On big and small – Merve Emre in NYRB:

‘The pleasures of making it big and making it small and not noticing or caring who gets hurt in the process—this is the gimmick on which nearly all Dahl’s children’s books turn, the gimmick that reveals the hollowness at their center. It begins with James and the Giant Peach (1961), his first serious attempt at children’s fiction, in which a peach crushes James’s spinster aunts and rolls off with him and a host of giant insects inside. It is no longer possible for me to read “Bigger and bigger grew the peach” without hearing its echo, thirteen years later, in “Bitch.” Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964) squeezed, shrank, and stretched its spoiled children, their punishments doled out by the Oompa-Loompas—described in the first British edition as a race of “amiable black pygmies” imported to England from “the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle” by Willy Wonka, who invites them to work as chocolate makers in exchange for an endless supply of cacao beans.’

(…)

‘Reading Dahl’s books to my children in swift succession over the past few months has reminded me of Samuel Johnson’s complaint about the comedy of Gulliver’s Travels: “When once you have thought of big men and little men, it is very easy to do all the rest.” Easy it may be, but the results are very wide-ranging indeed. Dahl’s fictions of scale are the stupidest and crudest I have encountered. They have none of the unearthly enchantments of Grimms’ Fairy Tales or Diana Wynne Jones’s Howl’s Moving Castle; none of the madcap philosophical sophistication of Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth or Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, whose title character is forever stretching out or shutting up like a telescope; none of the intricate, if somewhat tiresome, world building of L. Frank Baum’s Oz books or Enid Blyton’s The Faraway Tree; none of the genuine ethical and political complexity of the three greatest children’s authors, Edith Nesbit, C.S. Lewis, and Edward Eager. With few exceptions, size, in Dahl’s imagination, is nothing more than a proxy for force. Largeness indicates the power to manipulate and coerce; smallness indicates vulnerability to punishment and annihilation that must be overcome through trickery. Even his happiest endings left my children listless and a little depressed, as if they intuited that what had seemed at first to be the pursuit of justice in an unjust world was nothing more intriguing than a game of bloody knuckles, a theater of schoolboy cruelty.’

(…)

‘Pull back the curtain on this world and you will find its creator, a man who, by many accounts, lived much of his life feeling like a small, fretful, persecuted boy, even though he was, by midcentury, a fighter pilot turned spy, a spy turned playboy, and from the 1960s on a very wealthy, very popular writer. The enduring irony of Dahl’s career is that children’s literature was the only corner of the literary marketplace where he could make it big and stay big. He had tried his hand at adult fiction, writing stories about his wartime exploits for The Saturday Evening Post in the 1940s, gothic tales about unhappy marriages for The New Yorker in the 1950s, screenplays for the Hollywood studios in the 1960s. He had dreamed of being Ernest Hemingway. He ended up a third-rate Shirley Jackson, writing lurid fantasies about rape and wife swapping for Playboy and the screenplay for You Only Live Twice, the Bond adaptation that ruined Bond adaptations. Only then could he commit fully to children’s literature, where he thrived financially. His preoccupation with size bears the ambivalent imprint of his successes and failures—the anxieties of a man who appeared, from one angle, too big to fail, and, from another, too small to take seriously.’

(…)

