On saving Nietzsche – Hugo Drochon in TLS:

‘In the English-speaking world Bertrand Russell declared the Second World War to be “Nietzsche’s war”. Safely ensconced in the US, at Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, Russell was busy writing his A History of Western Philosophy, in which he took a disparaging – and later much criticized – view of Nietzsche. Russell considered his History to be his personal response to the war, and that is also how Kaufmann understood his book, as a personal “cultural-political act”, as Stanley Corngold, in his brilliantly erudite and playful intellectual biography of Kaufmann, shows so well.

Instead of representing him as the philosopher of the Third Reich, Kaufmann placed Nietzsche firmly in the “grand” Western philosophical tradition that included “Socrates and Plato, Luther and Rousseau, Kant and Hegel”. He also registered Nietzsche’s debt to Goethe, and on the personal level it is this Goethean line, especially in how it relates to the German educational ideal of Bildung, that was to prove decisive. Every reader of Nietzsche is confronted with the fact that Nietzsche appears to write directly for you. It is that quality of his writings that makes it so intoxicating for those with the palate for it, and Kaufmann seemed to have taken to it like strong wine. Nietzsche became Kaufmann’s educator.’

(…)

‘That attempt – to turn Nietzsche into a respectable philosopher – was, as we now know, entirely successful, with Nietzsche taking his deserved place in the canon of Western philosophy taught throughout universities across the globe. But it came at a cost: the price paid to save Nietzsche from the philosophical abyss was to deny him any interest in politics. As Kaufmann writes in his epilogue: “we have tried to show that Nietzsche opposed both the idolatry of the State and political liberalism because he was basically ‘antipolitical’ and, moreover, loathed the very idea of belonging to any ‘party’ whatever”. In line with his view of Nietzsche as educator, Kaufmann interpreted Nietzsche’s politics as essentially a Geistekrieg, an “intellectual war” of personal self-mastery and the “sublimation” of the instincts.

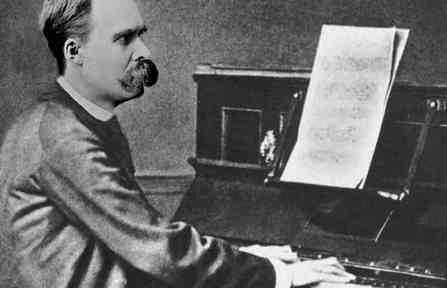

If Nietzsche is part of polite conversation in the English-speaking world today, it is thanks to one man: Walter Kaufmann. A German-Jewish émigré who arrived in the US in 1939, after graduating from Williams College he interrupted his doctoral studies at Harvard to enlist in the US Army Air Force and served as an interrogator for Military Intelligence during the war. In Berlin he chanced upon an edition of Nietzsche’s collected works and was immediately – like so many before and after him – captivated. Having discharged his duty, he returned to Harvard resolved to write his PhD on Nietzsche. Within a year he had completed his dissertation on “Nietzsche’s Theory of Values” and started teaching philosophy at Princeton University, which he would continue to do for the next thirty-three years. Three years later, in 1950, before he even turned 30, he published his first book: Nietzsche: Philosopher, psychologist, antichrist. We would never read Nietzsche the same way again.

It is hard to overestimate the challenges the young Kaufmann faced. The Nazis made a conscious attempt to enlist Nietzsche as one of their intellectual forefathers: Alfred Baeumler, head of the Institute for Political Pedagogy in Berlin, wrote a book in 1931 titled Nietzsche, der Philosoph und Politiker, in which he tried to link Nietzsche’s theory of the state with Nazi state theory. On reading the book, Thomas Mann declared it a “Hitler prophecy”.

In fact the collection of Nietzsche’s works Kaufmann picked up in Berlin was the Musarion edition, compiled by the Nazi brothers Richard and Max Oehler (younger cousins of Nietzsche himself) and the propagandist Friedrich Würzbach. Despite later being thrown out by the Nazi regime for being “half-Jewish”, Würzbach was one of the loudest proponents of the “biological-racial” reading of Nietzsche. Together with Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the Oehler brothers founded the Nietzsche-Archiv in Weimar, and subsequently turned it into a Nazi propaganda machine: Hitler was a regular visitor in the 1930s. They helped propagate the view that Nietzsche was planning a magnum opus at the end of his life entitled The Will to Power, using a fraudulent collection of late notes Nietzsche’s sister had put together. In the 1926 afterword to the Musarion edition, Würzbach directly linked Nietzsche’s ideas to Nazi race theories. It was towards these figures that Kaufmann directed much of his ire.

In the English-speaking world Bertrand Russell declared the Second World War to be “Nietzsche’s war”. Safely ensconced in the US, at Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, Russell was busy writing his A History of Western Philosophy, in which he took a disparaging – and later much criticized – view of Nietzsche. Russell considered his History to be his personal response to the war, and that is also how Kaufmann understood his book, as a personal “cultural-political act”, as Stanley Corngold, in his brilliantly erudite and playful intellectual biography of Kaufmann, shows so well.

