On Spain, socks and women travel writers – Sara Wheeler in TLS:

‘Madrid, 1679. At Doña Teresa Pacheco’s toilette, a wrinkled retainer swigs rosewater, clenches her teeth and shoots the fragrant liquid into her mistress’s face so it falls “like rain”. The author of Travels into Spain, Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, who is present at the levée, doesn’t fancy this ritual. She avoids judgement, insisting “everything has a good and a bad side”. But she is as human as the rest of us, and many of her observations have matured into travellers’ clichés: food is too spicy, tradesmen are lazy and “everyone is a crook”.

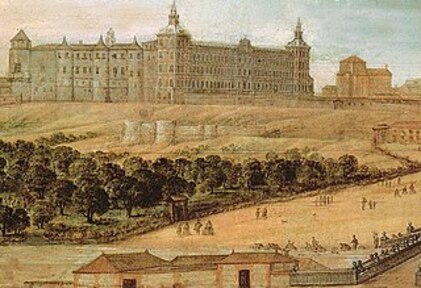

Born in Normandy of noble parentage, at thirteen Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville (1652–1705) married the old Baron d’Aulnoy. Within five years she had given birth to three infants, two of whom died, and was pregnant with a fourth. The husband was violent and the baronne eventually fled back to her mother. This latter enjoined her lover in a plot to entrap the baron into the capital offence of he triple-decker, this edition of which Verdier has superlatively translated, edited and annotated, was “the most important source of information on Spain for two centuries”. It remains a gripping account of early-modern Spain and the female gaze. D’Aulnoy and one of her daughters crossed the border from France on a litter, a kind of sedan chair. Their retinue, which included a cook, was “so big that we could have rivalled those famous caravans that go to Mecca”. Twenty men cleared deep Pyrenean snow to facilitate their passage, and villagers rang bells “ceaselessly” to direct the party to the inn.

Following the established epistolary form, the book consists of fifteen letters home to a female cousin. The first seven relate the three-week journey from Bayonne to Madrid, the next seven describe events in the capital. A final letter, dated a year later, concludes in 1680, after Marie-Louise d’Orléans arrives at court to marry Carlos II. The princess’s bed, d’Aulnoy reveals, is laid with fourteen mattresses.

. “Biographers”, writes Gabrielle M. Verdier in her introduction to Travels into Spain, “disagree on the extent of d’Aulnoy’s involvement in the plot against her husband.” Anyway, it failed. The still-young bride vanished. Nobody knows exactly what she did, except travel to Madrid in the dying years of the Habsburgs. In 1685 she entered a French convent and began to write.’

(…)

‘One enflamed lover shins up a wall to enter the bedchamber where his sweetheart lies with her sleeping husband. His work done, and having shinned down again, he must navigate the contents of chamber pots being emptied in the streets, returning to his conjugal home pungent and besplattered. Widening her lens, d’Aulnoy delivers set-piece tableaux. In Holy Week the Duke of Vejar’s sixty knights process through the inky night, each with hundreds of pages bearing white wax torches. When this ambulant carnival meets another such, the pugnacious men scorch each other’s beards. Elsewhere someone “scrapes” an old guitar in a blackened kitchen and sings “like a hoarse cat” while haunches dangle over the central fire.’

(…)

‘Her encounters yield four long first-person love stories (“Based on everything I’ve been told”, she writes, “I’d easily believe that Love was born in Spain”). In the first the author is dozing abed when she hears, behind a flimsy inn partition, the wails of two young beauties facing a forced marriage. Soon two men storm in, “swords in hand”, on a mission to rescue the damsels. Other stories revolve round mistaken identity, disguise and cross-dressing. Many of d’Aulnoy’s characters are composites. Whose aren’t, in a travel book? As Verdier notes, “the men and women in these pages are unforgettably real if not factually so”.

