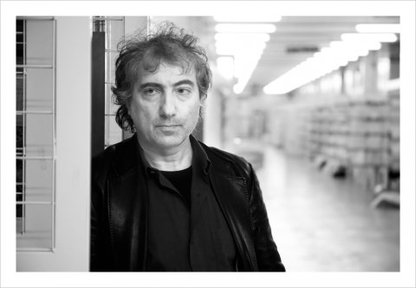

Adam Phillips on self-criticism, ambivalence and consciousness:

“Lacan said that there was surely something ironic about Christ’s injunction to love thy neighbour as thyself – because actually, of course, people hate themselves. Or you could say that, given the way people treat one another, perhaps they had always loved their neighbours in the way they loved themselves: that is, with a good deal of cruelty and disregard. ‘After all,’ Lacan writes, ‘the people who followed Christ were not so brilliant.’ Lacan is here implicitly comparing Christ with Freud, many of whose followers in Lacan’s view had betrayed Freud’s vision by reading him in the wrong way. Lacan could be understood to be saying that, from a Freudian point of view, Christ’s story about love was a cover story, a repression of and a self-cure for ambivalence. In Freud’s vision we are, above all, ambivalent animals: wherever we hate we love, wherever we love we hate. If someone can satisfy us, they can frustrate us; and if someone can frustrate us we always believe they can satisfy us. And who frustrates us more than ourselves?”

(…)

“The loathing which should drive [Hamlet] on to revenge,’ Freud writes, ‘is replaced in him by self-reproaches, by scruples of conscience, which remind him that he himself is literally no better than the sinner whom he is to punish.’ Hamlet, in Freud’s view, turns the murderous aggression he feels towards Claudius against himself: conscience is the consequence of uncompleted revenge. Originally there were other people we wanted to murder but this was too dangerous, so we murder ourselves through self-reproach, and we murder ourselves to punish ourselves for having such murderous thoughts. Freud uses Hamlet to say that conscience is a form of character assassination, the character assassination of everyday life, whereby we continually, if unconsciously, mutilate and deform our own character. So unrelenting is this internal violence that we have no idea what we’d be like without it. We know almost nothing about ourselves because we judge ourselves before we have a chance to see ourselves.”

(…)

“Conscience is intimidating because it is intimidated. We have to imagine not that we are cowardly, but that we have been living by the morality of a coward; the ferocity of our conscience might be a form of cowardice. But what other kind of morality might there be? If we have been living by a forbidding morality, what would an unforbidding morality look like? There are moralities inspired by fear, but what would a morality be like that was inspired by desire? It would, as Hamlet’s soliloquy perhaps suggests, be a morality, a conscience, that had a different relation to the unknown. The coward, after all, always thinks he knows what he fears, and knows that he doesn’t have the wherewithal to deal with it. The coward, like Freud’s super-ego, is too knowing. A coward – or rather, the cowardly part of ourselves – is like a person who must not have a new experience.”

(…)

“But that other aspect of the super-ego, the censor or judge, Freud believes, is just an internalised version of the prohibiting father, the father who says to the Oedipal child: ‘Do as I say, not as I do.’ The super-ego, by definition, despite Freud’s telling qualifications, under-interprets the individual’s experience. It is, in this sense, moralistic rather than moral. Like a malign parent it harms in the guise of protecting; it exploits in the guise of providing good guidance. In the name of health and safety it creates a life of terror and self-estrangement. There is a great difference between not doing something out of fear of punishment, and not doing something because one believes it is wrong. Guilt isn’t necessarily a good clue as to what one values; it is only a good clue about what (or whom) one fears. Not doing something because one will feel guilty if one does it is not necessarily a good reason not to do it. Morality born of intimidation is immoral. Psychoanalysis was Freud’s attempt to say something new about the police.

We can see the ways in which Freud is getting the super-ego to do too much work for him: it is a censor, a judge, a dominating and frustrating father, and it carries a blueprint of the kind of person the child should be. And this reveals the difficulty of what Freud is trying to come to terms with: the difficulty of going on with the cultural conversation about how we describe so-called inner authority, or individual morality. But in each of these multiple functions the ego seems paltry, merely the slave, the doll, the ventriloquist’s dummy, the object of the super-ego’s prescriptions – its thing. And the id, the biological forces that drive the individual, are also supposed to be, as far as possible, the victims, the objects of the super-ego’s censorship and judgment. The sheer scale of the forbidden in this system is obscene. And yet, in this vision of things, all this punitive forbidding becomes, paradoxically, one of our primary unforbidden pleasures. We are, by definition, forbidden to find all this forbidding forbidden. Indeed we find ways of getting pleasure from our restrictedness.”

(…)

“What does the Freudian super-ego look like if you take away its endemic cruelty, its unrelenting sadism? It looks like Sancho Panza. And like Sancho Panza, the absurd and obscene super-ego is a character we mustn’t take too seriously.

‘Sancho proves to have too much mother wit to be considered a perfect fool,’ Nabokov writes, ‘although he may be the perfect bore.’ We certainly need to think of our super-ego as a perfect bore, and as all too gullible in its apparent plausibility. We need, in other words, to realise that we may be looking at ourselves a little more from Sancho Panza’s point of view, whether or not we are rather more like Don Quixote than we would wish.”

Read the article here

The super-ego as the prohibiting father and the father, as Phillips puts it, harms in the guise of protecting; exploits in the guise of providing good guidance. In the name of health and safety he creates a life of terror and self-estrangement.

We should take this criticism of the super-ego very seriously. Many contemporary problems in society can be better understood and explained if we realize that there is something utterly perverse in our self-criticism, in our super-ego. It’s only because we are so used to being exploited in the guise of providing good guidance, we do it to ourselves on a daily basis, that we hardly notice it when religious leaders, politicians and civil servants do the same thing.

Your conscience isn’t telling you how to distinguish good from evil, first and foremost your conscience wants revenge, your conscience wants to torture you.