On boxing and writing – James Marcus in TLS:

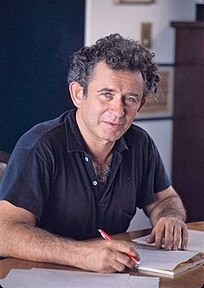

‘Mailer, born a century ago on January 31, 1923, always regarded boxing as a metaphor for art. Like his hero Ernest Hemingway, he treated writing and fighting as interchangeable agonies, with clear winners and losers. “People who write books take as much punishment as prizefighters”, he insisted on television in 1971, “and one of them has to be the champion.” To his fellow guests, including Gore Vidal, whom he’d head-butted in the green room before the show, he added: “I’m going to be the champ until one of you knocks me off”.’

(…)

‘ For decades it mattered what Mailer thought about Vietnam, JFK, Hollywood, race or feminism. He was the nation’s wild-eyed diagnostician; even his nuttiest ideas helped set the terms of debate. Yet his zest for combat was inseparable from a kind of religion of masculine bluster, which in Mailer’s case was sometimes merely rhetorical, but tended to erupt into physical violence.

He has not been cancelled. Much of his enormous output remains in print, and a work such as The Executioner’s Song, which won him the Pulitzer prize in 1980, continues to shift 1,000 or so copies every year. Still, his star has dimmed. Penguin Random House, which had been contemplating a new anthology of Mailer’s nonfiction to mark his centenary, scuttled the project last year. The reasons were a little vague. Either Mailer’s 1957 essay “The White Negro”, with its hipster poppycock and patronizing view of Black Americans, was now too much for contemporary readers to swallow, or the anticipated financial returns were too meagre.

Which is not to say his centenary will pass unmarked. At least four books have been issued in recent months, all of them meant to celebrate Mailer’s life and art, which were joined at the hip. Let’s start with Richard Bradford’s Tough Guy. Bradford, who has published more than thirty books, including warts-and-all portraits of Patricia Highsmith and Hemingway, likes to engage with turbulent personalities. With Mailer, he has hit the jackpot. It was Vidal, in an affectionate 1960 essay, who suggested that his old friend had a “nice but small gift for self-destruction”. That was an understatement. Mailer’s gift for self-destruction was vast, iridescent, iceberg-sized, and Bradford spends much of his book trawling through the wreckage.’

(…)

‘The Naked and the Dead has now been reissued by the Library of America in a handsome edition that includes a generous selection of the letters Mailer sent to Bea and various other relatives during his military service. These were notes for the novel he already knew he was writing the minute he set foot on the Philippine island of Luzon, where he spent most of the war. They were his seed corn, his skeletal material, sometimes quoted almost verbatim.

Yet the novel never feels like a scarecrow production, patched together from blurry V-mails to the author’s wife. It is a big, vivid, grimy, incessantly curious narrative, punctuated with scenes of combat, but much more focused on the quotidian misery of men at war, whose frequently boring and bureaucratic tasks take on a strange heroism by virtue of their proximity to death. It is also, as Bradford points out, “a book about America, a nation whose tribalist, class-based and psychosexual tensions are crystallised in US servicemen sent somewhere else, somewhere particularly alien”.

The Naked and the Dead is a young man’s book – one Mailer himself later referred to as “the work of an amateur”. It is flawed. Following the classic formula, the soldiers represent a schematic cross-section of American life, and you can almost see Mailer checking off the boxes: rich and poor, Jew and Gentile, loafer and libertine. His excursions into the childhoods of his characters are particularly creaky. Still, the novel remains a marvel of postwar naturalism, with plenty of room for Mailer to dive beneath the hardscrabble surface. When he writes of one character feeling “a sense of mystery and discovery as if he had found unseen gulfs and bridges in all the familiar drab terrain of his life”, the elation is Mailer’s, and ours too.’

(…)

‘Many writers would have stopped there. Twenty years in the spotlight, a few trophies for the mantelpiece, a blissful retirement. Not Mailer: his madcap progress continued until his death in 2007. There were more books, more wives, more children, more real estate, more polemics. There were also more physical altercations. Some, like his ear-biting tussle in the grass with the actor Rip Torn, are preserved on film. The most momentous, of course, had taken place in 1960, and represented the nadir of Mailer’s existence: the stabbing of his second wife, Adele Morales, during the drunken launch of his first mayoral campaign.

There is no excusing or minimizing this atrocious act, which led to a suspended sentence for felonious assault and landed Mailer in the psych ward at Bellevue for seventeen days. Morales, who survived the attack, made an attempt to reconcile with Mailer, but divorced him in 1962. By then, however, his brief period as a social pariah had ended and he was allowed to resume his place in the cultural landscape.

The willingness of Mailer’s peers to forgive (or at least tolerate) this assault seems old-fashioned in the worst sense. Yet it’s also true that he elicited this response more generally, even from people inclined to view him with extreme scepticism. Elizabeth Hardwick, for example, noted the “large proportions of Mailer himself, his confidence and intrepidity, his florid pattern of experience, his disasters met with an almost erotic energy of adaptation”. There was an affection, even a kind of tenderness, for his intermittent lunacy – as if the proprietors of the china shop were ultimately charmed by the bull.’

(…)

‘Who knew, for example, that Didion considered Mailer “one of the few people who can write about sex without embarrassing me”, or that Mailer’s massive journal of the mid-1950s, mostly composed while he was stoned out of his gourd, owed so much to Jungian principles? The essays are scholarly in tone, even a little diffident, which seems like a mismatch – doesn’t Mailer dictate a more bare-knuckles approach? But perhaps Begiebing is onto something. When he interviewed Mailer in 1983, this most aggressive of writers suggested that he might be a passive vessel after all: “If there’s anything up there or out there or down there that is looking for an agent to express its notion of things, then, of course, why wouldn’t they visit us in our sleep? Why wouldn’t we serve as a transmission belt?” Mailer taking dictation from the divine is a funny thought. No doubt he would have considered it a conversation between equals. But before we get too carried away with this picture of him as a recording angel, a gentle intermediary between eternity and the reader, we should bear in mind a detail from J. Michael Lennon’s deathbed chronicle. Mailer was buried in his boxing regalia – a fighter to the end.’

Read the article here.

The writer as transmission belt might be perfectly accurate.

Coetzee and Milosz hinted at the writer as ‘secretary of the invisible.’ Mailer clearly wasn’t fit to become secretary, he was too eager to listen to himself.

I would say that forgiveness is not necessarily old-fashioned, that our contemporary unwillingness to forgive is more a sign of how we view society: as a collection of potential or real victims. In order to keep this image intact, all perpetrators must be removed.