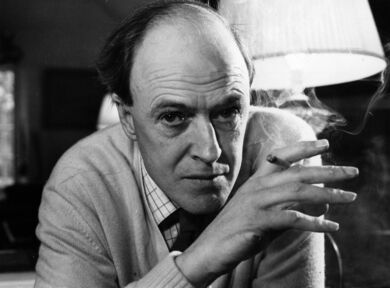

‘Part of the challenge is that Dahl told much of his story himself, beginning with his memoir Boy (1984), which narrates the first eighteen years of his life with little concern for getting the facts straight. Yet one would rather read his stories, however fanciful, than incurious or pedantic paraphrases of them. The indignities of his life are the indignities of the British bourgeoisie, although with a greater share of domestic tragedy than most. He was born in 1916 to a wealthy Norwegian shipbroker and his second wife, the youngest son in a family of seven children. When he was three, his older sister died of appendicitis, and his father died weeks later, some said of a broken heart. In accordance with his father’s dying wish, his mother sent him to the finest grammar schools. There he was regularly beaten by the teachers and older boys—hazed, caned, mocked for his tears. Dahl wrote that “a boy of my own age called Highton was so violently incensed” after one of Dahl’s beatings “that he said to me before lunch that day, ‘You don’t have a father. I do. I am going to write to my father and tell him what has happened and he’ll do something about it.’” It is strange that none of his biographers make much of the loss of his father, beyond pointing out the obvious, that his children’s books often feature orphans or children with cruel, neglectful parents. Biography is not psychoanalysis, of course, but when the symptoms float so close to the surface, it makes little sense not to cast one’s net. For he prided himself on growing bigger than his tormentors, so big that he didn’t need a father around to “do something about it.” He shot up to an astonishing six foot six, with pale blue-gray eyes, a high forehead, and a handsome jaw; a solidly middle-class English boy at once fascinated and repulsed by the English institutions his dead father had extolled, with a noticeable dependency on the admiration of his mother and sisters.’ (…)

‘He joined the British embassy in Washington, D.C., in 1942 as an assistant air attaché, one of the many grammar school boys eager to try his hand at espionage, trading sex and secrets with the rich and famous, while selling his war stories to The Saturday Evening Post. In any given month, the first weekend might find him at Hyde Park or the White House alongside the First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt; the second at the poker table, losing the thousand dollars he claimed to have been paid for a story to Senator Harry Truman; and the third and fourth in the bed of Clare Boothe Luce, an asset he boasted about cultivating. He lived with the advertising mogul David Ogilvy, drank with Isaiah Berlin and Ian Fleming, “slept with everybody on the East and West Coasts that had more than fifty thousand dollars a year,” marveled Antoinette Marsh, daughter of the newspaper magnate and oil tycoon Charles Marsh.’

(…)

‘It is difficult not to read the books that follow as testifying to the unhappiness of the union. The short stories from the late 1940s to 1970s collected in Someone Like You, Kiss Kiss, and Switch Bitch are a mix of horror, satire, and smut—memorable, if they are memorable at all, for their possibly campy, possibly misogynistic twists. A pleasant elderly landlady turns out to have a nasty habit of poisoning her young male lodgers and turning them into taxidermied figures. Two neighbors sneak into each other’s houses to have sex with each other’s wives under the cover of dark; the next morning, their wives reveal that last night was the first time they ever felt sexually satisfied. For a short period of time, Dahl had a contract with The New Yorker, but it was allowed to lapse in 1960, when Katharine White, the magazine’s fiction editor, simply stopped replying to his submissions.’

(…)

‘But what use was such happiness when he was aged and ailing and brimming with meanness? His children were in various states of disrepair, addicted to drugs and alcohol and bad behavior. His art, if one could call it that, was increasingly a source of struggle. There is, across all the biographies, a strange sense that, for Dahl, life did not grow bigger and richer, but smaller and shallower—that, by the end of it, he had shrunk into himself, rather like Mr. and Mrs. Twit.’

(…)

‘Matilda’s smallness thus differs from ordinary human vulnerability. It measures the cultural fragility of reading literature in a world that refuses to protect or nourish it. This is the hidden meaning of the book’s opening chapter, which still stands, in my grown-up mind, as the most moving first chapter in children’s literature. After some swipes at children whose parents overestimate their talents—more pleasurable now that I regularly interact with other parents—Dahl introduces us to the book’s central conflict, between the desire to read and the belittlement of this desire by forces that no single reader can subdue on her own. Matilda asks her father for a book:

“Daddy,” she said, “do you think you could buy me a book?”

“A book?” he said. “What d’you want a flaming book for?”

“To read, Daddy.”

“What’s wrong with the telly, for heaven’s sake? We’ve got a lovely telly with a twelve-inch screen and now you come asking for a book! You’re getting spoiled, my girl!”

What is a child to do? Mike Teavee, from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, would plunk himself down in front of the idiot box. Four-year-old Matilda marches herself straight to the public library. The librarian, Mrs. Phelps, is pictured in Quentin Blake’s illustrations as a colossus bestride the pale, wondering girl.

