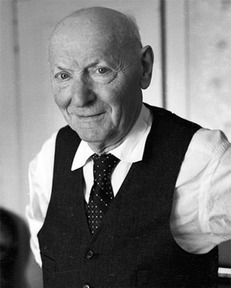

On old news and dark visions – Richard Durgin talked to Isaac Bashevis Singer, the article was published in NYT on Sunday November 26, 1978:

‘W hen 74‐year‐old Isaac Bashevis Singer won the 1978 Nobel Prize in Literature, I visited him in his old‐world apartment on New York's Upper West Side. After receiving constant attention from the world's media, Mr. Singer was exhausted but quietly exuberant. His vivacious wife, Alma, felt that he should rest. But he preferred to talk.

He had received congratulatory telegrams, he said, his blue eyes alight, from Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth. “And you got a beautiful one from Bernard Malamud,” Alma added. “President Carter also telephoned. It was good that I happened to be home on Yom Kippur afternoon,” Isaac Singer said.

Skeptical, subdued and self‐effacing as usual, he voiced one regret: In the flurry of Nobel excitement, his old friends might think he was neglecting them, “… and that hurts me very much.” He was eager to emphasize that awards do not transform either art or the artist. “I will still live at the same address. I will still have the same telephone number. Do you think that winning a prize can change a man's character?”

God forbidl, as one of his fictional characters might say. Like them, Isaac Singer could scarcely be improved upon. Whatever he writes reflects his own humanity and that ineffable inner light which, in our poverty of language, we call spirit. Critics often portray him as a writer of dark visions, yet his deepest vein is richly comic.’

(…)

‘Our final interview took place one evening in September in the Singers’ Surfside, Fla., condominium apartment. Mr. Singer is a vegetarian —“Not for my health,” as he puts it, “but for the health of the chickens.” After dinner, he fell into pensive silence and stared down at the ocean, wrinkled and dark. Never before have I been so deeply aware of being in the presence of a mind consigned to ponder life's mysteries. “What can I do to cheer you up?” I asked. Isaac Bashevis Singer shook his head. “I don't need to be cheered up. I am cheerful enough for a man of my age and my troubles,” he said.’

(…)

‘B: What was the catastrophe that you found here? S: I saw immediately that Yiddish was in a very bad condition. My first impression was that Yiddish was not going to last in America more than another five or six years. In 1935, it was the only language I spoke well, although I knew Hebrew and also some Polish and German. I felt that I had been torn out of my roots and that would never grow any roots in this country. Almost all the young people around me, whomever I met, were Communists. They spoke about Comrade Stalin as if he were not only the Messiah, but the Almighty Himself, and I knew that it was all a big lie. Also I could not make a living here. The Jewish Daily Forward published some of the stories I brought with me, but my desire for writing had evaporated. So was in a very bad state. In Warsaw [I] had women. Here I had difficulties in making acquaintances. The girls all spoke English and those who spoke Yiddish were too old and not exactly to my taste. Sex and Yiddishism don't always go hand in hand, you know. So I was in kind of despair.’

(…)

‘B: How much English did you know when you came here?

S: Nothing. I knew three words: “Take a chair.” But there was only one camping chair in my furnished room and no one visited me there.

B: How did you learn the language? S: I got a teacher. I got a nice girl who taught me English and I also learned some myself. I bought cards and wrote down on each card a word as if would be an author of a dictionary, and every night before I went to sleep I repeated them. And I tried to read the Bible in English.

I would say that after a year I was able to make myself understood. could already buy food in the cafeteria. I could even babble a little English with my teacher. I knew that if I don't learn this language I am lost forever. Immigrants seldom learn English thoroughly — except such men like Nabokov who become professors. Of course, I never intended to write in English. This was the situation.’

(…)

‘B: How do you reconcile these two opposing needs’ S: A man must have some contact with humanity. I would say that the best contact with humanity is through love and sex. Here, really, you learn all about life, because in sex and in love human character is revealed more than anywhere else. Let's say a man can play a very strong man: a big man, dictator. But in sex, he may become reduced to a child or to an imp. The sexual organs are the most sensitive organs of the human being. The eye or the ear seldom sabotage you. An eye will not stop seeing if it doesn't like what it sees, but the penis will stop functioning if he doesn't like what he sees.’

(…)

‘B: In “The Family Moskat” you said. “The Jews are a people who can't sleep themseIves and let nobody else sleep.” Can you define what makes one a Jew?

S: What I meant is that the Jew is such a restless creature that he must always do something, plan something. He is the kind of a man who, no matter how many times he gets disappointed, he immediately makes up some other illusions. It's a special trait of intellectuals. But since the Jews are almost all intellectuals, our restlessness and eagerness to do things, right or wrong, has become almost a national trait.

