On luck – Andrew Preston in TLS:

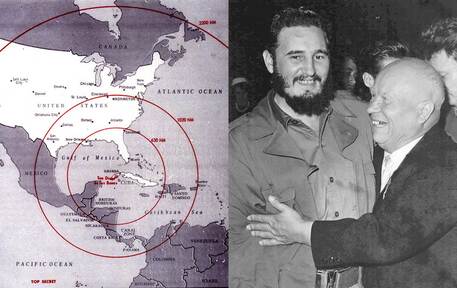

‘The “eyeball to eyeball” stand-off over Cuba was the worst of the Cold War’s many terrifying crises, the closest the superpowers came to all-out war. All this has been the subject of countless books, articles and conferences; Abyss joins a dozen other titles on the topic just on my own shelves, in addition to the many Cold War histories alongside them in which the crisis features prominently. Do we really need another book on the “Thirteen Days” of October 1962? It depends on the book. Hastings is generous to a fault in acknowledging the work others have done before him, yet he is the right person to tell this story: he has few peers as an expert in military and diplomatic history, and few historians have his ability to write a narrative that is at once deeply researched, incisively intelligent and compulsively readable. Abyss is as tight and smart as any account, and will earn pride of place even on a shelf already packed with books about the crisis.’

(…)

‘Perhaps the book’s most interesting contribution is its reassessment of the key figures, for this really was a historical moment driven by personality, which turned on individual decisions. Of the three key players, only John F. Kennedy comes out with his reputation intact, indeed burnished. Hastings doesn’t hesitate to point out his mistakes, but throughout the American president seems to be the only sane person in the room. By contrast, Nikita Khrushchev is one of the book’s main villains, albeit a very human one: ambitious and impulsive, but also vulnerable and bewilderingly inconsistent. The megalomaniacal Castro, almost suicidally committed to resisting Yankee aggression at any cost, even nuclear war, is subject to stern criticism. Of the supporting cast Hastings praises Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk for encouraging Kennedy’s diplomatic manoeuvres. He saves his harshest words for the Strangeloveian US military, which pushed relentlessly for authorization to bomb and invade Cuba despite – or, for some of the brass, precisely because of – the chance that it would lead to World War Three. The civilian members of the White House’s fabled ExComm who advocated for military intervention also come in for stinging criticism. Hastings is shrewd to zero in at times on the hawkish National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, one of Kennedy’s less famous but most important aides, who was “so smooth and smart that you could have played pool on him”, but whose surface polish concealed some poor judgement.’

(…)

‘Some US officials, including Bundy, did in fact push for war in Cuba, then in Vietnam. Yet that line wasn’t always so straight: in 1964-5 the Joint Chiefs were actually reluctant to wage war in Southeast Asia, while McNamara and Rusk, the civilian voices of reason during the missile crisis, applied the crisis-management techniques that were so successful in Cuba to the conflict in Vietnam, this time with disastrous results.

What, then, were the lessons of the Cuban Missile Crisis? As Vladimir Putin rattles his nuclear sabre over Ukraine, what can Joe Biden learn from his hero Jack Kennedy? Not much, it seems. “In 1962, the world got lucky”, Hastings concludes. Let’s hope we get lucky again.’

Read the review here.

Refreshing to see a famous quip by Voltaire rephrased, the only lesson history is teaching us is that nothing can be learned from history.

It always helps to get lucky, it always helps to have a few winnings strikes, before you get unlucky and you die.