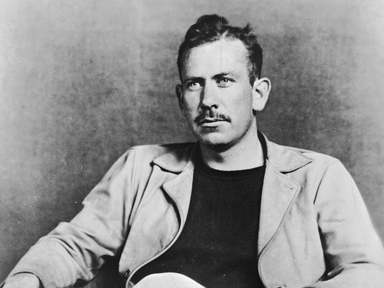

On greatness and its surroundings – Phillip Lopate in TLS:

‘No one can deny Steinbeck’s energy, power and productivity, but some of his works, like The Red Pony and Of Mice and Men, have become high school curricular staples, gateway introductions to the complexities of literature. His most enduring work, The Grapes of Wrath, is probably taught more at the secondary school level in the United States than in universities. While his brand and image may linger more today through prestigious Hollywood adaptations or screenplays, like John Ford’s Grapes of Wrath, or Elia Kazan’s East of Eden and Viva Zapata!, Steinbeck’s reputation seems stuck a few notches below greatness.

His latest biographer, William Souder, would kick him upstairs. But to do so he first has to acknowledge Steinbeck’s pirouettes in and out of fashion.’

(…)

‘ In its citation, in 1962, the Nobel committee (with its customary preference for progressive values) praised Steinbeck’s feeling for “the oppressed, the misfits and the distressed”. He was also lauded for his “empathy”, though it seemed to extend mainly to the poor. “John would say that the one thing he could not bear was another human being oppressed, abused or taken advantage of by anyone more powerful, especially if the motive was greed”, Souder writes. The crux of his claim for Steinbeck’s niche in the pantheon is that he was America’s great social realist (a style, note, no longer in fashion). He took on the injustices of capitalist society and the ruling classes’ use of the police to keep down the masses. It’s rather like the current revision of Jack London as not just a writer of boys’ books but a radical thinker. London, however, had a wild streak of genius that Steinbeck lacked.’

(…)

‘ In any case, hanging out with this frowning, solemn, humourless, egotistical, insecure man for over 400 pages is not the most enjoyable experience. He detested appearing in public: “Nothing made him angrier than the expectation that he was obligated to perform for his admirers”. Steinbeck seems charmless here – or if he did have charm, it’s not rendered in this biography.

What we get is a crisp foray through the main events, with emphasis on juicy vignettes about quarrels and love affairs. This is not the definitive Steinbeck biography: that honour belongs to Jackson Benson’s True Adventures of John Steinbeck (1984), generously credited here. But Souder has hunted in the archives, interviewed those still alive, and done an impressive amount of research, often uncovering little-known facts. Some we didn’t necessarily need to know: “He’d been experimenting with his cooking and had come up with a recipe for sweet buns that he roasted over a low fire until they got crisp. They were wonderful with hot chocolate”.’

(…)

‘Steinbeck married three times. Sounder thinks him something of a cad or misogynist. Well, life is long, people make mistakes, and I would not presume to judge the proper number of marriages or love affairs permitted a man or woman in that lifespan. Souder also does not approve of the “crude” sexual boasting that Steinbeck as a young man wrote in letters to a female confidante. “Why Steinbeck kept telling Beswick things like this can’t be explained in any way that makes it seem okay. It was simply in his nature.” Actually, it’s in the nature of a lot of young people, for whom the acquisition of sexual confidence is often a serious piece of education.’

(…)

‘The last, declining decades are covered dutifully (“The years began to fly away”): lots of drinking, health problems, world travels, the perhaps unmerited Nobel (he himself didn’t think he deserved it), a series of mostly disappointing books and plays (Sea of Cortez, The Moon Is Down, Cannery Row, The Pearl, The Wayward Bus, East of Eden, A Russian Journal, The Winter of Our Discontent, The Short Reign of Pippin IV, Travels with Charley). This last, an amiable excursion purporting to be his report on the real America (ie, not New York) was later outed as mostly a fiction, since he lacked the journalist’s skill set and was too shy to interrogate strangers. He died in 1968, at the fairly young age of sixty-six.’

(…)

‘So we are left to ponder the original question: how major is Steinbeck considered now? But maybe it’s the wrong question: even if we decided he was not that major, we can still read with pleasure a sometimes compelling if minor writer who did his best, and who deserves to have a new biography written about him every forty years – especially at this moment, when he is turning unfashionable and in danger of sliding into that American amnesiac night to which all too many of its worthy writers have been banished.’

Read the review here.

The deadliest conclusions are often the politest ones: compelling but minor.

Probably, it’s slightly better than disappearance into the American amnesiac night, which is needless to say not uniquely American.

The amnesiac night exists everywhere. Sometimes we enter that night without admitting to ourselves. I’ve seen writers disappearing into it with a smile on their face.