On the task of the translator – Dorany Pineda in LA Times:

‘Last month, two of those translators ceased work on the project. — first in the Netherlands, after criticism that a white author had been chosen to translate the work of a Black woman. Dutch translator Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, who last year became the youngest writer to win the International Booker Prize, handed back the assignment. Most recently, Catalan translator Victor Obiols was removed from the job.

“They have told me that I am not suitable to translate it,” Obiols told the Agence France-Presse news agency March 10. “They did not question my abilities, but they were looking for a different profile, which had to be a woman, young, activist and preferably Black.”

Some see the debate over “The Hill We Climb,” out this month in the U.S. and expected to sell millions of copies worldwide, as an opportunity to interrogate literary diversity everywhere. Others say world literature wouldn’t have spread without white translators and ask that we judge the translation, not the translator. Still others worry about the ethics of pressing U.S. notions of race on foreign readers.

Online, the usual battle lines are being drawn. Thomas Chatterton Williams, who tweets frequently about what he considers overreaction on the left, called the change in translators “an international moral panic.” Obiols recently told Spain’s ABCnewspaper that he was “banned.” He suggested that to get another contract, “I will have to look for bitumen,” a material used for blackface.’

(…)

‘The course of that reckoning is familiar: social media backlash leading to institutional reversal. Last month, after the Dutch publishing house Meulenhoff announced Rijneveld as the translator, journalist and activist Janice Deul led social media critics with an opinion piece in de Volkskrant newspaper calling the choice “incomprehensible” and a missed opportunity to hire someone like Gorman — “a spoken word artist, young, a woman and unapologetically Black.”’

(…)

‘Identity is one factor. Lawrence Schimel, an author and translator, brings up a Spanish translation of his own work by a straight man who “made biased, wild assumptions” based on ignorance of gay subculture. “He didn’t know the word ‘leather queen’ and instead of finding out what it meant, he used ‘paganos’ (pagans) because the characters were dressed in leather and engaging in ‘ritual’ activities.” Schimel then offered a counterexample: Another straight man, while translating a story of Schimel’s into German, called a gay sex chat line to ensure that there wasn’t a gay slang term for sex he didn’t know about. “The publisher reimbursed him” for the chat, Schimel said, “since he had put in the legwork to do his job right.”’

(…)

‘Alain Mabanckou, a widely translated French Congolese writer and professor at UCLA, believes that vetting a translator’s national or ethnic origin is a form of “discrimination” and “racism.” “One simply cannot fight against exclusion by reinventing new ways of marginalizing people,” Mabanckou said in an email, “for this would ultimately lead to a situation whereby one could only understand or speak for people who are assumed to be like us.”’

Read the article here.

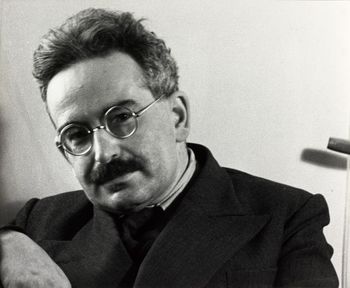

As a friend pointed out, we do need to go back to Walter Benjamin’s ‘The task of the translator’:

This is just the beginning:

‘In the appreciation of a work of art or an art form, consideration of the receiver never proves fruitful. Not only is any reference to a certain public or its representatives misleading, but even the concept of an “ideal” receiver is detrimental in the theoretical consideration of art, since all it posits is the existence and nature of man as such. Art, in the same way, posits man’s physical and spiritual existence, but in none of its works is it concerned with his response. No poem is intended for the reader, no picture for the beholder, no symphony for the listener.

Is a translation meant for readers who do not understand the original? This would seem to explain adequately the divergence of their standing in the realm of art. Moreover, it seems to be the only conceivable reason for saying “the same thing” repeatedly. For what does a literary work “say”? What does it communicate? It “tells very little to those who understand it. Its essential quality is not statement or the imparting of information - hence, something inessential. This is the hallmark of bad translations. But do we not [69] generally regard as the essential substance of a literary work what it contains in addition to information - as even a poor translator will admit - the unfathomable, the mysterious, the “poetic,” something that a translator can reproduce only if he is also a poet? This, actually, is the cause of another characteristic of inferior translation, which consequently we may define as the inaccurate transmission of an inessential content. This will be true whenever a translation undertakes to serve the reader. However, if it were intended for the reader, the same would have to apply to the original. If the original does not exist for the reader’s sake, how could the translation be understood on the basis of this premise?

Translation is a mode. To comprehend it as mode one must go back to the original, for that contains the law governing the translation: its translatability. The question of whether a work is translatable has a dual meaning. Either: Will an adequate translator ever be found among the totality of its readers? Or, more pertinently: Does its nature lend itself to translation and, therefore, in view of the significance of the mode, call for it? In principle, the first question can be decided only contingently; the second, however, apodictically. Only superficial thinking will deny the independent meaning of the latter and declare both questions to be of equal significance . It should be pointed out that certain correlative concepts retain their meaning, and possibly their foremost significance, if they are referred exclusively to man. One might, for example, speak of an unforgettable life or moment even if all men had forgotten it. If the nature of such a life or moment required that it be forgotten, that predicate would not imply a falsehood but merely a claim not fulfilled by men, and probably also a reference to a realm in which it is fulfilled: God’s remembrance. Analogously, the translatability of linguistic creations ought to be considered even if men should prove unable to translate them. Given a strict concept of translation, would they not really be translatable to some degree? The question as to whether the translation of certain linguistic creations is called for ought to be posed in this sense. For this thought [70] is valid here. If translation is a mode, translatability must be an essential feature of certain works.

Translatability is an essential quality of certain works, which is not to say that it is essential that they be translated; it means rather that a specific significance inherent in the original manifest itself in its translatability. It is plausible that no translation, however good it may be, can have any significance as regards the original. Yet, by virtue of its translatability the original is closely connected with the translation; in fact, this connection is all the closer since it is no longer of importance to the original.’

Translation: Harry Zohn.

Read the essay here.

Especially today, we should go back to Walter Benjamin:

‘Not only is any reference to a certain public or its representatives misleading, but even the concept of an “ideal” receiver is detrimental in the theoretical consideration of art, since all it posits is the existence and nature of man as such. Art, in the same way, posits man’s physical and spiritual existence, but in none of its works is it concerned with his response. No poem is intended for the reader, no picture for the beholder, no symphony for the listener.’

I repeat: no poem is intended for the reader.

We should not confuse skill with identity. My identity might primarily consist of being a writer, but I would be absurd to claim: I’m Jewish, unapologetically or apologetically, and for that reason I have the skills of a novelist.

On a sidenote: whatever I am, I am who I am apologetically.