On a love-triangle – Frances Wilson in TLS:

‘Spellbound by Marcel is described as a group biography of Marcel Duchamp, Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood, but it is fairer to call it a Cubist take on a triangle. In the summer of 1917, when both were in love with the elusive Duchamp, Roché, the author of Jules et Jim, and Wood, the Mama of Dada, had a brief liaison. What happened between them was momentous to Wood, irrelevant to Roché and a relief to Duchamp. The affair overlapped with their shared editorship of the Dadaist journals, The Blind Man and Rongwrong, and the decision by the Society of Independent Artists to reject from their inaugural exhibition Duchamp’s “Fountain”, a standard urinal purchased at the J. L. Mott Iron Works store in Manhattan and signed “R. Mutt, 1917”.’

(…)

‘Roché, a Parisian with taste but no talent, found his forte as a social facilitator. Having introduced Picasso to Gertrude Stein, he encouraged Cocteau to collaborate with Picasso and Erik Satie to produce the ballet Parade. In New York, where he arrived in November 1916, it was his sexual agility that got him noticed. The ménage à trois in Jules et Jim (1953), written in his seventies and transformed by François Truffaut from a pedestrian novel into a masterpiece of New Wave cinema, is not specifically a description of Duchamp, Wood and Roché, because all Roché’s relationships were triangular.

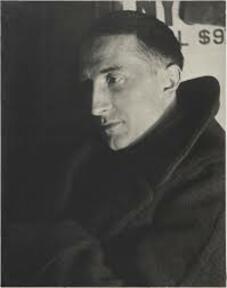

In the autumn of 1916, when Brandon’s story begins, Wood is a twenty-three-year-old actress, full of “American snap”, and Roché a thirty-seven-year-old lothario who refers to his penis as “God”, and the twenty-nine-year-old Duchamp, newly arrived in Manhattan having had his work rejected in Paris, is enjoying the notoriety generated by his “Nude Descending a Staircase”, exhibited at the Armory Show in 1913. The canvas, which demonstrated, as Duchamp said, “the problem of motion in painting”, was seen by the New York Times as “an explosion in a shingle factory”.’

(…)

‘Wood’s diaries suggest that Duchamp introduced her to Roché in February 1917, and Pour Toi suggests that the affair with Roché began the following April, when it became clear that Duchamp was not interested in her. By the time she wrote I Shock Myself, however, Wood remembered things differently, which is perhaps not surprising given that it was seven decades later. “Marcel knew I was in love with his good friend Roché and did not approach me amorously. Secretly I wished he would. My love for Roché could not keep me from being a little in love with Marcel.” Roché, meanwhile, also kept diaries (a list of sexual conquests written in a hodgepodge of French and English), which Brandon reads against his self-serving, unfinished autobiographical novelVictor (the name bestowed on Duchamp, victor of all he surveyed). According to Roché, Duchamp threw Beatrice into his arms in order to get her off his hands. Roché was happy to add her to his harem, which included another of Duchamp’s lovers, Louise Norton, Duchamp’s patron Lou Arensberg, and Wood’s best friend, Alissa. “Whole situation with Marcel is normal”, Beatrice reassured herself in her diary. “My emotions are bound to shudder, My spine cold and hot. Marcel like a knife, but he is right.”’

(…)

‘Duchamp was spellbinding because he was unreadable; both Roché and Wood describe his face as a mask. “My irony comes from indifference”, he told Roché. “It’s meta-irony”. What, then, was Roché’s secret? He was a surrogate Duchamp whose hobby was re-reading his collection of love letters, and his spell soon wore off. The character of Wood is the more interesting puzzle, and it is to Brandon’s credit that she does not try to solve it.

Spellbound by Marcel is both novel and incomplete. The French is sometimes translated, sometimes not; the author sometimes explains Duchamp’s word plays, sometimes not; sometimes, but not always, she tells us in a footnote the source of a quotation. There are no endnotes. To get the best from the book, it should be read alongside Wood’s diaries, which are available online, and I Shock Myself. Duchamp’s record of his life can be found, says Ruth Brandon, in his art, in which case his comments on the summer of 1917 can be found in “Fountain”.’

Read the article here.

Duchamp’s irony might come from indifference, there is another kind of irony to be found in this review.

Roché was probably a minor writer, but his ‘pedestrian’ novel gave us a indispensable movie. And the fact that all his relationships were triangular points to a talent as well. Although I would not recommend confusing your genitals with God. Don’t give names to your genitals in general.

And now let’s watch ‘Jules et Jim’ again.