On Levinas - Robert Zaretsky in NYT:

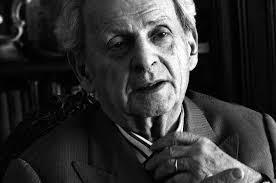

‘Twenty-five years ago, the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas died in Paris. Born in Lithuania and naturalized in France, Levinas had led weekly Torah readings until shortly before his death just shy of his 90th birthday. I often thought about his age this spring as I worked as a volunteer in a nursing home. Not only was Levinas as old as several of the residents who I helped to feed, but he was engaged in an activity — being with others — denied to the residents since the pandemic burst into their lives. In both his person and his principles, Levinas offers a guide for the crises that now threaten nursing homes.

“Le visage,” or the face, happens to be the very grounding for the ethics proposed by Levinas. Indeed, what he understands by the words “face” and “ethics” have little to do with their common usage. For Levinas, the face is not the sum total of physical pieces — nose, eyes, ears, mouth, etc. — that we present to the world. Instead, the face, as Levinas frames it, marks what is utterly otherthan those specific physical features. As he declared in his book “Totality and Infinity,” the face is the naked and living presence of the Other.’

(…)

‘A group of Russians, survivors of the German siege of Stalingrad, watch with mounting anger as a line of captured German soldiers carry dead bodies out of a building’s basement. Staring at a broken officer cradling the limp body of a young girl in his arms, an enraged woman steps from the crowd and approaches the German with a brick clutched in her hand. Rather than hitting the officer, she suddenly plunges her hand into her pocket, pulls out a lump of bread, gives it to the officer and quickly walks away.

This scene, taken from Vasily Grossman’s novel “Life and Fate,” was often cited by Levinas as an example of how the face upends our habitual state of being. At that “extraordinary” moment, Levinas suggests, the woman faced someone who was no longer a German officer — here again, the sensible is stripped away — and is revealed as Other: a face that constitutes all the ethics we need by “revealing the vulnerability of the outsider and our common humanity.” She stuns him with the bread rather than the brick not because of who she is, but because of who he is.

Crucially, this ethical stance, unlike Christian or Kantian ethics, reflects an asymmetrical relationship. We must care for others not because we are all equal, but because we are not at all equal. It is not a case of “He’s not heavy, he’s my brother,” than “He is heavy because he is more than my brother.” We move from the Cartesian “I think, therefore I am,” to the Levinasian “You are, therefore I am.” When faced by the Other, Levinas concludes, “I am infinitely responsible.”’

Read the article here.

When I read about Levinas, sometimes also when I read Levinas I can’t escape a feeling of mild annoyance.

I can understand why Levinas would insist that i have infinite responsibility towards the Other, at least I think I can understand why he insists on that kind of responsibility.

But I also feel that I can be barely responsible for myself and that the risk is quite real that infinite responsibility for the Other will belittle the Other, take away his liberties. Everything is easy to misunderstand, but the idea of infinite responsibility can easily be abused or twisted into something utterly unpleasant.

And is it out of infinite responsibility that this young woman decided to give the soldier a piece of bread? Do we do her injustice when we call this act kindness?

What is the difference between kindness and infinite responsibility? Do we need to burden ourselves with these two words? What does it add to the Kantian ethics, except the language, the slight echo and the seduction of the New Testament?

Eternal love and infinite responsibility?

In this world small attempts at kindness are enough for me. Usually I prefer the understatement.