Zoë Heller in the Times on authors reviewing other authors:

"Before we rebuke these writers for their intellectual cowardice, we ought to acknowledge the genuine difficulty of the task they shirk. The literary world is tiny. The subgroup represented by novelists is even tinier. If you’re an author who regularly reviews other authors, the chances of running into a person whose novel you have criticized are fairly high. (All the higher, if you happen to live in New York City or some other center of ambition.) It may not be the worst thing in the world to find yourself side by side at a cocktail party with the angry man whose work you described as mediocre in last Sunday’s paper, but the threat of such encounters is not a great spur to critical honesty.”

The fear of an angry author confronting you with your literary opinions at a cocktail party, while you thought you could enjoy a canapé, can be easily avoided: don’t go to cocktail parties.

(And a wise author would never confront the reviewer at a cocktail party.)

But there are other and more dangerous enemies of critical honesty: snobbery, lack of knowledge, the desire to be original, the desire to take revenge, misogyny and ideology, to name just a few.

Adam Kirsch answers Zoë Heller:

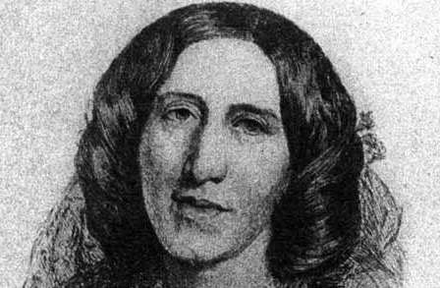

‘In 1856, two years before she published her first book of fiction, George Eliot wrote a scathing essay on “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” in which she pre-emptively declared war on the low expectations Victorian readers had for novels by women. In the same way, David Foster Wallace blasted Norman Mailer, John Updike and Philip Roth as “Great Male Narcissists”; a couple of years later, he published “Brief Interviews With Hideous Men,” his own fictional inquiry into pathological male narcissism. Henry James dismissed even “War and Peace” as a “loose, baggy monster,” in order to justify the self-conscious formalism of his own books.

For all these writers, criticism was a way of understanding themselves, of discovering how they did and did not want to write. It was also a means of educating the public, preparing readers for the revolution in taste they wanted to sponsor. Perhaps a writer can’t be great without a touch of this kind of aggression, this intolerance of artistic error.’

(Read the complete exchange here.)

I’m not convinced that authors should engage in criticism. In Germany, to name just a country, most criticism is done by professional reviewers. (Whether this is better or not is open for debate.)

It’s very well possible to be a great novelist and a lousy essayist. Quite a few writers have nothing interesting to say about their own books nor about novels by other authors.

And yes, perhaps genius and aggression go hand in hand, as Adam Kirsch suggests, but nowadays this kind of aggression is hardly accepted.

Where literature becomes a career opportunity, criticism as politics is not much more than the art of the possible.