short-lived, like the journals that came to define it, and a series of fights, feuds and scandals duly ensued. The first and perhaps most consequential of these was between Schiller and the Schlegels. In part it was the usual story of younger intellectuals trying to replace their elders. But it was also temperamental: Friedrich Schlegel could not resist attacking others, even the influential (and notoriously thin-skinned) Schiller. By the middle of 1797 the younger Schlegel had written a series of negative reviews of Die Horen, criticizing its reliance on translations of foreign literature – much of which had been done by his brother August Wilhelm. Schiller promptly dropped them both.’

(…)

‘That they were successful in doing so is clear not just from their influence on the English Romantics – the standard example being the Germanophile Coleridge – but from their reception across Europe and beyond. “Germanomania”, as the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz put it, swept the western world, and “Europe” constituted a key category in the Romantic imagination, as attested by another short-lived journal, Friedrich Schlegel’s Europa (1803-05). The pathos of the preface to the first issue leaves the reader in no doubt as to Schlegel’s lofty aims, which were “to spread the light of beauty and truth as widely as possible”. That light carried on spreading well after the end of the movement: Wulf’s epilogue gallops through its more obvious heirs, from the American transcendentalists to the European modernists. A somewhat cursory comparison between Lucinde and Finnegans Wake fails to make the case for direct influence – Joyce had read about the Jena Set in Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria and “might also have studied other translations and critical essays” – but there are certainly parallels between Schlegelian Romanticism and Joycean modernism in their treatments of subjectivity, fragmentation and overambitiousness.

The remaining question is why Jena Romanticism took hold where and when it did. Reaction against the Enlightenment is one answer, but why in Germany? De Staël’s explanation was that German thinkers escaped to an “Ideal” world because their reality was so underdeveloped – because Germany, in short, did not yet exist, divided as it was between the hundreds of competing principalities that formed the Holy Roman Empire. Facilitated by the freedom from censorship that such a fissiparous political landscape permitted, Romanticism emerged as a manifestation of what Helmuth Plessner would later call the verspätete Nation, the delayed nation that would accrete, then expand, so explosively in the twentieth century. In the meantime culture developed in place of country.

Other, more local factors played a role, not least the thriving centre of culture that was Weimar, which administered Jena on behalf of the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar. One of the most significant absences in Wulf’s narrative is any sustained engagement with Weimar classicism. Goethe and Schiller were a half-generation older than the Jena radicals, and so played correspondingly semi-detached roles in their development, as contested parent and fiery elder brother respectively. Their own relationship, from 1794 to Schiller’s death in 1805, is often taken to be the core of Weimar classicism, but Wulf has little to say about it, and the importance of Herder (for example) to the older generation is barely mentioned. As early as 1795 Schiller told Fichte that “posterity will turn us from contemporaries into neighbours, although we actually had little in common”.’

(…)

‘Wulf’s book reads as much like a novel as an intellectual biography. She is an expert at compressing her sources – letters, diaries, journals – into the kind of prose we recognize from nineteenth- century realism, complete with free indirect discourse (“Friedrich Schlegel was having fun”; “Duke Carl August was furious with Fichte”). This is fair enough – the sources are meticulously documented – but it raises the question of whether Wulf retains sufficient critical distance. Perhaps, in the end, her subjectivity is only too apt. Novalis suggested to Caroline Schlegel that they should turn their lives into a novel, and Andrea Wulf has taken up the challenge – not in the sense that Magnificent Rebels is made up, but in the sense that she imagines the lives of the Jena Set from the inside out. It is a considerable achievement.’

Read the article here.

German Romanticism consisted first and foremost of magazines, but its influence, as this essay also points out, was immense.

What Novalis meant exactly when he wrote that life should be turned into a novel is probably more obscure than Hutchinson suggests.

When Coetzee in ‘Slow Man’ has Elizabeth Costello say to Paul Rayment ‘live like a hero. That is what the classics teach us. Be a main character. Otherwise what is life for?’ Costello and Coetzee are echoing Novalis.