On burning the evidence – Jill Lepore in The New Yorker:

‘Donald Trump is not much of a note-taker, and he does not like his staff to take notes. He has a habit of tearing up documents at the close of meetings. (Records analysts, armed with Scotch Tape, have tried to put the pieces back together.) No real record exists for five meetings Trump had with Vladimir Putin during the first two years of his Presidency. Members of his staff have routinely used apps that automatically erase text messages, and Trump often deletes his own tweets, notwithstanding a warning from the National Archives and Records Administration that doing so contravenes the Presidential Records Act.’

(…)

‘Those N.D.A.s haven’t stopped a small village’s worth of ex-Trump Cabinet members and staffers from blabbing about him, much to the President’s dismay. “When people are chosen by a man to go into government at high levels and then they leave government and they write a book about a man and say a lot of things that were really guarded and personal, I don’t like that,” he told the Washington Post. In 2019, he tweeted, “I am currently suing various people for violating their confidentiality agreements.” Last year, a former campaign worker filed a class-action lawsuit that, if successful, would render void all campaign N.D.A.s. Trump has only stepped up the fight. Earlier suits were filed by Trump personally, or by his campaign, but, last month, the Department of Justice filed suit against Stephanie Winston Wolkoff for publishing a book, “Melania and Me,” about her time volunteering for the First Lady, arguing, astonishingly, that Wolkoff’s N.D.A. is “a contract with the United States and therefore enforceable by the United States.” (Unlike the suit against Trump’s former national-security adviser John Bolton, relating to the publication of his book, “The Room Where It Happened,” there is no claim that anything in Wolkoff’s book is or was ever classified.) And Trump hasn’t stopped: last year, he required doctors and staff who treated him at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to sign N.D.A.s.’

(…)

‘The Trump Presidency nearly destroyed the United States. Will what went on in the darker corners of his White House ever be known?’

(…)

‘Governments that commit atrocities against their own citizens regularly destroy their own archives. After the end of apartheid, South Africa’s new government organized a Truth and Reconciliation Commission because, as its report stated, “the former government deliberately and systematically destroyed a huge body of state records and documentation in an attempt to remove incriminating evidence and thereby sanitise the history of oppressive rule.” Unfortunately, the records of the commission have fared little better: the archive was restricted and shipped to the National Archives in Pretoria, where it remains to this day, largely uncatalogued and unprocessed; for ordinary South Africans, it’s almost entirely unusable. In the aftermath of the Trump Administration, the most elusive records won’t be those in the White House. If they exist, they’ll be far away, in and around detention centers, and will involve the least powerful: the families separated at the border, whose suffering federal officials inflicted, and proved so brutally indifferent to that they have lost track of what children belong to which parents, and how to find them.

In 1950, Truman signed the Federal Records Act, which required federal agencies to preserve their records. It did not require Presidents to save their papers, which remained, as ever, their personal property. In 1955, Congress passed the Presidential Libraries Act, encouraging Presidents to deposit their papers in privately erected institutions—something that every President has done since F.D.R., who was also the first President to install a tape recorder in the White House, a method of record-keeping that was used by every President down to Richard M. Nixon.’

(…)

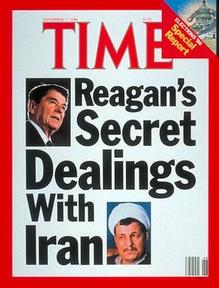

‘Reagan’s was the first Administration to use e-mail. Preparing to leave the White House, people in the Administration tried to erase the computer tapes that stored its electronic mail. The correspondence in question included records of the Iran-Contra arms deal, which was, at the time, under criminal investigation. On the last day of Reagan’s Presidency, the journalist Scott Armstrong (formerly of the Washington Post), along with the American Historical Association, the National Security Archive (a nonprofit that Armstrong founded, in 1985), and other organizations, sued Reagan, George H. W. Bush, the National Security Council, and the archivist of the United States. That lawsuit remained unresolved four years later, in 1992, when C. Boyden Gray, a lawyer for the departing President, George H. W. Bush, advised him that destroying things like telephone logs was not a violation of the Presidential Records Act, because, he asserted, the act does not cover “ ‘non-record’ materials like scratch pads, unimportant notes to one’s secretary, phone and visitor logs or informal notes (of meetings, etc.) used only by the staff member.”’

(…)

‘Early in George W. Bush’s first term, his Administration disabled the automated e-mail archive system. Nearly all senior officials in the Bush White House used a private e-mail server run by the Republican National Committee. Then, between 2003 and 2009, they claimed to have lost, and later found, some twenty-two million e-mail messages. Nor has this practice been limited to the White House. Hillary Clinton’s use of a personal e-mail account on a private e-mail server to conduct official correspondence while serving as Obama’s Secretary of State violated the Federal Records Act, which allows the use of a personal account only so long as all e-mails are archived with the relevant agency or department; Clinton’s were not. “The American people are sick and tired of hearing about your damn e-mails,” Bernie Sanders said to Clinton in 2015, during a primary debate, all Larry David-like. But, closer to Election Day, renewed attention on Clinton’s e-mails diminished her chances of defeating Trump.’

