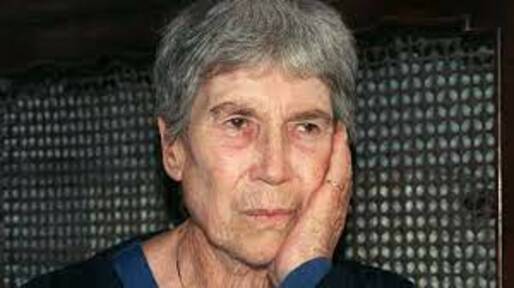

On Natalia Ginzburg – Lara Feigel in The Guardian (in 2019):

‘Thus began a 50-year writing career. Ginzburg was influenced by Pavese and was later happy to describe herself as a neorealist, part of a literary movement that echoed contemporary Italian cinema. She looked back on neorealism as “a way of getting close to life, of getting inside life, inside reality”. But her voice was distinctive from the start: cold in its exposure of false sentiment while warmly attentive to the details of family life and female experience.’

(…)

‘The collection ends with two masterpieces that push out into a larger moral landscape. The first, Human Relationships leads movingly through the stages of life from childhood to adulthood. Ginzburg writes, unusually but absolutely assuredly, in the first person plural, recounting “our” rebellion against our parents, our search for the right friend and the right lover, moving onwards into motherhood and war. The whole of life is here, but perfectly scaled down to focus on the everyday, with its slammed doors and exercise books (best friends briefly with a popular girl, she examines her precious book with its “beautiful angular handwriting in blue ink”). Along the way, she asks fundamental questions about how we can be moral beings who love our children, our friends and neighbours and at the same time serve a higher purpose (at once God and a communist vision of the collective). The shock of motherhood, then as now, is in its selfishness: “We love our children in such a painful, frightening way that it seems to us we have never had any other neighbour … Where is God now? We only remember to talk to God when our baby is ill.” This is changed by war, when she learns to ask for help from passersby. For a while, she renounces possession of things and people, growing up in the process. “We are adult because we have behind us the silent presence of the dead, whom we ask to judge our current actions and from whom we ask forgiveness for past offences.”’

(…)

‘This takes us back to the dilemmas described in Human Relationships and forwards to those in Family Lexicon. They are dilemmas faced also by Calvino and Pavese (whose suicide haunted Ginzburg as it haunted Calvino) and confronting us in only subtly mutated forms today. How to keep the energy and excitement of the postwar world generative rather than merely intoxicating; how to build a new world with integrity; how to live as an individual authentically within a community; how to survive the judgment of the silent dead.’

Read the article here.

I read Pavese when I was 19. I didn’t understand everything, but the darkness remained attractive, to this day.

A few years later my editor at a Dutch newspaper asked me to write something about Natalia Ginzburg. I appreciated her work, but it was only recent that I read a few of her essays that I had missed in 1998, or maybe my memory wasn’t up to the task.

Human relationships is a funny, unsentimental and uplifting piece about all the stages we go through in life. Uniqueness, if does exist, can be found in the corners of our living rooms and our kitchens, just a few crumbs. Yes, Ginzburg is one of the most unsentimental writers I know.

‘We only remember to talk to God when our baby is ill.’ God as a last resort. It sounds like a shameful act.

I believe that it was Primo Levi who wrote that for non-believers talking to God in moments of utter despair was like cheating.

But Levi was more of an atheist than Ginzburg, I assume.