On Felix Salten – Kathryn Schulz in The New Yorker:

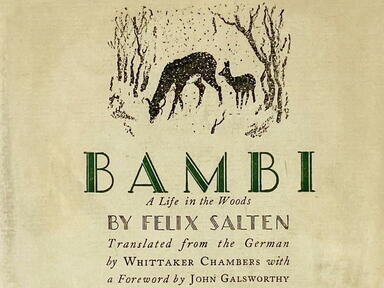

‘As that suggests, “Bambi” the book is even darker than “Bambi” the movie. Until now, English-language readers had to rely on the Chambers translation—which, thanks to a controversial copyright ruling, has been the only one available for almost a century. This year, however, “Bambi: A Life in the Woods” has entered the public domain, and the Chambers version has been joined by a new one: “The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest” (Princeton), translated by Jack Zipes, with wonderful black-and-white illustrations by Alenka Sottler. Zipes, a professor emeritus of German and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota, who has also translated the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, maintains in his introduction that Chambers got “Bambi” almost as wrong as Disney did. Which raises two questions: How exactly did a tale about the life of a fawn become so contentious, and what is it really about?

Felix Salten was an unlikely figure to write “Bambi,” since he was an ardent hunter who, by his own estimate, shot and killed more than two hundred deer. He was also an unlikely figure to write a parable about Jewish persecution, since, even after the book burnings, he promoted a policy of appeasement toward Nazi Germany. And he was an unlikely figure to write one of the most famous children’s stories of the twentieth century, since he wrote one of its most infamous works of child pornography.

These contradictions are nicely encapsulated by Beverley Driver Eddy in her biography “Felix Salten: Man of Many Faces.” Born Siegmund Salzmann, in Hungary in 1869, Salten was just three weeks old when his family moved to Vienna—a newly desirable destination for Jews, because Austria had lately granted them full citizenship. His father was a descendant of generations of rabbis who shook off his religious roots in favor of a broadminded humanism; he was also a hopelessly inept businessman who soon plunged the family into poverty. To help pay the bills, Salten started working for an insurance company in his teens, around the same time that he began submitting poetry and literary criticism to local newspapers and journals. Eventually, he began meeting other writers and creative types at a café called the Griensteidl, across the street from the national theatre. These were the fin-de-siècle artists collectively known as Young Vienna, whose members included Arthur Schnitzler, Arnold Schoenberg, Stefan Zweig, and a writer who later repudiated the group, Karl Kraus.

Salten was, in his youth, both literally and literarily promiscuous. He openly conducted many affairs—with chambermaids, operetta singers, actresses, a prominent socialist activist, and, serially or simultaneously, several women with whom other members of Young Vienna were having dalliances as well. In time, he married and settled down, but all his life he wrote anything he could get paid to write: book reviews, theatre reviews, art criticism, essays, plays, poems, novels, a book-length advertisement for a carpet company disguised as reportage, travel guides, librettos, forewords, afterwords, film scripts. His detractors regarded this torrent as evidence of hackery, but it was more straightforwardly evidence of necessity; almost alone among the members of Young Vienna, he was driven by the need to make a living.’

(…)

‘Salten maintained that, despite his own affinity for hunting, he was trying to dissuade others from killing animals except when it was necessary for the health of a species or an ecosystem. (That was less hypocritical than it seems; Salten despised poachers and was horrified by the likes of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who boasted of killing five thousand deer and was known to shoot them by the score as underlings drove them into his path.) But authors do not necessarily get the last word on the meaning of their work, and plenty of other people believe that “Bambi” is no more about animals than “Animal Farm” is. Instead, they see in it what the Nazis did: a reflection of the anti-Semitism that was on the rise all across Europe when Salten wrote it.’

(…)

‘It’s tempting to read those lines, too, as a commentary on the Jewish condition, if only because—to this Jew’s ears, at least—they have the feel of classic Jewish dark humor: realistic, linguistically dexterous, and grim. Yet no one alive today can regard such a sentiment as exclusive to any subgroup. It is simply a way of seeing the world, one that can be produced by circumstance, temperament, or, as in Salten’s case, both. Reading him, one suspects that the conventional interpretation of his most famous work is backward. “Bambi” is not a parable about the plight of the Jews, but Salten sometimes regards the plight of the Jews as a parable about the human condition.’

Read the article here.

Salten was a bit hesitant to condemn the book burnings, but to call him an appeaser which is just short of a collaborator does injustice to him.

He was haunted by the Nazi’s, he lost almost everything after the Anschluss, that he felt more Austrian than Jewish was common at that time. See what Améry wrote about becoming Jewish thanks to the Nazi’s. Or the delightful and subtle anti-Semitism that can be found in the criticism of Kraus.

Salten stated from Switzerland, where he was not treated well, that after Hitler would be defeated he would start travelling again, but he would never go back to Austria.

I would not say that ‘A Viennese Prostitute’ by Josephine Mutzenbacher is work of child pornography. Read it yourself, you can order it here.

Salten never admitted that he wrote it, and some scholars claim that he is not the author of this book. I think he is, but my arguments are intuition.

It’s a bit strange that these details are omitted in the article.

Also, he came from a much poorer background than most other authors in his surroundings, Arthur Schnitzer was an aristocrat compared to Salten. This could explain his decision to write reviews for money instead of books, his obsession with money. And so many great authors were obsessed with money.

Here it seems a strategy to belittle him. He chose money over true art.

The plight of the Jews as a parable for the plight of mankind is a very accurate description of Salten’s world view.

(I wrote a preface for the Dutch translation of 'Bambi'.)