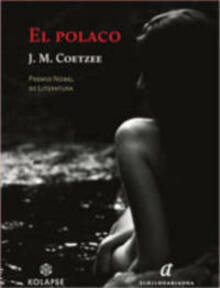

On ‘El Polaco’ or 'The Pole' or 'De Pool' – Colin Marshall in The New Yorker:

‘It may come as a surprise to most of J. M. Coetzee’s readers that he published a new novel in August. “El Polaco,” which is set in Barcelona, is about a romantic entanglement between Witold, a concert pianist of about seventy known for his controversial interpretations of Chopin, and Beatriz, a music-loving Catalan woman in her forties who assists him during his stay in the city. Fired more by mind than body, the two attempt to conduct their affair using the kind of stilted, colorless “global English” to which international communication so often defaults. Apart from an initial carnal encounter, their romance takes place in large part by correspondence: Witold writes Beatriz poems, but, with English verse lying beyond his grasp, he does so in his native Polish. Beatriz engages a translator in order not just to understand but evaluate Witold’s poems, which she gives modest marks.’

(…)

‘“El Polaco” has so far only been published in a Spanish translation. The translator, Mariana Dimópulos, played an unusually active role in the novel’s creation: Coetzee has spoken of incorporating her suggestions about how a woman like Beatriz would think, speak, and act back into the original manuscript.’

(…)

‘The grandson of “Afrikaans-speaking anglophiles,” he grew up using English at home with his mother and father; “both parents would have associated English with high culture and Afrikaans with low,” though other relatives mixed the two freely. (In the autobiographical “Boyhood,” Coetzee writes of suddenly coming into bilingualism: “He still remembers how he burst in on his mother, shouting, ‘Listen! I can speak Afrikaans!’ ”)’

(…)

‘In a 2019 interview at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Coetzee himself said that “as a child, as a young man, as a student, I had absolutely no doubt that access to the English language was liberating me from the narrow world view of the Afrikaner.” But maturity has introduced a distance: “I have a good command of English, spoken and written, but more and more it feels to me like the kind of command that a foreigner might have,” he said, in 2018, at the Hay literary festival in Cartagena. “This may be the reason why the English I write is so easily translatable. I’ve worked closely with translators of my books into languages that I know, and it seems to me that the versions that my translators produce are in no way inferior to the original.”’

(…)

‘In recent years, Coetzee has become particularly involved with Argentinean literary culture. His relations with that country began late in his life, he said in a 2015 talk at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, and “came as a considerable surprise.” From his first trip to Argentina, Coetzee said, he encountered “a reading public that really took books seriously and read books intelligently.” Beginning in the mid-twenty-tens, Coetzee directed a seminar series on literature of the Southern Hemisphere at the Universidad Nacional de San Martín; he has also curated a “personal library” series for the publishing house El Hilo de Ariadna. (His selections include Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” Samuel Beckett’s “Watt,” and Patrick White’s “The Solid Mandala.”) But the major work of his Argentinean period, and clearest literary reflection of his evolving views on language, has been a trilogy of novels: “The Childhood of Jesus,” “The Schooldays of Jesus,” and “The Death of Jesus.”’

(…)

‘Coetzee has told the Spanish-speaking press that the Spanish translation of “El Polaco” reflects his intentions more clearly than the original English text does. That he chose to publish the translation first through El Hilo de Ariadna reflects his distrust of the language through which he has become such a venerated figure. “I do not like the way in which English is taking over the world,” he declared, at the Hay literary festival. “I do not like the way in which it crushes the minor languages that it finds in its path. I don’t like its universalist pretensions, by which I mean its uninterrogated belief that the world is as it seems to be in the mirror of the English language. I don’t like the arrogance that this situation breeds in its native speakers. Therefore, I do what little I can to resist the hegemony of the English language.”’

(…)

‘His growing alienation from that language has bought his writing closer to that of Beckett, in the latter’s French period—or to that of Nabokov, whose “feeling for English words is exact,” as Coetzee writes in the notes of one lecture from his university-professor days, “but deliberately remains that of a connoisseur, an outsider.”’

(…)

‘Out of a desire to better understand the peculiar strengths of Coetzee’s prose—which makes an impact of a kind seldom felt in the writing of native speakers—I’ve spent the past two years retyping the entirety of his autobiographical trilogy, “Boyhood,” “Youth,” and “Summertime.” In South Korea, where I now live, this practice is called pilsa, and its many practitioners use it to improve their writing skills, not only in Korean but also foreign languages, most popularly English. Coetzee would surely grumble at that, but I like to think he’d approve of my own pilsa routine, which also involves retyping the collected works of Borges—in the original, of course.’

Read the article here.

The Argentinean period – it’s always helpful to divide the work of artists and writers into periods. I’m curious to see what the next biographer of Coetzee is going to write about his Argentinean period and I’m going to reread the Jesus-trilogy, because in my recollection the role of Spanish in this trilogy was merely the role of the other, the other language, maybe also as in: the other woman.

(Is it possible to have an affair with a language?)

Nabokov indulged in his role as connoisseur of the English. That’s why he can be unbearable. To Coetzee English is a tool – there is no such thing as indulgence, because how can you indulge in a hammer?

As to the arrogance of the English language. American culture has conquered many parts of the world. The language just followed. If I think of the Netherlands I would say that many inhabitants came to regard the English language the same way as Coetzee did in South-Africa, an escape, the way towards upward social mobility. They might be right of course. Or at least, the misunderstanding can be understood.

Recently, I visited a prison for asylum seekers in a town in Poland not far from the border with Ukraine. A guard and refugee from Iraq spoke a language with each other that might be called global English. Global English is still very much in development and maybe one day it will be a language by itself. Think of Pidgin.

Once there was Latin then there was French, then globalization got democratized and we got global English, still under construction.