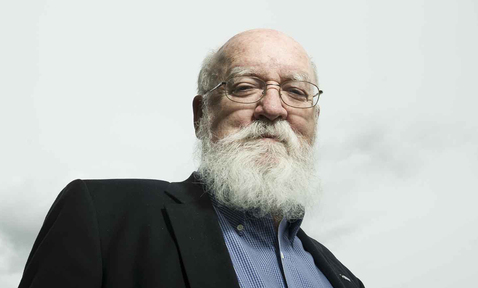

On Dennett -Nigel Warburton in TLS:

‘But, as he [Daniel Dennett] points out, luck is in part what you make of the hand you are dealt. He knows he has played his well enough, though he admits that he has a lazy streak, and a degree of vanity, and is easily sidetracked by crosswords and Scrabble.

Perhaps I’m biased, but I think we are lucky that Dennett exists. His early book Brainstorms (1978) and the collection of essays and philosophical fiction The Mind’s I, which he co-edited with the polymath Douglas Hofstadter back in 1981, enriched the lives of many philosophy undergraduates in the early 1980s – mine included. Not only did we get to read about the nature of the mind, we were also introduced to the stories of Jorge Luis Borges and Stanisław Lem. These books were up there with other favourites, Thomas Nagel’s Mortal Questions, Peter Singer’s Practical Ethics and Jonathan Glover’s Causing Death and Saving Lives. Dennett’s particular skill as a writer was to make reading about the philosophy of mind, which could be technical, dull and hard to follow, into a joy.’

(…)

‘He even divulges a useful technique for staying awake during boring presentations. (Listen out for the speaker saying a word containing the letter “a”. Write it down. Then do the same with “b”, and so on through the alphabet. Even if you don’t get to “z”, you’ll seem to be paying attention and you’ll look as if you’re taking notes. Genius!)’

(…)

‘Dennett emphasizes his good fortune in this memoir, and what he’s made of it, but he has been unlucky too. Like Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre, he lost his father early, when he was just five. Dennett senior, a spy who worked for the forerunner organization of the CIA in Beirut, died when his plane on a mission in Ethiopia crashed in what probably wasn’t an accident. Dennett adored his father. Sartre credited his early loss of his father for the absence of a superego that liberated him from conventional restraints. Perhaps something similar happened to Russell, but nothing like that seems to have occurred in Dennett’s case. From the evidence of this memoir at least, he has led a full, interesting and varied life, but has never been wild and, as he confesses, avoided most of the excesses of the 1960s.’

(…)

‘But a conversation with Robert Nozick, a philosopher renowned for his speed of thought, proved reassuring. Nozick admitted that, though he grasped complex ideas with little effort, he felt he missed things as a result; the philosophers who struggled to understand were often the ones who saw the problems that he glided past.

Dennett has spent most of his subsequent academic career at Tufts University, which, as he tells us, lies at the apex of an equilateral triangle that has as its base a line drawn between Harvard and MIT. But he has travelled the world discussing his ideas, and much of the book is devoted to explaining what he has learnt from his interactions with a range of extraordinary thinkers, including John Maynard Smith and Richard Dawkins. At the heart of his approach to philosophy is the theme that has animated the subject at least since Plato: the relationship between appearance and reality.’

(…)

‘Dennett maintains that we do in fact have the only kind of free will worth wanting, but that this is not in conflict with causal explanations. He is a compatibilist, like his hero Hume, and argues that we need to think of free will as absence of coercion combined with the exercise of autonomy (internal self-control). Freedom of the will describes the source of our decision-making, but it doesn’t in any way conflict with our scientific understanding of the world, and is in fact compatible with and dependent on it.’

(…)

‘Yet, as St Ludwig wrote: “The philosopher is not a citizen of any community of ideas. That is what makes him a philosopher”.’

Read the article here.

Dennett’s advice how to get through boring presentations and speeches is genius. Unfortunately, you cannot always take notes.

The minimalist take on free will is pleasant as well.

Anybody who has even a limited amount of self-control has a free will. This makes us nothing more than an upgraded dachshund – but that’s fine as well. After all, better an upgraded dachshund than a dachshund. Not all Buddhists will agree but that’s also, let’s say free will.