On American wars – Alice Kelly in TLS:

‘War is one of the founding principles of the United States of America, and has been a constant of its history. It would be feasible to tell the story of the US entirely through the lens of conflict, beginning with the wars to take land for settlement from the native peoples, continuing through the War of Independence, the Civil War, both World Wars, the Korean War, Vietnam and the ongoing “Forever Wars”, to name only the most prominent. This is a country of “wartime presidents”, and one that venerates its veterans (“Thank you for your service”). War permeates the arts in the US, too, creating what is arguably the most militarized civilian culture in the world. Even Snoopy harbours a fighter pilot alter ego.’

(…)

‘War and American Literature, edited by Jennifer Haytock, is a diverse volume that runs from the Revolutionary War up to the present day. It analyses war literature through themes including propaganda, injury, memorialization, cultural change, patriotism, queerness, ecocriticism and whiteness. Michael Zeitlin’s essay on “Bodies, Injuries and Medicine” considers how medical memoirs from America’s wars in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan can “help us see inside the caskets” that are flown home, comparing, for example, classic war fiction with contemporary medical textbooks and the accounts of “Mortuary Affairs” processors in the Iraq War.’

(…)

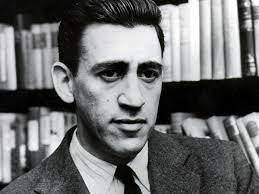

‘There are also suggestive readings of works we might not expect. Philip Beidler considers J. D. Salinger as a Second World War combat writer, noting that “the troubled, disaffected, lonely teenaged Holden Caulfield manifests significant symptoms of PTSD”. Likewise, Trout’s chapter examines cultural memory and memorialization in books from Herman Melville’s Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866) to Ernest Hemingway’s retrospective narrative Across the River and into the Trees (1950).’

(…)

‘As the editors and contributors of this admirable volume note, however, the First World War not only had important sociopolitical consequences for the trajectory of the United States in the twentieth century, but was hugely important in cultural terms, too. Scott D. Emmert in his chapter on fiction claims that rather than being a forgotten war, this conflict “was and remains a complex, contradictory, and vital event still shaping our understanding of who Americans were and who they may become” – in literature, at least.

This volume goes beyond the typical Lost Generation roster of Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, E. E. Cummings et al. In a field of scholarship that is relatively new, Tim Dayton and Mark W. Van Wienen’s introduction helpfully summarizes the development of both literary and historical scholarship of the war: “only in the 1990s did literary critics and cultural historians refocus attention on the American literature of the war, exploring writing that lies outside the disillusionment narrative” (ie, the formerly dominant view regarding a loss of faith in the ideals with which Americans had gone to war). The existing scholarship constitutes a much smaller field than that of other national war literatures – but this volume significantly recognizes the study of American First World War literature and culture as a transformative, if diverse, field in its own right.’

(…)

‘A History of American Literature and Culture of the First World War makes claims for the originary nature of much of this material. Pearl James, for example, argues that “the war helped to usher in a new era of image ubiquity that never went away”. We are left in no doubt of the indelible mark left on literary and cultural development by American involvement in the First World War, and the key role that literature and culture played in selling, mediating and remembering the war to the American people. In doing so, the authors reclaim the place of America’s forgotten war in the long chain of conflicts of this uniquely military nation.’

Read the article here.

A uniquely military nation? Maybe. In the summer of 2015, I traveled through Russia by car, from the border with Belarus to the border with Kazakhstan. In the city of Volgograd (former Stalingrad) I was impressed and slightly unsettled by the war museum, all about the Battle of Stalingrad, and how people in Volgograd talked about battle and the war (Great Patriotic War i.e. World War II) - as if it all happened yesterday.

All empires and would-be empires are uniquely military nations. Only after the demise of the empire, soccer becomes more important than the army.

And Holden Caulfield suffering from PTSD, because Salinger had been a comat soldier, is not so much insightful – it’s a loss.

Life and literature become a quest for symptoms and deviations from this thing called normality.