Instead of representing him as the philosopher of the Third Reich, Kaufmann placed Nietzsche firmly in the “grand” Western philosophical tradition that included “Socrates and Plato, Luther and Rousseau, Kant and Hegel”. He also registered Nietzsche’s debt to Goethe, and on the personal level it is this Goethean line, especially in how it relates to the German educational ideal of Bildung, that was to prove decisive. Every reader of Nietzsche is confronted with the fact that Nietzsche appears to write directly for you. It is that quality of his writings that makes it so intoxicating for those with the palate for it, and Kaufmann seemed to have taken to it like strong wine. Nietzsche became Kaufmann’s educator.

There are parallels between Nietzsche’s life and Kaufmann’s: the precocious student, the university appointment at a young age, the war experience, the chance encounter with a philosopher, the emigration, the loneliness, the poetry, the untimely death. Kaufmann died in 1980 at the age of fifty-nine, only four years older than Nietzsche was when he died. According to his brother Felix, Walter died from having swallowed a parasite on his fourth Faustian journey of self-discovery through West Africa, which attacked his heart. He died later of a burst aorta in his Princeton home.

One point of disagreement, however, was religion. While Nietzsche’s “death of God” is still one of his most famous pronouncements, in 1961 Kaufmann wrote Faith of a Heretic. Born in Freiburg in 1921, Kaufmann was raised a Lutheran, but realizing he didn’t understand the Holy Ghost and that all his grandparents were Jewish (his father had converted, but not his mother), he abjured Christianity and set off to study under the Reform Rabbi Leo Baeck at the Berlin Institute for Judaic Studies in 1938. Those studies were cut short by emigration, but the interest in religion would continue, and the disagreement with Nietzsche was signalled by the third element of the subtitle of his Nietzsche book: antichrist. The second element – psychologist – refers to Nietzsche’s educative function. For an argumentative Jewish émigré with an accent and boyish looks, in what was still a predominantly antisemitic academic culture, a degree of self-awareness seemed crucial. Philosopher, the first part of the subtitle, was the stated aim of the book.

That attempt – to turn Nietzsche into a respectable philosopher – was, as we now know, entirely successful, with Nietzsche taking his deserved place in the canon of Western philosophy taught throughout universities across the globe. But it came at a cost: the price paid to save Nietzsche from the philosophical abyss was to deny him any interest in politics. As Kaufmann writes in his epilogue: “we have tried to show that Nietzsche opposed both the idolatry of the State and political liberalism because he was basically ‘antipolitical’ and, moreover, loathed the very idea of belonging to any ‘party’ whatever”. In line with his view of Nietzsche as educator, Kaufmann interpreted Nietzsche’s politics as essentially a Geistekrieg, an “intellectual war” of personal self-mastery and the “sublimation” of the instincts.

That view did not go unchallenged. In 1970 the Irish diplomat and Burke scholar Conor Cruise O’Brien wrote a piece entitled “The Gentle Nietzscheans”, where he lambasted Kaufmann for having sanitized Nietzsche from his more explicitly cruel pronouncements, declaring him to be an anti-Christian antisemite, and that his politics amounted to pure Machiavellianism. But as Corngold correctly points out in his excellent postscript, in which he surveys some of the main strands of criticism that Kaufmann’s Nietzsche has been subjected to, Kaufmann had not ducked the challenge of the “tough” Nietzscheans, but rather faced it head-on. In the same passage from the epilogue he rejected the “tough Nietzscheans” who see him as the prophet of great wars and power politics and an opponent of political liberalism and democracy, while at the same time criticizing the “tender Nietzscheans” for believing that Nietzsche was therefore a liberal, democrat or socialist. Corngold also shows that the passages O’Brien relied on came mostly from the discredited The Will to Power. But perhaps what is most noteworthy about O’Brien’s piece is that it was published in the New York Review of Books, the epitome of polite conversation.’

(…)

‘We are eternally indebted to Kaufmann for having saved Nietzsche from the Nazis, and his legacy is that today, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, we can now leave those twentieth-century debates behind. Paradoxically, perhaps the best way to move forward with Nietzsche is to return him to his own time: late nineteenth-century Europe.’

Read the review here.

Nietzsche, besides his style (‘Every reader of Nietzsche is confronted with the fact that Nietzsche appears to write directly for you. It is that quality of his writings that makes it so intoxicating for those with the palate for it’) offers something for many. Anti-Semitism? You can find it. Filo-Semitism? You can find it also. Machiavellianism? You will be able to find your citations.

I found it more difficult to think of Nietzsche as a socialist, a democrat or a liberal.

He showed us the weak spots and rottenness in our enlightened and seemingly self-evident way of thinking.