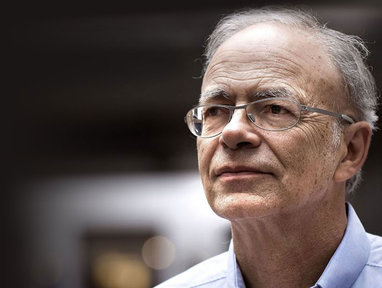

On giving offense and sainthood – Daniel A. Gross interviewing Peter Singer in The New Yorker:

‘Singer calls himself a consequentialist: he believes that actions should be judged by their consequences. His ideas about our ethical obligation to help people in extreme poverty, first expressed in his essay “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” from 1972, and later in his book “The Life You Can Save,” from 2009, are foundational to the effective-altruism movement, which encourages people in wealthy countries to donate large sums to charities that measurably improve the most lives. They have also influenced the Giving Pledge, a philanthropic campaign launched by Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates.

Others have discovered Singer’s work because of the controversies he has ignited. In his book “Practical Ethics,” from 1979, he argued that parents should have the right to end the lives of newborns with severe disabilities. In the decades since, a number of his lectures have been disrupted by demonstrators or cancelled altogether. In 1999, the disability-rights group Not Dead Yet protested his appointment at Princeton, where he still teaches. That year, he was profiled in this magazine by Michael Specter; the piece was titled “The Dangerous Philosopher.” On Friday, Singer and two fellow-ethicists launched a peer-reviewed publication called the Journal of Controversial Ideas.’

(…)

‘You seem to be a skeptic of Marx’s ideas in practice. Why did you write a book about Marx? I was invited to do a book for an Oxford series. I had studied Marx when I was a graduate student, and there was this view of early Marx, largely based on some unpublished writings, that was all about alienation, and that there was a decisive break that came somewhere around 1848—first you had the kind of Hegelian-philosophy Marx, and then you had the different, scientific Marxism, and there wasn’t much of a connection between the two. In studying this, I’d been persuaded that was wrong, that there was continuity, and that you could explain what Marx was on about in his later writings by looking at the early writings—and that this also explained some of the flaws in Marx’s thinking. The idea that history is leading toward this goal, where all the contradictions will be resolved, came straight from Hegel. I think there are some interesting critiques of what’s going on in capitalist societies, but he really thinks that the revolution is inevitable. I think that was clearly wrong.

(…)

‘It seems to me that the movement that has grown up around your philosophical work has ended up being very compatible with capitalism, in the sense that some of its practitioners are people who set out to earn a lot of money—some of them are billionaires who have decided to give away the money that they’ve amassed. Was that something you expected, for capitalism to almost be incorporated into your philosophical work?

I don’t think capitalism is incorporated into my philosophical work. I think my philosophical work is neutral about what is the best economic system—but it’s also realistic, and I think we’re stuck with capitalism for the foreseeable future. We are going to continue to have billionaires, and it’s much better that we have billionaires like Bill and Melinda Gates or Warren Buffett, who give away most of their fortune thoughtfully and in ways that are highly effective, than billionaires who just build themselves bigger and bigger yachts.

Does that mean you’re not that interested in the question of whether billionaires should exist?

Look, I think it would be better if you had an economic system in which we didn’t have billionaires—but the productivity that billionaires have generated was still there, and that money was more equitably distributed. But, really, there hasn’t been a system that has had equity in its distribution and the productivity that capitalism has had. I don’t see that happening anytime soon. If one country starts to tax billionaires so that there can’t be any billionaires, those billionaires are going to go to other countries where they can continue to be billionaires.’

(…)

‘The bias that you described—the assumption that a person with a disability is worse off—is that something that you recognized in yourself as these conversations were happening?

To some extent, yeah, I think so. I thought Harriet was a very good example of somebody who lived a rich and fulfilling life despite a severe disability. No intellectual disability in her case, of course. She was very sharp.

Did she change your mind in some way?

Maybe a bit. Maybe a bit.

Tell me about the Journal of Controversial Ideas.

This is a response to what I feel is a worrying trend of restricting freedom of thought and discussion, including in academic life. Francesca Minerva, Jeff McMahan, and I decided to create a journal that would, first, be prepared to publish controversial ideas and not retract articles because there were petitions or letters signed against them, and second, to allow articles to be published under a pseudonym—which, as far as we’re aware, no peer-reviewed academic journal does.’

(…)

‘Could you tell me about some of the topics that are appearing in the first issue? Not surprisingly, perhaps, the first issue has a couple of papers on gender issues. Does the term “woman” mean adult human female? And does that suggest that there’s a biological component to it rather than simply a matter of gender preference? Are those papers in opposition to one another? Yes, they are. We have another interesting paper called “Cognitive Creationism,” which explores parallels between young-Earth creationism and the ideological views that reject well-established facts in genetics, particularly related to differences in cognitive abilities—across individuals, not between demographic groups. There’s a paper discussing blackface in terms of various cultural traditions, whether blackface can be acceptable. There’s a defense of direct action to stop animal abuse. There’s a paper raising the question of whether despotism is necessary to stop climate change. There’s a paper about punishment, which contemplates enforced coma as an alternative to long-term imprisonment.’

(…)

‘My perception is that there are times when freedom-of-speech arguments provide cover to ideas that inflict harm—and that some of these arguments come from thinkers who already do have the freedom to express their views, as long as they’re willing to be held accountable for them in a public forum.

The journal is particularly aimed at protecting junior academics who don’t have tenure. But if the concern is just that people write them hate mail, I don’t see that as an issue. Freedom of speech applies to people who write hostile criticism on Twitter—they have freedom of speech, too. I think you’ve just got to develop a thick skin. But if no publisher will touch them for fear of being branded, then I think you have a problem. John Stuart Mill says this explicitly: offense can’t be a grounds for prohibiting free speech, because it’s just too wide.’

(…)

‘If, through truth-seeking, you conclude that the person’s argument has an oppressive effect, what comes next? If it turns out that an argument published in the Journal of Controversial Ideas causes more harm than good, what comes next? That is quite possible—that an individual argument might cause more harm than good. What I and my co-editors believe is that promoting freedom of thought and discussion, on the whole, will do more good than harm, even if occasionally an individual article does cause more harm than good.’

(…)

‘Do you think of yourself as a good person? Yes, because that invites a comparison with other people, and I think by those standards I’m a good person. But do I think of myself as an ideally good, perfect person, the perfect person, a secular saint? Definitely not.’

Read the interview here.

A peer-reviewed Journal of Controversial ideas seems to me an excellent idea, even when the title of a the journal is bit awkward. What’s controversial or not is not for the author of publisher to decide.

Promoting freedom of thought will do more good than harm. Yes. Which of course doesn’t mean that all thought or essays are equally valuable, hence peer review.

The widespread idea that silencing the socially undesirable person or the person with socially undesirable ideas is a virtue is just plainly wrong.

Needless to say, the fact that something is socially undesirable doesn’t make it interesting or significant.

Some people might take offense when a certain text or opinion is published but that is not reason enough to not publish this text.

An author might be extremely offended when a negative review of his poetry is published, but that is not reason enough to not publish the review, even when the review is biased or unjust.

Underneath all this is the confusion about the transgression and the punishment.

Reasonable people can conclude that a certain person misbehaved, that his actions are morally wrong, but these people might still reach the conclusion that it’s better to not punish the transgressor.

The addiction to punishment is one of the illnesses of mankind.