(…)

‘The archivist of the United States, David Ferriero, has copies of three letters that he wrote, as a kid in the nineteen-sixties, framed on his office wall. One is to Eisenhower, asking for a photograph. The second is to John F. Kennedy, inquiring about the Peace Corps. The third is to Johnson: “Mr. President, I wish to congratulate you and our country for passing John F. Kennedy’s Civil Rights Bill.” The originals of those letters ended up in the National Archives, preserved, long before the passage of the Presidential Records Act.

Ferriero, an Obama appointee, says that the P.R.A. operates, essentially, as an honor system. He wishes that it had teeth. Instead, it’s all gums. Kel McClanahan, a national-security lawyer, told me, “If the President wanted to, he could pull together all of the pieces of paper that he has in his office and have a bonfire with them. He doesn’t view the archivist as an impediment to anything, because the archivist is not an impediment to anything.”

After Trump’s Inauguration, in January, 2017, the National Archives and Records Administration conferred with the White House to establish rules for record-keeping, and, given the novelty of Trump’s favored form of communication, advised Trump to save all his tweets, including deleted ones. Trump hasn’t stopped deleting his tweets; instead, the White House set up a system to capture them, before they vanish. On February 22nd, the White House counsel Don McGahn sent a memo on the subject of Presidential Records Act Obligations to everyone working in the Executive Office of the President, with detailed instructions about how to save and synch e-mail. McGahn’s memo also included instructions about texting apps:

You should not use instant messaging systems, social networks, or other internet-based means of electronic communication to conduct official business without the approval of the Office of the White House Counsel. If you ever generate or receive Presidential records on such platforms, you must preserve them by sending them to your EOP email account via a screenshot or other means. After preserving the communications, you must delete them from the non-EOP platform

It appears that plenty of people in the White House ignored McGahn’s memo. Ivanka Trump used a personal e-mail for official communications. Jared Kushner used WhatsApp to communicate with the Saudi crown prince. The press secretary Sean Spicer held a meeting to warn staff not to use encrypted texting apps, though his chief concern appears to have been that White House personnel were using these apps to leak information to the press.’

(…)

‘It’s not impossible that his White House will destroy records not so much to cover its own tracks but to sabotage the Biden Administration. This would be a crime, of course, but Trump could issue blanket pardons. Yet, as with any Administration, there’s a limit to what can be lost. Probably not much is on paper, and it’s harder to destroy electronic records than most people think. Chances are, a lot of documents that people in the White House might wish did not exist can’t really be purged, because they’ve already been duplicated. Some will have been copied by other offices, as a matter of routine. And some will have been deliberately captured. “I can imagine that at State, Treasury, D.O.D., the career people have been quietly copying important stuff all the way along, precisely with this in mind,” the historian Fredrik Logevall, the author of a new biography of Kennedy, told me.

Other attempts to preserve the record appear to have been less successful. The White House’s P.R.A. guidelines, as worked out with the National Archives, forbade the use of smartphone apps that can automatically erase or encrypt text messages. It’s possible that the White House has complied with those guidelines, but there’s nothing that the National Archives could have done, or could do now, if it hasn’t. Watchdog groups sued, concerned about the use of such apps, but the Justice Department successfully argued that “courts cannot review the president’s compliance with the Presidential Records Act.” In 2019, the National Security Archive joined with two other organizations in a suit against Trump that led to a court’s ordering the Administration to preserve not only “all records reflecting Defendants’ meetings, phone calls, and other communications with foreign leaders” but records having to do with the Administration’s record-keeping practices. Earlier this year, the judge in that case dismissed the lawsuit: “The Court is bound by Circuit precedent to find that it lacks authority to oversee the President’s day-to-day compliance with the statutory provisions involved in this case.”’

(…)

‘The memo that Don McGahn sent to executive-office personnel in February, 2017, came with a warning, about leaving the White House:

At all times, please keep in mind that presidential records are the property of the United States. You may not dispose of presidential records. When you leave EOP employment, you may not take any presidential records with you. You also may not take copies of any presidential records without prior authorization from the Counsel’s office. The willful destruction or concealment of federal records is a federal crime punishable by fines and imprisonment.

Custody of the records of the Trump White House will be formally transferred to the National Archives at noon on January 20, 2021, the minute that Biden takes his oath of office on the steps of the Capitol. Trump, defying tradition, is unlikely to attend that ceremony. It’s difficult, even, to picture him there. Maybe he’ll be in the Oval Office, yanking at the drawers of Resolute, the Presidential desk, barking out orders, cornered, frantic, panicked. Maybe he’ll tweet the whole thing. The obligation, the sober duty, to save the record of this Administration will fall to the people who work under him. It may well require many small acts of defiance.

The truth will not come from the ex-President. Out of a job and burdened by debt, he’ll want to make money, billions. He’ll need, crave, hunger to be seen, looked at, followed, loved, hated; he’ll take anything but being ignored. He may launch a TV show, or even a media empire. Will he sell secrets to American adversaries, in the guise of advice and expertise? It isn’t impossible.’

Read the complete article here.

Most presidents had reasons – understandably, being a president is a dirty job – to destroy some evidence of his time as Commander in Chief.

Some presidents more than others, Reagan, Iran-Contra scandal, to name just one.

The most hilarious sentence in this essay was the possibility that Trump would become a spy for hire. Nothing is impossible.

Snowden got his Russian Passport, maybe in four years or so, Trump will have a Russian passport as well.