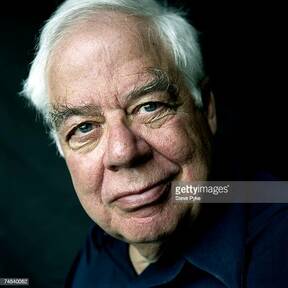

On a vacation - Mark Edmundson in Harper’s:

‘He was also a committed leftist, a child of Trotskyists, and a lifelong champion of the progressivism of his Depression-era upbringing. But none of that changes the fact that Rorty dedicated his life to advancing a view of truth—philosophical pragmatism—that helped lead Donald Trump to the White House.

Though it is generally viewed as America’s great contribution to Western philosophy, pragmatism isn’t a philosophy per se—if by a philosophy one means a particular view of reality that a given philosopher or school of philosophy endorses. It is better understood as an approach to the world. At its heart is a conception of truth put forward by the nineteenth-century polymath Charles Sanders Peirce. Peirce studied chemistry and worked as a government land surveyor, and his philosophical views were deeply indebted to the scientific method. Essentially, Peirce argued that the meaning of any statement lay in its predictive value—that is to say, in its practical consequences. To describe an element as highly flammable, for example, was not to attribute to it some metaphysical quality, but simply to say what would happen if one applied a flame to it.

Many strong minds have revered Peirce—Cornel West has said that his achievement in philosophy is comparable to Melville’s in literature—yet he is perhaps the most obscure consequential thinker America has produced, and his views have survived mostly in the reworked interpretation of his near-contemporary William James.’

(…)

‘At its best, pragmatic practice is forward-looking, optimistic, and labor-intensive. What a pragmatist achieves should never be an end in itself, James insisted, but rather an inspiration for more work. To James (and to Rorty), we are best off when we see our lives as open-ended projects that prioritize process over arrival. But as a philosophical tradition, pragmatism makes no normative claims about what is worth doing and what is not, what is desirable and what is to be abjured. Bloom and West both correctly identify one root of pragmatism in Ralph Waldo Emerson, and in particular those of his passages—there are plenty of them—that affirm power without worrying about what sort of power is in question. In “Circles,” an essay Rorty particularly admired, Emerson talks about how a potent mind can expand until it achieves power not only over itself but over aspects of the world:

The extent to which the generation of circles, wheel without wheel, will go, depends upon the force or truth of the individual soul. For it is the inert effort of each thought, having formed itself into a circular wave of circumstance,—as, for instance, an empire, rules of an art, a local usage, a religious rite,—to heap itself on that ridge, and to solidify and hem in the life.

The inspired mind creates local customs, works of art, religious rituals—and also empires. About the creation of such empires, Emerson is not apologetic. It is an amoral passage that helps give rise to an amoral movement.

But in my view, pragmatism is not the invention of Emerson or Peirce or James. It is rather the crystallization of long-standing tendencies in American culture. Pragmatism begins on the streets and exchanges, and is later articulated in the halls of academe. Its practitioners love talking about the “marketplace of ideas”—a phrase adapted from the pragmatist jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., and not one you’re likely to hear spoken approvingly by a Kantian or a Hegelian. Pragmatism guides the way many, if not most, Americans conduct their daily lives: with an eye to work, success, profit, achievement, innovation, and ongoing expansion.’

(…)

‘In a lecture I watched him deliver around the time Achieving Our Countrywas published, Rorty answered a question about pragmatism by saying, “Perhaps we should simply pretend that Truth has gone on vacation for a while.” Rorty was aware that he was sometimes accused of saying things to “get a gasp.” The audience did gasp—and laughed nervously. What Rorty meant was that we should give up on the quest to find some capital-T Truth about human experience that would be absolute and binding for all time. Instead, we should seek provisional truths that help us better lead our lives. And when these truths fail to put us in an agreeable and productive relation to the world, we should jettison them and search for new ones.

It’s important to distinguish pragmatism from the various forms of postmodern thinking that were so trendy in Rorty’s day. In many ways, his affirmation of pragmatic, small-t truth was a reaction to Jacques Derrida’s brand of deconstruction. I recall Rorty coming into a seminar we were teaching on literary theory with a grin on his face. He’d gotten it, he told me. He’d come up with a compressed way to explain what Derrida was up to. Derrida’s work, he said, could be seen as a polemic against closure. Derrida never wanted to stop interpreting: he would compound one association after the other, unceasingly, relentlessly. If you never stop interpreting, then there is “nothing outside of the text.” Why should artificial boundaries stop us from continuing to interpret? A book only appears to end on its final page: there are other books and other thoughts that it suggests, creating an endless web. So why stop reading and construing?’

