Again on Schulz – Joshua Cohen in NYT:

‘Bruno Schulz was a gnomish, cockeyed Polonophone Jew whose writing gave sophisticated expression to the wondrous vagary and uncertainty and foreboding of childhood, without forcing it to — actually, without letting it — grow up. His two volumes of fiction — the sum total of his surviving work save a few scraps that, given Schulz’s focus on youth, one hesitates to call juvenilia — are rife with how small it can feel to be small; they are claustral with the creeping tensions and melancholy of adult domesticity, and slyly attentive to the vulnerability of boredom that can, suddenly, crashingly, turn one’s head to sex.’

(…)

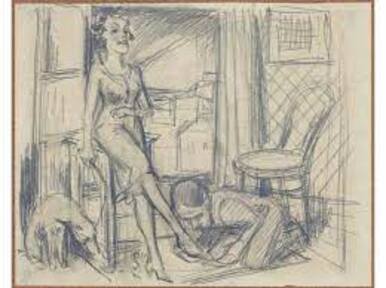

‘By night Schulz wrote his fictions and illustrated them with erotic sketches and caricatures charged with a louche sadomasochistic energy, many of them devoted to foot-and-shoe worship and the female domination of men. It was this work that attracted the deranged patronage of Felix Landau, an SS officer and the self-proclaimed Judengeneral, or “General of the Jews,” of Drohobych, who adopted Schulz as his Leibjude, his “personal Jew,” and ordered him to execute several murals throughout the town, including a capacious painting for the SS casino and some wall decorations for the children’s room at Landau’s own requisitioned home. Despite Schulz’s ostensibly protected status, which allowed him to survive the ghettoization and initial deportations and liquidations of Drohobych, he was shot to death on the street in the winter of 1942 — probably by an SS officer who was a rival of Landau’s.’

(…)

‘In that book as in this one, Balint excels at distinguishing the possible ownership of artifacts from the impossible ownership of legacies, and demonstrates with sensitivity how in the clash between so-called intellectual property rights and so-called moral rights, the only sure loser is the artist himself, especially if he is no longer around to defend (or define) himself. Tracing the idea of possession through both its economic and demonic implications, Balint assembles a motley group portrait of Ukrainian cultural legations and Drohobych council members, Polish envoys and German curators, each with a career to tend and opinion to advance: One thinks the murals should be kept in a museum in Warsaw; another thinks they should be kept in situ, and Villa Landau converted into a museum.’

(…)

‘As the Holocaust recedes into the unremembered past with the deaths of its final surviving victims, it’s incumbent upon Jews, but not only upon Jews, to ask what its tragedy should or could still justify: A Drohobych emptied of all signs of its former Jewishness? A Ukraine stripped of a vital, centuries-long strain of its history? Or what about a child’s room demolished in the occupied territories, bearing its own murals of fragile dreams and tentative magics? “Somewhere along the line,” Balint writes, “in the truceless contest between peoples and in the struggle to shape their afflicted and unappeased pasts, our admission into Schulz’s own mythmaking has become occluded.”’

Read the article here.

Boredom can lead to sex.

How much sex there is in the stories of Schulz? More desire and subdued desire than sex, but in literature that’s always better.

Cohen is not too fond of the literature of Schulz, which I can understand. The smallness of being small is a bit bigger than depicted here, and I myself am not the biggest Schulz-lover.

How much Schulz or Jewishness we need in Drohobych is almost a touristy question, How and how deep the state of Israel became involved in the legacy of Kafka and Schulz is material for more than one novel.

It’s interesting which Jewish legacy the state of Israel is interested in.

I cannot imagine the state of Israel being interested in the legacy of Walter Benjamin but maybe I’m wrong.