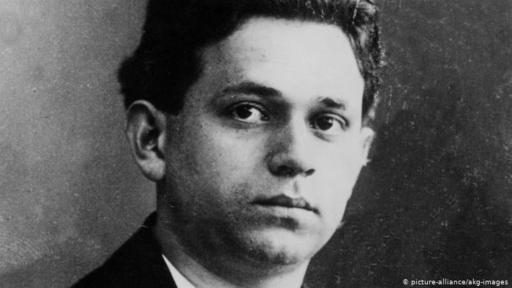

Time for Tucholsky - here's Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim in NYT:

'With hindsight, some critics wondered if his sendups of Nazi bigwigs and fascist foot soldiers hadn’t been a little too funny, like the poem “Joebbels,” which in thick Berlin dialect deflates the Führer’s diminutive propaganda minister, or a spoof Hitler Youth essay weighing who was the greater German, Goethe or Hitler. Maybe such antics helped make the Nazis look harmless. In any case readers laughed. And Hitler still won.

By then Tucholsky had already chosen a life in exile, first in Paris, then in Sweden. Bitterly aware of his own impotence, he stopped writing and fell into depression.

But in 1931, two years before members of the Hitler Youth hurled his books onto a bonfire, and four years before overdosing on sleeping pills, Tucholsky wrote a love story as light as a summer breeze. Not much happens in CASTLE GRIPSHOLM, which New York Review Books has just reissued in a sympathetic translation by Michael Hofmann, though there is enough witty banter, fresh air and sex to propel the story along. The lingering power of this deceptively slight novel comes from the shiver of foreboding that courses through it.

A writer (named Tucholsky) and his girlfriend, Lydia, both hard-bitten city dwellers, vacation in the Swedish countryside. Nothing mars their idyll — not even pompous fellow tourists and overpriced booze — until they discover a girl who is being tyrannized in a nearby boarding school. Reluctant at first, they soon find that they cannot turn their backs on her suffering. But will they be able to make much of a difference?

By the time Tucholsky wrote “Castle Gripsholm” in Sweden, that question had become painfully personal. Born into a prosperous Jewish family in Berlin, he quickly showed talent as a polemicist. (While still in school he published a mock fairy tale poking fun at Kaiser Wilhelm’s taste in art.)

Tucholsky studied law and served on the Eastern Front in World War I, an experience that forged his lifelong pacifism. Though the targets of his satire included the class bias of the Weimar legal system, puffed-up writing and the vacuity of popular music, most of his efforts were directed at the boorishness of the nascent Third Reich.

“A satirist,” Tucholsky once wrote, “is an offended idealist.”'

(...)

'According to one Jewish proverb, a man who saves one life saves the whole world. Tucholsky was too much of a realist to subscribe to that view. Yet he let nobody off the hook.

Consider this passage about the “quiet, thoughtful” craftsmen who built the boarding school that harbors so much suffering: “When it was finished, they plastered the walls, and some of the rooms were painted, many more were papered, all differently, and according to their instructions. Then they had gone away phlegmatically. The house was finished; it didn’t matter what happened in it now. That wasn’t their affair, they were only the builders. The courtroom where people are tortured was, to begin with, a rectangle of brick walls, smooth and whitewashed. A painter had stood on his ladder and whistled cheerfully as he painted a gray stripe right round the room, as he had been told to; as far as he was concerned, it was a piece of craftsmanship.”

Tucholsky’s verdict on his own ability to change things with his pen was devastating. In 1923 he wrote, “I have success, but no impact whatsoever.”

But outside politics his impact on his contemporaries was profound. Some of his quips remain in circulation to this day. His mix of snark and forensic social observation defined a certain brand of cool for the interwar generation. And, long before Lydia, he defined as a feminine ideal a woman who was outwardly capricious and ditsy, yet levelheaded, warm and fiercely independent.

The prototype was Claire, the protagonist of the illustrated novella “Rheinsberg,” which Tucholsky published in 1912 when he was barely 22. It prefigures “Castle Gripsholm,” featuring a young couple vacationing in the countryside where they bicker in a patois of their own devising, make love and poke fun at bourgeois mores. The book was a runaway success. For a while, Tucholsky and the book’s illustrator ran a pop-up store in Berlin where customers were served a shot of schnapps with each purchase. German couples adopted Claire’s droll mix of colloquial dialect and hapless High German, as their private language.

In both “Rheinsberg” and “Castle Gripsholm” Tucholsky uses patois to heighten the daffy sex appeal of his female characters. In “Castle Gripsholm,” it is Lydia’s use of Missingsch, a customizable blend of High German and the earthy Platt dialect of northern Germany, that reveals her no-nonsense character. As the narrator describes Missingsch, “it slithers about on the carefully wax-polished stairs of German grammar, before falling flat on its face in its beloved Platt.” In this translation, Hofmann forgoes any attempt at finding an English equivalent. In his introduction he writes that trying to render Missingsch using a “‘corresponding’ dialect” in English would be “distracting, paradoxical, absurd.” He cites Tucholsky’s own disdain for a German translation of “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” that had Mellors speaking in a “‘Bavarian mountain dialect.’”'

Read the article here.

To not translate dialect is probably the best solution, to start with that.

If the satirist is an offended idealist and the cynic is a disappointed idealist, then most humans should become satirists. It's impossible to remain an idealist for more than two years without being offended. And two years is already a long time.

Resistance is not always idealism. I would say that the most effective resistance is a mixture of historical knowledge, a tiny drop of civilization (and God knows I'm skeptical about civilization) and deep distrust of the masses and their sentiments, their fears, their festivities, their tears, and above all their hatred. (I'm not necessarily better than the masses, but I'm quite sure that the masses rarely bring out the best in the individual).

How you can believe in democracy and distrust the masses is a good question.

I don't believe in democracy, I accept it, I'm willing to defend it, the messiness of it is preferable to the neatness and cleanliness that dictators, would-be-dictators and their supporters strive for.