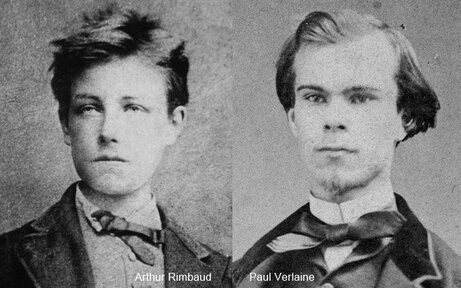

On translation and Rimbaud – Michael Wood in LRB:

“Speaking of his remarkable version of Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations, John Ashbery said: ‘I myself try to be very literal, and I frequently use cognates even when they might sound a little strange in English.’ ‘Are there times when that doesn’t work?’ his interviewer, Claude Peck, asked. Ashbery replied without hesitation: ‘Oh sure, on every page, many times.’ A great picture of the joys and travails of translation. Rimbaud is an intriguing case in this context, because although the words of his poems can be translated more or less literally, they rarely have literal referents. They are too busy delivering what he calls his phantasmagorias. There is a subtle precision in his saying he is a master in (‘maître en’) such things rather than of them, which Mark Polizzotti catches well with his ‘I am a master at phantasmagoria.’”

(…)

“Has anyone ever been in hell for just one season? Do flowers, even magical ones, buzz like bees? What can it mean to say that when you were twelve years old and locked in an attic you illustrated the human comedy? Or that one night at a party you met all the women of the old painters? These moments are all present in Polizzotti’s engaging selection of new translations, which includes, as he says, ‘about half of the major verse poems, half of Illuminations and the entirety of A Season in Hell, along with most of the known letters by Rimbaud up to 1875’. Polizzotti’s aim, he says, is ‘to provide an approachable, and I hope enjoyable, introduction to Rimbaud’s work’, and this project is a distinct success. It does leave, and perhaps can only leave, an interesting question hanging in the wind. Who or what was Rimbaud?”

(…)

“ It could be a circus that has got out of hand, or just a slice of life: Chinois, Hottentots, bohémiens, niais, hyènes, Molochs, vieilles démences, démons sinistres, ils mêlent les tours populaires, maternels, avec les poses et les tendresses bestiales ... Maîtres jongleurs, ils transforment le lieu et les personnes, et usent de la comédie magnétique. Les yeux flambent, le sang chante, les os s’élargissent, les larmes et des filets rouges ruissellent.

Chinese, Hottentots, Bohemians, simpletons, hyenas, Molochs, old dementias, sinister demons, they mix popular, maternal numbers with poses and bestial tenderness ...Master jugglers, they transform places and people, use magnetic comedy. Eyes flame, blood sings, bones expand, tears and crimson trickles flow down.

I especially like the idea of bestial tenderness and magnetic comedy. And I am also inclined to see the final line as a signature for almost all of Rimbaud’s work: a savage parade that he controls, or says he controls.”

(…)

“And all these remarks point to one of Rimbaud’s favourite and most powerful literary moves: the flight into a mythology that seems less mythological every minute, not literal but definitely real. There is, for example, the Christian framework of hell and sin. Rimbaud addresses the devil as ‘dear Satan’, a personage who momentarily becomes the reader, since ‘these hideous pages from my notebooks of the damned’ are ‘torn out’ for him. There is the colonial framework in which the natives with whom Rimbaud identifies have ‘always been of inferior race’. Later on he dramatises the recurring invasive moment: ‘The white men have landed. Cannons! We must submit to baptism, wear clothes, go to work.’ And there is also the myth of what Rimbaud calls ‘the decline of the Orient’. Everything the West does is far from ‘the thinking and wisdom of the East, the primary fatherland. Why a modern world at all, if it invents such poisons!’ Rimbaud rebukes both clerics and philosophers, who don’t see what they are missing, don’t realise that their ostensible progressive gain is all loss. ‘You are in the West, but you’re free to live in your East, however ancient you need it to be.’ We see why the Beats loved Rimbaud.

But we also need to see the desperation in such an invitation to freedom, and Rimbaud explicitly invites us to do this. He had, he insists in the last section of A Season in Hell, entitled ‘Farewell’, ‘called myself magus or angel’, but has now ‘crashed back down to earth’ and earned a new name: ‘peasant’. Nothing wrong with being a peasant, of course, even if you would rather be a magus or an angel. But for many of us, much of the time, any single name is going to be wrong.”

(…)

“Un beau matin, chez un peuple fort doux, un homme et une femme superbes criaient sur la place publique. ‘Mes amis, je veux qu’elle soit reine!’ ‘Je veux être reine!’ Elle riait et tremblait. Il parlait aux amis de révélation, d’épreuve terminée. Ils se pâmaient l’un contre l’autre.

En effet ils furent rois toute une matinée où les tentures carminées se relevèrent sur les maisons, et toute l’après-midi, où ils s’avancèrent du côté des jardins de palmes.

One fine morning, in the country of a very gentle people, a magnificent man and woman were shouting in the public square. ‘My friends, I want her to be queen!’ ‘I want to be queen!’ She was laughing and trembling. He spoke to their friends of revelation, of trials completed. They swooned against each other.

In fact they were regents for a whole morning as crimson hangings were raised against the houses, and for the whole afternoon, as they moved towards groves of palm trees.

‘Regents’ is not a literal translation but it does add to the sadness of the story, suggesting that even fulfilled wishes may have to make do with replacements.”

Read the review here.

Seasons in hell are very well possible. The twentieth century is filled with seasons in hell and even before that we knew that it was possible to buy return tickets to hell. (It has not always been necessary to buy a ticket, very often the participants got a free ticket.)

“The flight into a mythology that seems less mythological every minute,” – isn’t that what literature should strive to do? Especially, since the facts are mythological enough.

We are left with bestial tenderness, and cruelty without any tenderness, needless to say.

But we can shout: "Mes amis, je veux qu’elle soit reine!’ ‘Je veux être reine!"

Our playfulness and dignity are inseparable.