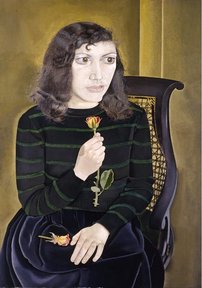

And now something about a funny phone book - Frances Wilson in TLS on Lucian Freud and his biographer William Feaver:

‘The lives of Lucian Freud does not read like a novel, but nor does it read like a traditional biography. Feaver seems unaware of the genre’s obligation to be dull, or prurient, or both, or the biographer’s obligation to draw a moral lesson from his subject’s life. In the 1970s, when the idea of a brief account of the artist was first seeded, Freud referred to the project as “the first funny art book”, but Feaver’s art book, like Freud’s fame, had swollen with the century. What was emerging instead might be called the first funny phone book, and not only because of the manuscript’s bulk. Crafted around daily telephone interviews, a more appropriate title might have been, in homage to the genre known as “table talk”, The Telephone Talk of Lucian Freud. “Hello, Villiam”, Freud would say, regardless of whether it was the crack of dawn or the deep of night. “How goes it? How old am I now?”’

(…)

‘But what about the many other people Freud has “been with who haven’t been painted”? The problem with those people – Feaver included – who have not also become portraits is that he was “not”, as Freud puts it, “conscious of the rhythm of getting caught up with them”. It is a striking description of the relationship between artist and sitter, and the biographer and his subject get caught up in a rhythm of their own. Feaver, who is happy to sit for Frank Auerbach, “demurred” when Freud suggested that he sit for him as well, an arrangement that would, as Freud knew, muddy the waters around who in their relationship was the artist, and who the model. Demanding from his own sitters punishing levels of commitment and self-exposure (he expected David Hockney to sit for 100 hours, and spent 4,000 hours on painting his mother), Freud played cat and mouse when it came to sitting for Feaver.’

(…)

‘Feaver takes us to the scene of their first encounter: “Lunchtime. He changed out of his chef’s trousers behind a chair and emerged in a green cord suit. We left Maida Vale in the Bentley at violent speed and talk turned to Chardin without any appreciable effect on his driving … Outside L’Etoile in Charlotte Street he parked unhesitatingly on a double yellow line and sidled into the restaurant.” Returning to the Bentley after lunch, Freud threw away the parking tickets tucked under the wipers, headed at top speed to a street corner, picked up a waiting girl, took her to a bank where she went inside and emerged with a plastic bag bulging with notes. “Why?” queried Feaver. “Oh, I’m going bankrupt.” Apart from the telephone, the Bentley, and watching sport on television, Freud might be living in the eighteenth century. His studio is a world of pugilism, personality and roughhouse. He loves, drinks and gambles like a frockcoated libertine; he roasts woodcock – or partridge, parsnips and parsley – for breakfast, paints race horses and whippets, frolics with pimps and aristos and enjoys the droit de seigneur: “nothing to do with me that they’re having children”, he said of his women. He sees his friends as Rowlandson cartoons: Andrew Parker Bowles is “staunch, downright and potentially good in a scrap”, Kate Moss is “slightly gangster’s moll”. We expect him to run into Isaac Cruikshank at the ale house, or spend the weekend shooting with Charles James Fox.’

(…)

‘He is aware, however, of the rhythm of psycho–analysis in Freud’s world. His Holland Park studio is a riff on Berggasse 19, the Viennese address where his grandfather saw his own clients; Lucian, like Sigmund, insists on regularity and punctuality and does not let his visitors meet. Feaver wonders if Freud’s first portrait of a male nude, “Naked Man with Rat” (1977–8), is related to Sigmund Freud’s Ratman case study, published as “Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis” (1907). “It could be, but isn’t”, says Lucian. “I wasn’t even aware of it.” (This pose is in keeping with his insistence that “I have the opposite of an interest in anything to do with my family”.) “Naked Man with Rat” was painted to pay off a loan that the sitter, Raymond Hall (who went by the name Raymonde and is otherwise called Raymond Jones), had made to Freud in order to cover a gambling debt. Raymond lies on the sofa, his hand, next to his lolling penis, clasping the rat. In his diary, Freud sketched this same penis dangling above a whiskery rat subdued with champagne and sleeping pills. Ripping out the page, he inscribed it, in his childish scrawl, to “Raymond, Rat Man, love LUCIAN”.”

(…)

‘Feaver does not press the relation between the two rat men, but his hunch is surely right. Ernst Lanzer, Sigmund Freud’s Rat Man, was the son of a gambler (the German for which is “Spielratte”, or “rat play”). Lanzer had an obsessive fear of, and fascination with, debt and was tormented by the idea that if he did not pay back in person the 3.80 kronen he owed to a lieutenant in his division, a rat would be inserted into his father’s anus. His attempts to return the money – what Freud called his “rat currency” – take on farcical levels of complexity. Lucian Freud’s own relationship with money – he was “liberated” and “stimulated” by debt – was similarly complex, and we get the impression that his paintings are the currency that allows him to gamble. “If I hadn’t been so in debt”, he said on winning a million at the races after a tip from Parker Bowles, “I wouldn’t have bet so much”. Addicted to risk, his art was a version of Russian roulette while the game of returns was played by all the Freud family. Lucian tells a story about running into his cousin, Walter, on the bus. “‘Why don’t we meet’, says Walter. ‘After we meet, what would we do’, replies Lucian. ‘You could borrow small sums of money from me and then I could try and get some back’. I think he was serious.”’

(…)

‘Feaver’s refusal to provide a psychopathology of Freud’s everyday life – the artist’s need to push every situation to its extreme, his refusal to let something go before it becomes “disconcerting” – means that a charge is kept below the surface of his narrative, much as the unspoken relation between Freud and his sitters charges his portraits.

Freud’s last years, the most finely wrought section of this magnificent book, read like the last days of Pompeii. When his brain begins to fade, he asks Feaver not “how old am I now”, but “Who am I?” He wants, he says, to paint himself to death, but it is his brother, Clement, who dies first: “We never got on”, says Lucian. “He’s dead now. Always was, actually.”’

Read the review here.

Artist and sitter, biographer and his subject, there are many similarities indeed. One can ask: what does the sitter get out of this deal? Some money, but not too much, the sensation of being observed, sometimes the sensation of being observed by somebody famous.

However the relationship between biographer and subject is often more equal. Even when the biographer is mediocre, to be written about is most often better than to be not written about.

Above all, Lucian Freud’s work and life remind us that art is made beyond good and evil. The moment art becomes an excuse for (most often obvious) moral lessons we enter the world of religious art and religious art without mythology is boring.

Also, I understand the addiction to risks but the problem with all addictions is that they become dull. Even risk taking can become repetitive.

But the addiction to playing it safe – roughly, the secular the religion of the bourgeois – sooner or later feels like the denial of life, which of course is also a way of conquering death.