Did she make the whole thing up, though? Challenges arose in the nineteenth century, and in 1926 a prominent Hispanist announced in print that “Madame d’Aulnoy never went to Spain”. The editor concludes, convincingly, to my mind, that the book is almost certainly a mixture of “astute observation and adroit compilation”. The travel genre is by nature a hybrid. Verdier gives context. “More ancient than the novel, travel accounts proliferated with printed books in the early modern era”, and regularly included “allegories, imaginary voyages, and forgeries”. She refers to the “ancient tradition” of the “travel liar”.’

(…)

‘Women travel writers are more than that, and they showed it when borders named and unnamed fell for them in the twentieth century. Kansas-born Irene C. Peden, now ninety-seven, was the first female scientist to work in the Antarctic interior. She was an associate professor of engineering as well as a writer, and she went to conduct research into the lower ionosphere. It was 1970. The admiral commanding the South Pacific Fleet (the US Navy operated polar logistics) objected vociferously to the inconvenience of mixed conveniences. Decades later Peden wrote about the toilet problem. “I was staggered to find”, she said, “that the first woman astronaut, Sally Ride, had to put up with the same stuff.” The Spanish Civil War and the Second World War opened a man’s world to women correspondents. Clare Hollingworth (1911–2017) broke the story that Germany was about to invade Poland after she observed tanks, armoured cars and field guns mustering in the valley below the frontier road from Hindenburg to Gleiwitz. Here, too, men were reluctant to let the lavatory issue go. Lieutenant Colonel Philip Astley, director of press relations at British HQ in Cairo in 1941, repeatedly briefed the War Office on the “unacceptable inconvenience” of mixed facilities for female correspondents in the press corps. When a woman reporter visited one British battalion in the desert, he wrote, the problem was so acute that not a single soldier was able to open his bowels, to the agonizing extent that “at least three hundred men were unmoved for three days”.’

(…)

‘The second half of the twentieth century allowed women to expand the form. Noo Saro-Wiwa, in Looking for Transwonderland (2012), asked why her Nigerian homeland rarely features on a tourist itinerary. So she went home as a tourist, aiming to “uncover layers of history we don’t know”. Sanmao (1943–91), raised in Taiwan but born in Chongqing (her birth name was Chen Mao-ping), travels in Stories of the Sahara and other books at a walking pace because, she says, the speed is suitable for registering one’s surroundings. Sanmao’s travel writing made her one of the first media stars in China, and she achieved her goal of broadening horizons. In 2018, on the anniversary of her death, a commemoration posted on the social media platform Weibo by the Communist Youth League received more than 100,000 comments.

Women have written books about pulling sledges over frozen wastes, but on the whole we are indifferent to seeing how dead we can get. Close observation and specificity, essential characteristics of the genre, are at home in the home. And, as Verdier notes of the author of Travels into Spain, “her narrator can enter women’s private spaces and have intimate conversations about matters they would never reveal to their husbands and lovers”. A man would not have witnessed a retainer expectorating rosewater at a levée. I learnt more about the lived experience of Pinochet’s regime around Chilean kitchen tables than I ever did from a book. I remember a woman of my age cradling a baby and looking out of the window at Andean foothills rising into a clear blue sky. “Mi mamá”, she told me, remembering the night the knock came, when she was ten, “se enojó porque no se puso los calcetines”. Her mother was annoyed with her husband, my interlocutor’s father, for not putting on his socks before Pinochet’s goons took him. They never saw him again.’

Read the article here.

The travel liar should be given more credit.

Ryszard Kapuściński was to a certain extent a travel liar. (When I was 19 or 20 I interviewed Kapuściński in Amsterdam. He was slightly nasty. He said among other things, ‘I write my books, I don’t read them.’) But there is of course no connection between the humble craft of travel lying and nastiness.

It's very well possible that a man would not have noticed a ‘a retainer expectorating rosewater at a levée.’ I wonder how I should imagine this. Did people gargle with rose water?

And I thought that love was invented in Italy, but Spain will do as well.

The anecdote about Chile has not much to do with Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy or Spain but is insightful.

If you expect a knock on the door sleep with your socks on. (Cold bedrooms could be a reason to sleep with your socks on as well.)

‘