Mrs. Phelps is a model of benevolence and tact, one of only two good and true adults in the book. She asks and wants nothing from Matilda—only guides her to a reading chair and to a copy of Great Expectations. Blake’s illustration portrays her sitting in a gigantic chair, with the great frame of a book occupying the whole of her tiny lap. The reader half expects her to be leveled and crushed by literature, but this is precisely the illusion from which the illustration gains its pathos.’

(…)

‘The descent from the pastoral magic of literature to its institutional legitimation at the book’s end is a hard pill to swallow—as difficult, for me at least, as it was to learn the story of Matilda’screation. For Dennison, Matilda testifies to the growing success of Dahl’s creative partnerships in old age, above all his marriage to Liccy. On this point, he quotes with approval an obituary written by Dahl’s daughter Tessa: “She fed him with such affection and cared for him with so much devotion that his heart sang; it is she we must give thanks to for Matilda.” Treglown, by contrast, makes it clear that the published version of Matilda owes a great deal more to the interventions of Dahl’s editor, Stephen Roxburgh, than it does to his romantic awakening. The Matilda of Dahl’s first draft was “born wicked” and most likely based on Hilaire Belloc’s poem “Matilda”: “Matilda told such Dreadful Lies,/It made one Gasp and stretch one’s Eyes.” This Matilda tortured her kind parents, declared war on her cross-dressing, mustachioed headmistress, and used her powers not to read but to fix a horse race so that her favorite teacher, Miss Hayes, a compulsive gambler, could pay off her debts.

Roxburgh gave Dahl everything that makes Matilda appealing: Matilda’s unassuming intelligence, the horrendous Wormwoods, the dovelike Miss Honey. He shaped Dahl’s lazy nonsense into a story, with a beginning, middle, and end.’

(…)

‘He was doomed to live with himself, nursing his childhood hurt, his raw prejudices, his eternally wounded pride. For that, he deserves as much of our sympathy as any person, big or small, who has stumbled over his own two feet while walking the earth. In this sense, and in this sense alone, his extraordinary life was a perfectly ordinary, perfectly grown-up tragedy.’

Read the article here.

This is quite an exquisite hatchet job. Poor Roald Dahl must die again, Mr. Matthew Dennison, his latest biographer, is just collateral damage. (‘It is worth noting that Dennison is mostly a biographer of grand English ladies—Princess Beatrice, Queens Victoria and Elizabeth II, Vita Sackville-West—and one cannot help but wonder if his latest is a chummy attempt to redeem a beloved British cultural export now that the royals have proved themselves to be beyond redemption.’) As one can see Merve Emre is very good at intelligent nastiness, and fair enough both Mr. Dennison and Mr. Dahl might deserve this nastiness.

I was never the biggest fan of Roald Dahl but I did enjoy ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ and some of his adult stories as well, for example ‘Lamb to the Slaughter.’ That Dahl appeared to be a rather unpleasant person has very little to do with the quality of his books. Talent is not an excuse for boorish behavior, I phrase it mildly, but boorish behavior is not a valid argument to pass a damning judgment on books, symphonies, movies or paintings. The desire to let only the impeccable few into the pantheon of true art is above all an old-fashioned Christian reflex.

Now back to Dahl, the only book that is worth reading (Matilda) according to Emre was not written by him, it was ‘saved’ by his editor. ‘Treglown, by contrast, makes it clear that the published version of Matilda owes a great deal more to the interventions of Dahl’s editor, Stephen Roxburgh, than it does to his romantic awakening.’

A main argument against his children’s books comes from the children of the reviewer: ‘Even his happiest endings left my children listless and a little depressed, as if they intuited that what had seemed at first to be the pursuit of justice in an unjust world was nothing more intriguing than a game of bloody knuckles, a theater of schoolboy cruelty.’

The argument from authority. Sort of.

So, an unintended side effect of the harshness, sometimes even crudity of this funny and as I said delightful review (yes, also delightful) is that the reader comes to the conclusion thate he should give Roald Dahl a third or fourth change.

Maybe he should end up in the dust bin literature, maybe. But Merve Emre awoke the Jesus in me. ‘I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance.’

Repentance is for later. Let the sinners enter my bookshelves.