(…)

‘It has been said many times that Trump was—in his own bizarre fashion—a postmodernist president. Those who say this generally use the term “postmodern” loosely. They mean that Trump cared nothing for tradition, had no regard for truth, that he lied all the time. But Trump is far better understood as our first pragmatist president. Trump knew—and knows—that Truth has gone on vacation; his acolytes know it, too. They are not nihilists, as they are often labeled, for they clearly do value something. And they are not deconstructionists, for they are prepared to latch onto pragmatic truths that will get them what they want.

Trump’s language is, or seeks to be, performative. He speaks to advance his cause and confound his enemies. To achieve this, he will say virtually anything. His followers—disillusioned people who have been stripped of ideals—are responsive to his reckless pragmatism and employ it themselves; they are always ready to use words to “get a gasp.” If Trump ever used words to render reality, I never heard it. Like a committed pragmatist, he uses words to influence his listeners and accomplish his goals. We Americans, natural pragmatists, understand this in a way that no European electorate ever could. His way of using language is all too often ours, which is one of the reasons so many of us are receptive to it.’

(…)

‘It has been said many times that Trump was—in his own bizarre fashion—a postmodernist president. Those who say this generally use the term “postmodern” loosely. They mean that Trump cared nothing for tradition, had no regard for truth, that he lied all the time. But Trump is far better understood as our first pragmatist president. Trump knew—and knows—that Truth has gone on vacation; his acolytes know it, too. They are not nihilists, as they are often labeled, for they clearly do value something. And they are not deconstructionists, for they are prepared to latch onto pragmatic truths that will get them what they want.

Trump’s language is, or seeks to be, performative. He speaks to advance his cause and confound his enemies. To achieve this, he will say virtually anything. His followers—disillusioned people who have been stripped of ideals—are responsive to his reckless pragmatism and employ it themselves; they are always ready to use words to “get a gasp.” If Trump ever used words to render reality, I never heard it. Like a committed pragmatist, he uses words to influence his listeners and accomplish his goals. We Americans, natural pragmatists, understand this in a way that no European electorate ever could. His way of using language is all too often ours, which is one of the reasons so many of us are receptive to it.’

(…)

‘I listened to Rorty with great respect for his intellect and his imagination, but also with some skepticism, which has grown over the years. Pragmatists like Whitman want things that are, to me at least, worth wanting. He wanted freedom, joy, the possibility for people of all types to get together and have a good time. He used his words to try to make that happen. Trump, as pragmatic as anyone, largely wants things that are not worth wanting: division, suspicion, hatred among Americans, personal power. Trump is about as close to being Whitman’s hateful double as possible. But they are both inheritors of American pragmatism.

Rorty praises George Orwell for teaching us that “nothing in the nature of truth, or man, or history” can prevent a scenario in which fascism triumphs. To the pragmatist, free and open democracy is no more true and authentic than tyranny. There is no special Truth existing on high that you can appeal to when the fascists are winning and you want to set your fellow citizens right. There’s just your vision, your interpretation, which has no more intrinsic validity than that of the fascists.’

(…)

‘They are also risky: Socrates, Jesus, and Hector all died for their ideals. But ideals fill the idealist with a certain kind of joy, a joy that is not identical to happiness. I’m not sure whether humans have souls, but I do believe that when an idealist pursues an ideal, she leaves what I call the realm of Self. She leaves the state where what matters most are our desires and their fulfillment, and enters another state, which I call the state of Soul.’

(…)

‘We need solid ground. Thousands of years of history and culture show us what humans at their best value: high ideals, energetically pursued. Truth has been on vacation long enough—it’s time to put it back to work.’

Read the article here.

This is interesting enough. Sometimes a bit of a variation on the old complaint that Foucault and other thinkers inevitably helped the extreme-right, maybe not because of their appetite for pragmatism but because it became general knowledge that truth, capital T or nor, is always also a product pf the power games people are playing.

And he is wrong about Socrates. Socrates also died because he was vain and stubborn, he should read what Nietzsche about Socrates before turning the famous philosopher in a contemporary hero.

Democracy is by nature pragmatism at work, it’s the realization that people not only have different interests but also have different ideals.

The problem is that ideals can be found in the roots of totalitarian regimes, in the roots of many terrorist movements. That doesn’t mean that all ideals are suspect, but idealism is no guarantee that the Truth will come back from its vacation.

Quite the opposite, the belief that idealism will save us means that the truth will prolong its holiday.