Here is a story: Once a Jewish man went to Vilna and he came back and said to his friend, “The Jews of Vilna are remarkable people. I saw a Jew who studies all day long the Talmud. 1 saw a Jew who all day long was scheming how to get rich. I saw a Jew who's all the time waving the red flag calling for revolution. saw a Jew who was running after every woman. I saw a Jew who was an ascetic and avoided women.” The other man said, “I don't know why you're so astonished. Vilna is a big city, and there are many Jews, all types.” “No,” said the first man, “it was the same Jew.” And in a way there is some truth in this story. The intellectual Jew is so restless that he is almost everything.’

(…)

‘ … you know the liberated woman suspects everybody. Like a Jew who calls every gentile an anti-Semite, the liberated woman suspects almost every man of being an antifeminist. They would like writers to write that every woman is a saint and a sage and every man is a beast and an exploiter. But the moment a thing becomes an “ism,” it is already false and often ridiculous.’

(…)

‘The writers of the 19th century knew that the real gold mine of literature is not in brooding about yourself so much as in observing other people. There's not a single story by Chekhov, for example, where he wrote about himself. Although I do write from time to time in the first person, I don't consider it a real healthy habit. I'm against the stream of consciousness because it means always babbling about oneself. When you meet a man and he talks only about himself, you're bored stiff. The same thing is true in literature. When the writer becomes the center of his attention, he becomes a nudnik. And a nudnik who believes he's profound is even worse B: What about the so‐culled stream‐of‐consciousness technique as used by Faulkner and Joyce, in which there is more than one narrator? S: I don't think that they made really great stories. The bitter truth is that we know what a person thinks not when he tells us what he thinks, but by his actions, This reminds me: Once a boy came over to the cheder where I studied, and he said “Do you know that my father wanted to box my ears?” So the teacher said, “How do you know that he wanted to box your ears?” And the boy said, “He did it.” A man may sit for hours and talk to you about what he thinks. But what he really is, you can judge best by what he did. This is a real heresy to the psychology and the psychiatry of our time — everything is measured by your thoughts and by your moods.’

(…)

‘If you write that a man came home to his wife, he found her [and her] lover in her bed and he shot both of them, the reader understands more or less how angry he was, and what he was thinking when he was arrested. Real literature concentrates on deeds and situations. The stream of consciousness becomes very soon obvious. Tolstoy describes sometimes what his heroes were thinking in their hearts and Dostoyevsky does this in a big way. Nevertheless, their works are full of action. When you read “Crime and Punishment,” you don't know until the very last page why Raskolnikov did what he did.’

(…)

‘“What does it mean, a Yiddish writer? What kind of career can a Yiddish writer make? And what is the sense of writing in a language which is dying and for people who are backward?” But I felt — and [I] am not boasting. I just say so ‐ that Yiddish and the Jewish people and their language were [for] me [the] most important things. I felt that if I want to be a real writer, I have to write about them and not about the American gentiles.”’

(…)

‘Can you sum up your conditions for writing?

S: First I get the idea, the emotion. Then I need a plot: a story with a beginning, a middle and an end; just as Aristotle said it should be. A story to me means a plot where there is some surprise. It should be so that when you read the first page, you don't know what the second will be. When you read the second page you don't know what the third will be. Because this is how life is full of surprises. There is no reason why literature shouldn't have many surprises as well.

The second condition is I must have a passion to write the story. Sometimes I have a very good plot but somehow the passion to write this story is missing. If this is the case, I would not write it.

And the third condition is the most important: I must be convinced, or at least have the illusion, that I am the only one who could write this particular story or this particular novel. This does not mean that I am the best writer. That fur this particular topic and environment I am the only one. Let's take for example, “Gimpel the Fool.” The way I tell it, is a story which only I could write — not my colleagues or, say, writers who were brought up in English.

Now, for a plot you need characters. So instead of inventing characters, I look at the people I have met in my life who would fit into this story. I take ready‐made characters. This does not mean that I just “photograph” them. No. I sometimes combine two characters and make from them one character. I may take a person whom I met in this country and put him in Poland or vice versa. But just the same, I must have a living model.

The fact is that painters, all great painters, painted from models. They knew that nature has more surprises than our imagination can ever invent.’

(…)

‘I think it's a great. tragedy that literature stopped looking at models. Writers are so interested in “isms,” in ideologies and in theories, that they think the model cannot add much. But actually, all the theories and all the ideas become stale in no time, while what nature delivers to us is never stale. Because what nature creates has eternity in it.’

Read the article here.

This is one of the funniest and most honest and less pretentious interviews with authors I’ve read.

I don’t necessarily agree with all what is being said here.

But Singer's defense of the 19th century novel, his description of men’s urgent needs and desires – and the fact that these needs and desires are the novelist’s most natural material – his hesitance to connect literature to politics, his emphasis on action, that’s all even more refreshing in 2021 than it was in 1978.

And yes, all artists are in need of a model. (Which is not the same as a muse, don’t get me wrong.) Of course a model can be a pair of sun glasses, but in the long term a human being is more interesting than his sun glasses.